Why the deaths of Latinos at the hands of police haven’t drawn as much attention

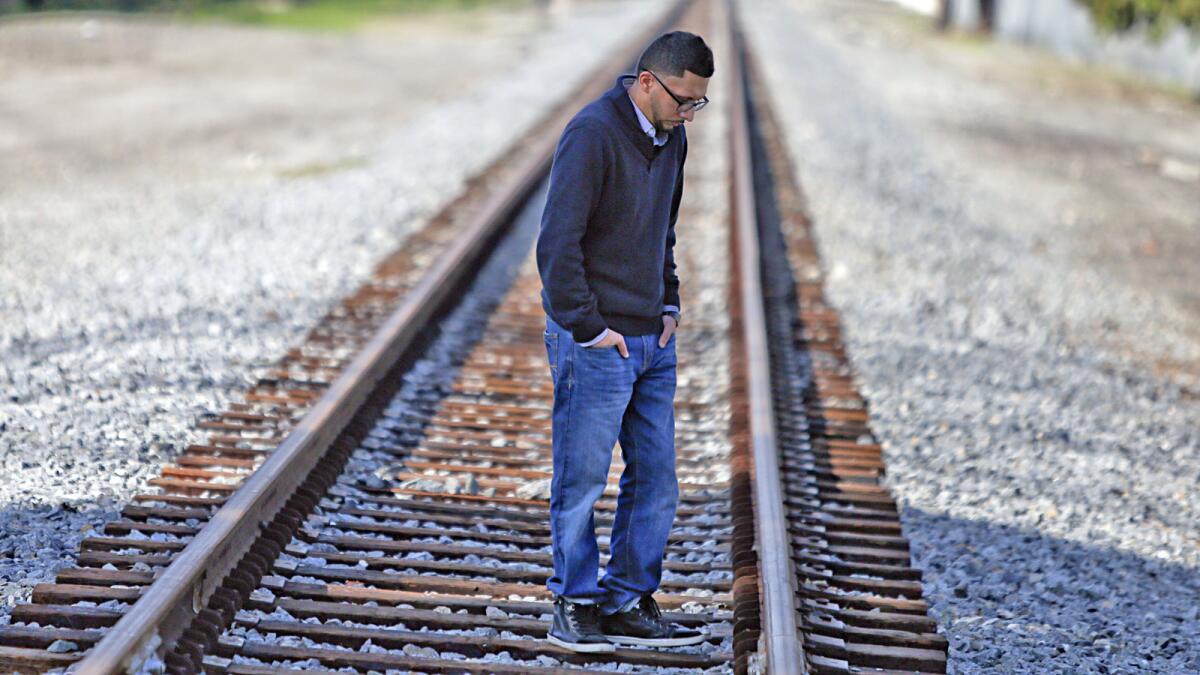

Kris Ramiriez stands on the railroad tracks in Paramount near where his brother, Oscar Ramirez, was killed by deputies in October.

- Share via

Kris Ramirez never saw police as a threat. Growing up, his body didn’t tense with us-versus-them dread when police cruisers drove through his Southeast Los Angeles neighborhood.

“If someone is wearing a uniform,” Ramirez said, “you show respect.”

Then last year, four days before Halloween, a Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy shot and killed his brother, Oscar Jr., along railroad tracks near Paramount High School. Deputies said the 28-year-old didn’t comply with orders and moved his arm in “a threatening manner.” Ramirez was unarmed.

The Ramirez family marched in front of the Paramount sheriff’s station and held vigils, but they struggled to find wider support for their cause. As the family grieved, the national Black Lives Matter movement picked up energy, bolstered locally by the fatal shooting of Ezell Ford, a mentally disabled black man, by LAPD officers.

Watching the protests over Ford’s killing, Kris Ramirez felt frustrated: “Why can’t we get that same type of coverage or help?”

The muted reaction to the deaths of Latinos in confrontations with police tells a larger story: Black Lives Matter is starkly different from Brown Lives Matter. In contrast to the fatal shootings of African Americans such as Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., and Walter Scott in South Carolina, deaths of Latinos at the hands of law enforcement haven’t drawn nearly as much attention.

A federal judge on Tuesday ordered the release of a video showing Gardena police officers shooting two men, killing Ricardo Diaz Zeferino, an unarmed Latino. The video has been viewed millions of times on YouTube. It generated national media coverage, but very little protest.

Over the last five years in L.A. County, coroner’s data show that Latinos, who make up about half of the county’s population, also represent about half the people killed by police. Of the 23 people fatally shot by law enforcement in the county this year, 14 were Latino.

The disparity is rooted, at least in part, in historical context. No group in America has had an experience with police more fraught with institutionalized brutality than the black community. Police shootings of African Americans, men in particular, outweigh those of any other group in L.A. County. Although they make up only 9% of the population, since 2000, on average, blacks have represented 26% of those killed by police.

Despite overlap on some social justice issues, many differences shape the Latino and black experiences with law enforcement in the U.S.

In Southern California, Latinos are a large and visible part of law enforcement. Within the LAPD, the state’s largest city police department, 45% of officers are Latino. (Blacks make up about 11% of LAPD’s officers.) In the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department, Latinos represent 43% of the ranks.

In the overwhelmingly Latino neighborhoods of L.A.’s Eastside patrolled by the LAPD’s Hollenbeck division, many of the cops are “homegrown officers” raised in the surrounding neighborhoods, said Capt. Martin Baeza. The station is routinely among the most coveted spots in the department. Baeza said that the last time he checked, there were about 70 officers waiting to be transferred to the division.

While the greater Eastside has a history of protests and activism, including criticism of law enforcement, support for police is strong — one of the major draws for officers, Baeza said.

And historically, the image of Latinos protesting is linked to immigration, not police brutality, said Amin David, 82, former president of a Latino civil rights group, Los Amigos of Orange County.

“Immigration occupies a big part of our table,” David said. “It squeezes out the police component.”

Latinos have had some storied periods of tension with law enforcement in Los Angeles. Three people, including Times columnist Ruben Salazar, died in 1970 when police and protesters clashed during an anti-Vietnam War protest organized by Latinos in East L.A. And tensions ran high for decades in certain neighborhoods, such as the once gang-heavy Ramona Gardens housing project, where police and some residents clashed, especially after officer-involved shootings.

The last very large public outcry happened three years ago in Anaheim, where two deadly police shootings triggered several days of unrest.

Cultural and historical differences aside, David said he thinks black churches have played a large role in capturing attention for the Black Lives Matter movement. In Catholic congregations like David’s own, he said, priests don’t talk about police killing Latinos.

“I really applaud the African American churches,” David said. “They really know the buttons to press.”

As a parent, Yolanda Dominguez told her son to get good grades, obey traffic laws and avoid gangs. But when it came to dealing with law enforcement, the 39-year-old Hawthorne resident had no special advice for him.

“My message has always been don’t get involved in anything bad and that will limit your interaction with police,” said Dominguez, who came to the United States from Mexico in the mid-1990s. “It’s not the police’s motive to kill people anyway.... I never had this conversation with my son because the important issue was working and his schooling.”

Dominguez, who owns the Dominguez Tire shop in Gardena, said she regarded police in the U.S. positively, especially compared to those in her native Mexico.

“Over there the police are always asking for bribes,” she said. “Here they try to help.”

Jose Viramontes, 39, a tire shop employee, said he never talked to his son and five daughters about how to deal with police. On the list of things to worry might happen to your children, getting shot by a cop didn’t register. If he ever did mention it, he said, it was only because of what police interactions implied: That they might have gotten in trouble.

He said his 16-year-old daughter told him about the video of the Gardena shooting. “She told me, ‘Dad, police shot another Latino,’” Viramontes recalled. “My wife told her, ‘See, this is why you listen to the police.’”

Luis Carrillo, an attorney who has represented Latino families in use-of-force cases, said that because of a history of oppression in Latin America and a streak of Catholic conservatism, many Latinos have a built-in wariness of police agencies and adhere to a “don’t rock the boat” mentality. That mind-your-own business approach within the community can leave families of people killed by law enforcement feeling isolated.

It’s a feeling Kris Ramirez knows well — one he said he still struggles with. He said he still sees reminders of his younger brother everywhere.

In the moments leading up to the October shooting, a 12-year-old student from a nearby school told her mother that she had seen two men armed with a knife and handgun. Oscar Ramirez, a fit, 6-foot-tall Latino, matched the suspects’ description. Authorities say he fled when they tried to question him.

The family disputes the official account, saying Oscar Ramirez never posed any threat to the deputies and that four or five bullets struck him in the back. They filed a federal wrongful-death lawsuit against the Sheriff’s Department in April.

Ramirez fears his brother’s memory will be lost in the court process. But he will live on in the minds of his family.

On what would have been Oscar’s 29th birthday in June, his father planted a tree near the train tracks.

Hoy: Léa esta historia en español

Times staff writers Javier Panzar, Kate Mather and Angel Jennings contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.