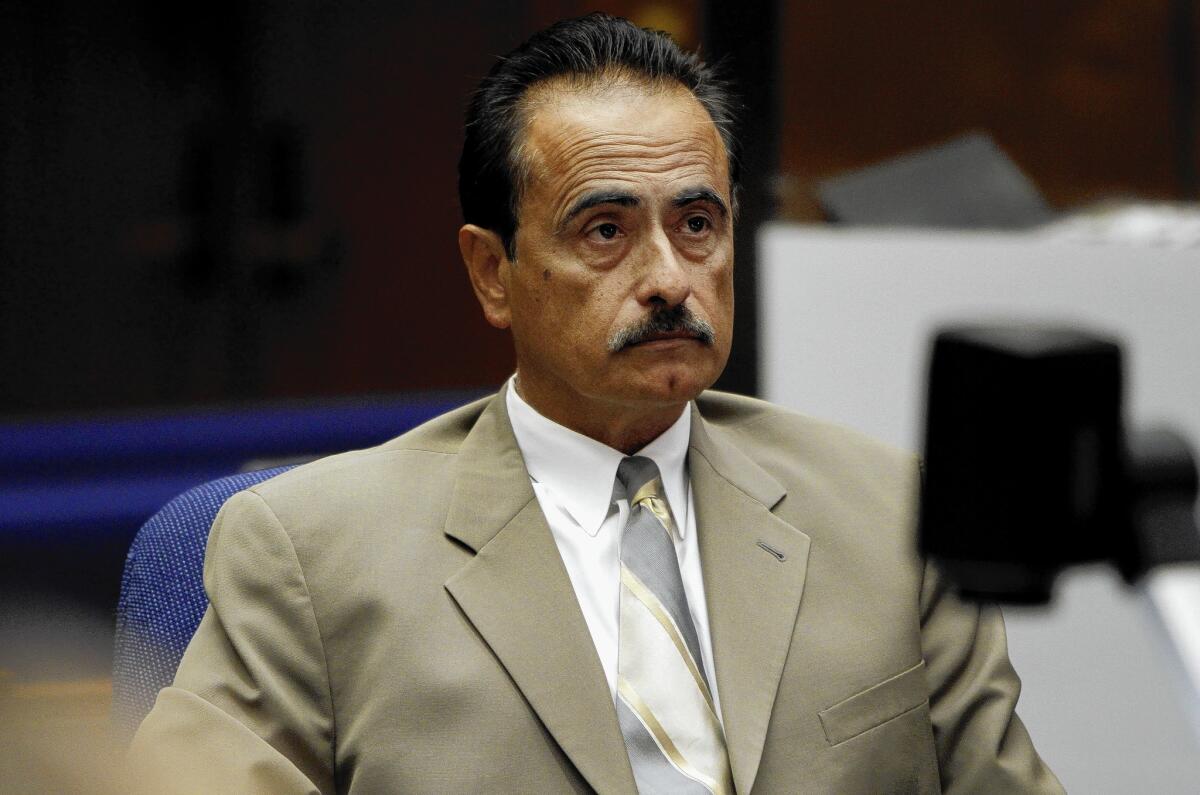

Richard Alarcon’s perjury and voter fraud trial to resume this week

- Share via

In his ongoing perjury and voter fraud trial, former Los Angeles Councilman Richard Alarcon is seeking to fend off two intertwined lines of attack by prosecutors: that he allegedly lived illegally outside his district and was a career politician who put personal ambition first.

Alarcon’s attorneys have mounted a pointed defense to accusations that the veteran politician and his wife, Flora Montes de Oca Alarcon, lied about where they lived so Alarcon could run in the city’s San Fernando Valley 7th District, which he represented until last year.

They say the Alarcons were away from their home because of renovations but always planned to return. And they argue that state law doesn’t specify, for election purposes, how much time a candidate must spend at his official residence or how long he can be absent.

But the prosecution is making a parallel argument that some experts say could affect the jury’s decision: that Alarcon’s desire to extend his career motivated him to intentionally deceive the public.

In the first thrust of her opening statements, Deputy Dist. Atty. Michele Gilmer portrayed Alarcon, 60, as a “career politician” who was seeking to jump from office to office. She noted that after Alarcon, a Democrat, won a seat in the California Assembly in November 2006, he immediately began his campaign for an L.A. City Council seat, which had been left vacant in the same election.

In such perjury and fraud cases, there tends to be less physical evidence to convince the jury beyond a reasonable doubt, said Richard Hasen, a UC Irvine law professor specializing in election law. “It’s going to be much mushier than that,” Hasen said, with prosecutors trying to get “into the mind” of Alarcon.

Jessica Levinson, a professor at Loyola Law School who studies election laws, said the prosecution wants the jury to conclude that “the Alarcons knew exactly what they were doing.”

Together, the Alarcons face 22 felony counts in connection with allegedly falsely claiming they lived in Panorama City in campaign, voter registration and Department of Motor Vehicles documents between 2006 and 2009. If convicted on all counts, Alarcon could face up to five years and his wife up to four years in county jail, the district attorney’s office said.

The trial began last month and resumes Monday. Gilmer opened her case by arguing that Alarcon made the decision to immediately pursue a City Council seat after winning his Assembly seat because voters passed a city charter amendment that November that increased the length of time council members can remain in office.

To support that point, Gilmer called as an early witness a top former Alarcon aide, who confirmed that his boss could have stayed in office longer as a councilman. But, the aide stressed the additional time amounted to just several months.

Three days after Alarcon won his state position, he registered to vote in Panorama City in the council’s northeast Valley 7th District. The city charter requires candidates to reside in the district they seek to represent.

Prosecutors say Alarcon, while running for council, actually lived in a bigger home in Sun Valley outside the 7th District. The defense argues that the Alarcons’ permanent residence was the Panorama City home but the couple wasn’t always living there because they were renovating the residence in anticipation of the birth of their daughter in 2008.

A key point of contention is how state residency rules apply to the case. California law says a candidate can have only one “domicile,” where “habitation is fixed” and he or she plans to remain and make a permanent residence.

The prosecution emphasizes the first requirement, asserting that the Alarcons never actually lived in the 7th District and the Panorama City house was just “a trick to the eyes.” The Alarcons’ attorneys have focused on the second requirement of the residency law, saying the couple always intended to return to the Panorama City home and were officially domiciled there.

Hasen, the UC Irvine professor, said proving where someone was domiciled can be difficult because it essentially comes down to the mental state of the candidate: Where did he or she intend to make a permanent residence?

Hasen questioned how much weight jurors might give to the prosecution’s argument that Alarcon was motivated to break the law because he wanted to remain in office longer.

“That’s the motive of essentially every politician,” he said. “That doesn’t necessarily prove that there was an intent to deceive.”

But Levinson, a Los Angeles Ethics Commission member, said that highlighting Alarcon’s alleged political calculations could spell trouble for the defense.

Alarcon’s attorney Richard Lasting has focused heavily on the residency requirements. He began his opening statements by telling jurors: “The central issue in this case is the issue of domicile.” The defense has presented photos they say show that renovations were being made between 2006 and 2009, when Alarcon was twice a City Council candidate. They include, among other things, before and after images showing that the exterior was painted.

Stephen Folden, who has lived across the street from the Alarcon’s Panorama City house for 40 years, testified that he thought the residence was empty in that period. Aza Zapasov, who runs a day-care center next to the home, also testified that it appeared no one lived there.

But under questioning from the defense, Zapasov also acknowledged that the Alarcons came by her day-care center in June 2009 to discuss whether their baby was old enough to enroll, implying they planned to settle in the neighborhood. Zapasov also said she saw Montes de Oca Alarcon outside the house with a stroller on one or two occasions.

The prosecution continues to push a portrayal of Alarcon as a politician who understood the rules and knowingly broke them.

Early in the trial, Carolyn Jackson, who worked with city lawmakers as a representative of the city Department of Transportation before retiring in 2010, testified that she met with Alarcon in May 2007, two months after he was elected to the council.

She said when she congratulated him, Alarcon told her: “You know, I wasn’t even living in the district when I was elected.” Jackson said he added: “I am now, of course.”

Jackson said she was surprised and “pretty angry,” because “it’s illegal to run in a district you don’t live in.” Alarcon’s attorney sought to undercut Jackson’s testimony by pointing to discrepancies in her recollection of details of the conversation in her testimony before a grand jury, at the preliminary hearing and during this trial.

The trial is expected to continue for about two weeks.

soumya.karlamangla@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.