L.A. County jails to expand immigration screening

- Share via

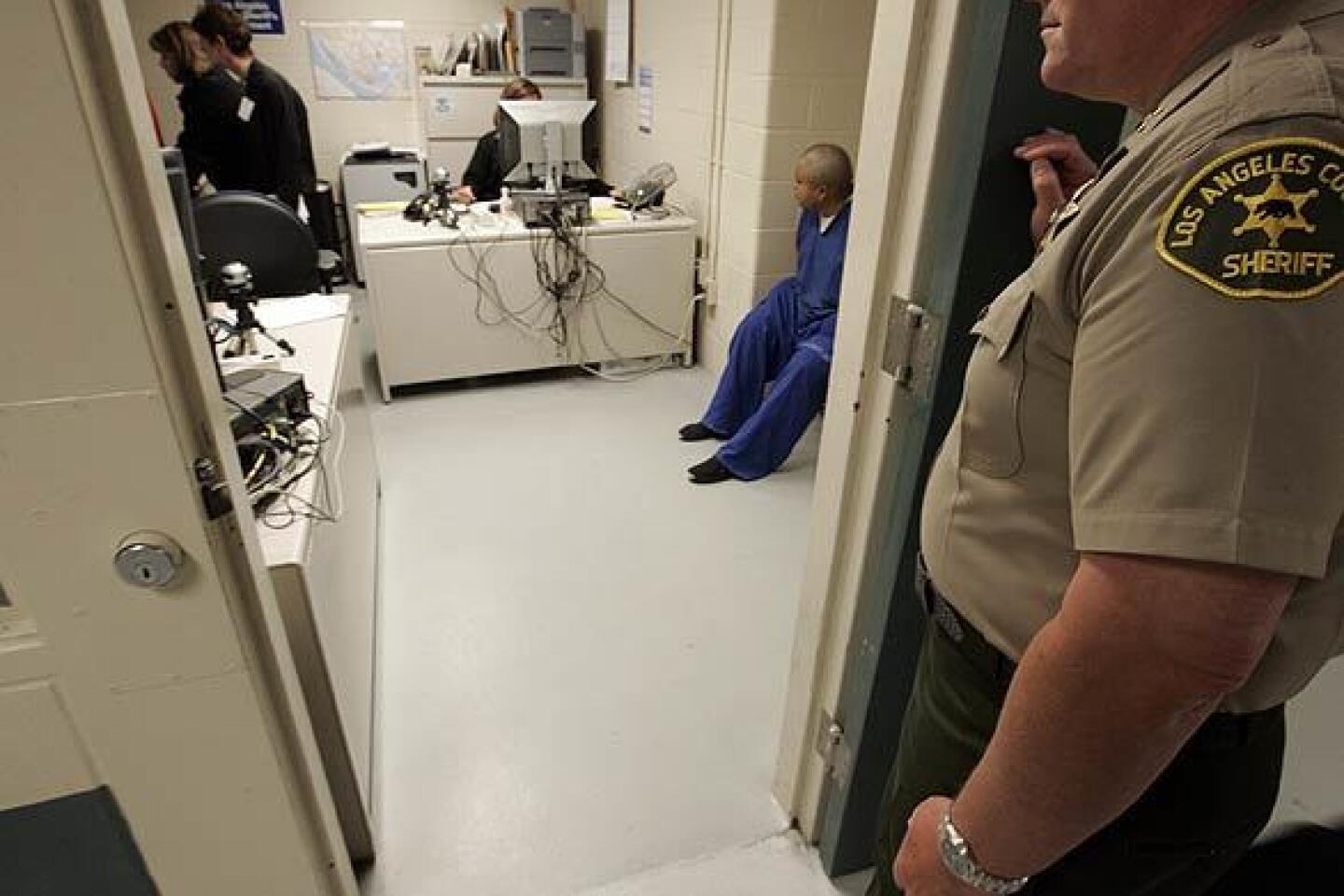

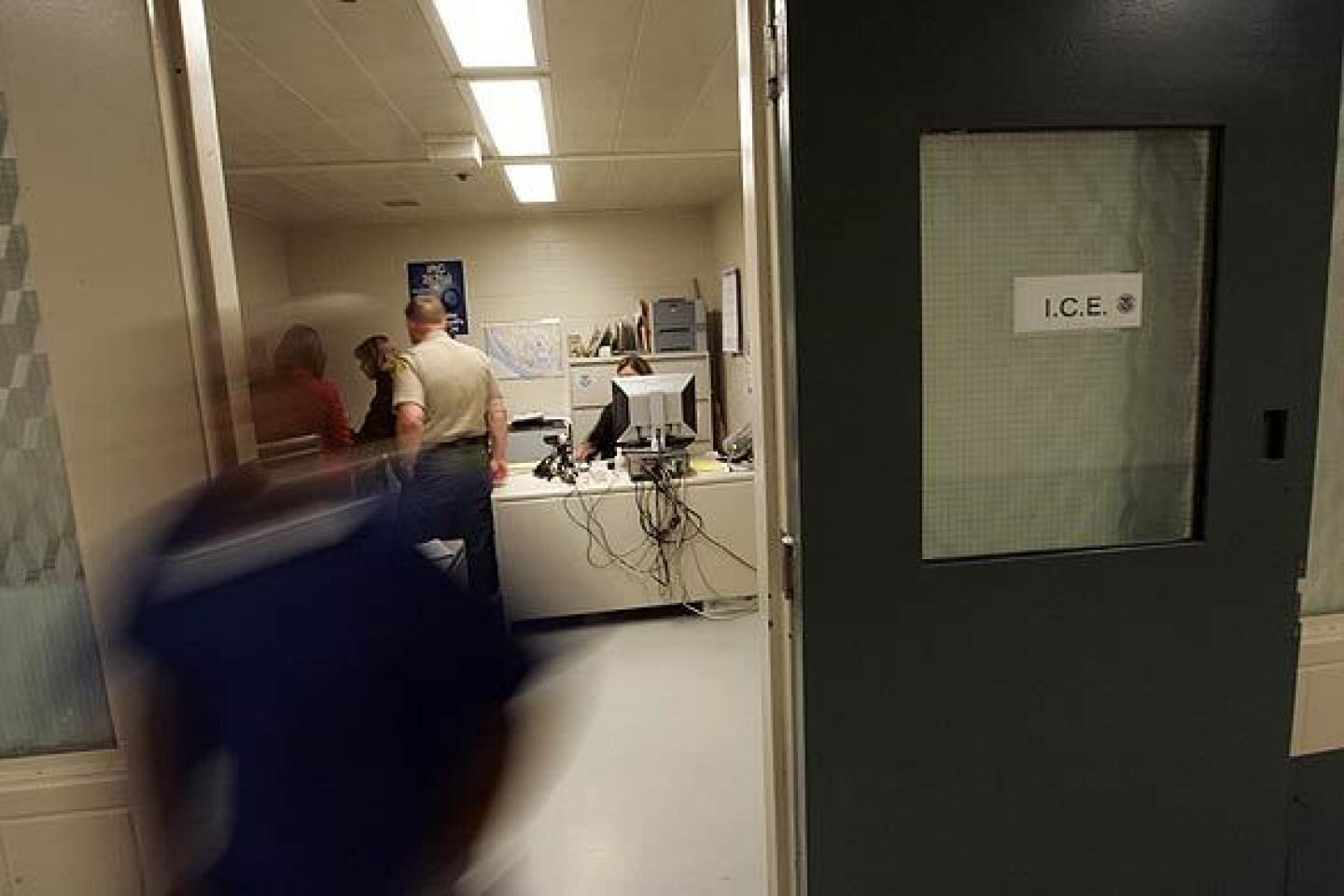

The inmates sit on a metal bench in a converted cell at a Los Angeles County jail. Many have served their time and are ready for release. But not before a quick interview.

Where were you born? Have you ever been deported? Did you know that a judge had ordered you to leave the country?

Sheriff’s officials, who have been trained by federal authorities to screen for illegal immigrants at the jail, have interviewed nearly 20,000 inmates since the controversial program began more than two years ago. They have referred 10,840 people to Immigration and Customs Enforcement for possible deportation.

Last week, the Sheriff’s Department received $500,000 in county funding to expand the jail screening and to increase the number of interviewers from eight to 13.

Sheriff’s officials said the screenings free up jail beds and ensure that illegal immigrants who commit crimes are deported, not released back into the community. Immigration authorities said the program allows them to focus limited resources on other enforcement efforts.

“We obviously have a tremendous amount of work to do in the United States to combat the issue of illegal immigration,” said Brian DeMore, Los Angeles field office director of the immigration agency. “We use these programs as a way to bolster our immigration authority.”

But there are still holes in the system. The process largely relies on inmates’ honesty about where they were born. The vast majority of interviews are conducted with inmates who have previously said they were born in another country. And even with more custody assistants, department officials say they won’t be able to interview 100% of foreign-born inmates.

“We do not talk to everybody,” said Sheriff’s Lt. Kevin Kuykendall. “We just don’t have the manpower.”

Pedro Espinoza, an illegal immigrant and alleged gang member, is accused of killing high school football star Jamiel Shaw II in March, one day after Espinoza was released from an L.A. County jail. Espinoza wasn’t red-flagged for an interview because he said during booking that he was born in the U.S., sheriff’s officials said. A judge ruled last week that Espinoza would be tried for murder.

Immigrant rights advocates criticize the screenings, saying that the sheriff’s custody assistants are not adequately trained in complex immigration law and that there is room for error that has led to the deportation of at least one U.S. citizen. They also say it discourages illegal immigrants from reporting crimes to the Sheriff’s Department.

“Local enforcement of immigration law is bad policy,” said Ahilan Arulanantham, staff attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California. “It sows distrust in communities. . . . The effect is going to be felt beyond the jail, even if the program is implemented only in the jail.”

Officials say that because the screeners are not sworn deputies, immigrants in the community shouldn’t feel intimidated by them.

The Sheriff’s Department began interviewing inmates at the beginning of 2006, making Los Angeles County the first in California to cooperate with federal authorities on immigration enforcement in the jails.

Last week, the county Board of Supervisors approved the expansion with a vote of 4 to 1.

Supervisor Mike Antonovich said that even though immigration enforcement is a federal job, the county suffers the consequences of illegal immigrants’ criminal activity and should do its part to help get them out of the U.S. “We are paying the cost when they come over and commit crimes,” said Antonovich, who voted for additional resources.

Roughly 4,000 inmates -- or one-fifth of the daily jail population -- are foreign-born, according to the Sheriff’s Department. About 3,100 inmates probably are eligible for deportation, the department said, either because they are illegal immigrants or because their criminal records have invalidated their green cards. Each week, custody assistants interview about 150 inmates who reported being born in another country. Federal immigration agents stationed at the jail interview about 100 additional inmates a week. Because there is no list of U.S. citizens, interviewers rely on state and federal computer databases that show criminal records and encounters with immigration enforcement. About 50 inmates a day are bused to immigration detention centers for further investigation.

According to a snapshot from 2007, about 87% of the inmates transferred to immigration custody were deported and about 9% went before immigration judges.

“If we weren’t doing this, all these criminal aliens would be released back into the community,” said Sgt. Deberah Lightel.

One recent morning, an inmate was scheduled to be released with an ankle bracelet for a driving under the influence conviction. Sheriff’s officials typed his name into an immigration database and came up with photos, fingerprints and a record showing that someone by that name had been born in Mexico and deported. After taking the inmate’s fingerprints, however, the officials realized it wasn’t the same person. But the inmate admitted he was also an illegal immigrant from Mexico who had been deported and had sneaked back into the U.S. An immigration hold was placed on him.

Another inmate, a gang member in jail on a robbery charge, told the custody assistant he had a green card. Despite that, she told him, his earlier drug convictions made him eligible for deportation to El Salvador. When she asked for his address there, he responded that he had no idea. He had come to the U.S., he said, when he was 6.

Next, a man in jail for traffic violations was called in for an interview because he had told law enforcement he was born in Mexico. But that morning, he claimed to have been born in Torrance.

“You’re not lying to me?” the custody assistant asked before grilling him on the name of the hospital where he was born and the schools he attended as a child. She asked if he had proof of U.S. citizenship. The inmate told her he had a Social Security number, which she checked against a database and determined that his story checked out. For the custody assistant, that was enough.

“You’re going to be bonded out,” she said. “Next time don’t state you’re from a foreign country.”

Down the hall in another converted cell, federal immigration agent Jose Luquin interviewed a Mexican immigrant with convictions for battery, grand theft and domestic violence. The immigrant had been deported twice and had paid a smuggler to help him reenter the U.S., where he was arrested for violating probation.

“Do I have to go back?” he asked, crying. “I have four kids. My wife is sick. I’ve been here all my life. . . . I feel American in my heart.”

“You have a judge’s order telling you you can’t be in the United States,” Luquin said before telling the inmate he would again be deported.

Similar scenes take place at jails around the nation every day, including those in Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has 30 agreements with local law enforcement agencies around the U.S. to conduct screenings in jails. There are programs in about 10% of jails nationwide and the others have 24-hour access to immigration authorities.

Now, Immigration and Customs Enforcement chief Julie Myers said the agency is unveiling a new program to “create a virtual ICE presence” in all jails nationwide by linking local law enforcement departments with Department of Homeland Security and Federal Bureau of Investigation databases. The technology, she said, will enable some of the screening to be done electronically without requiring interviews by immigration or local law enforcement agents.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.