Liberal Kevin de León found an unlikely stronghold in Republican California

- Share via

Kevin de León spent his longshot campaign against Sen. Dianne Feinstein arguing that she was not sufficiently fighting against President Trump and his conservative agenda in Washington.

But when election night came, De León ended up garnering strong support from some of California’s reddest counties, including those who want to break off from the liberal bastion to become the state of Jefferson.

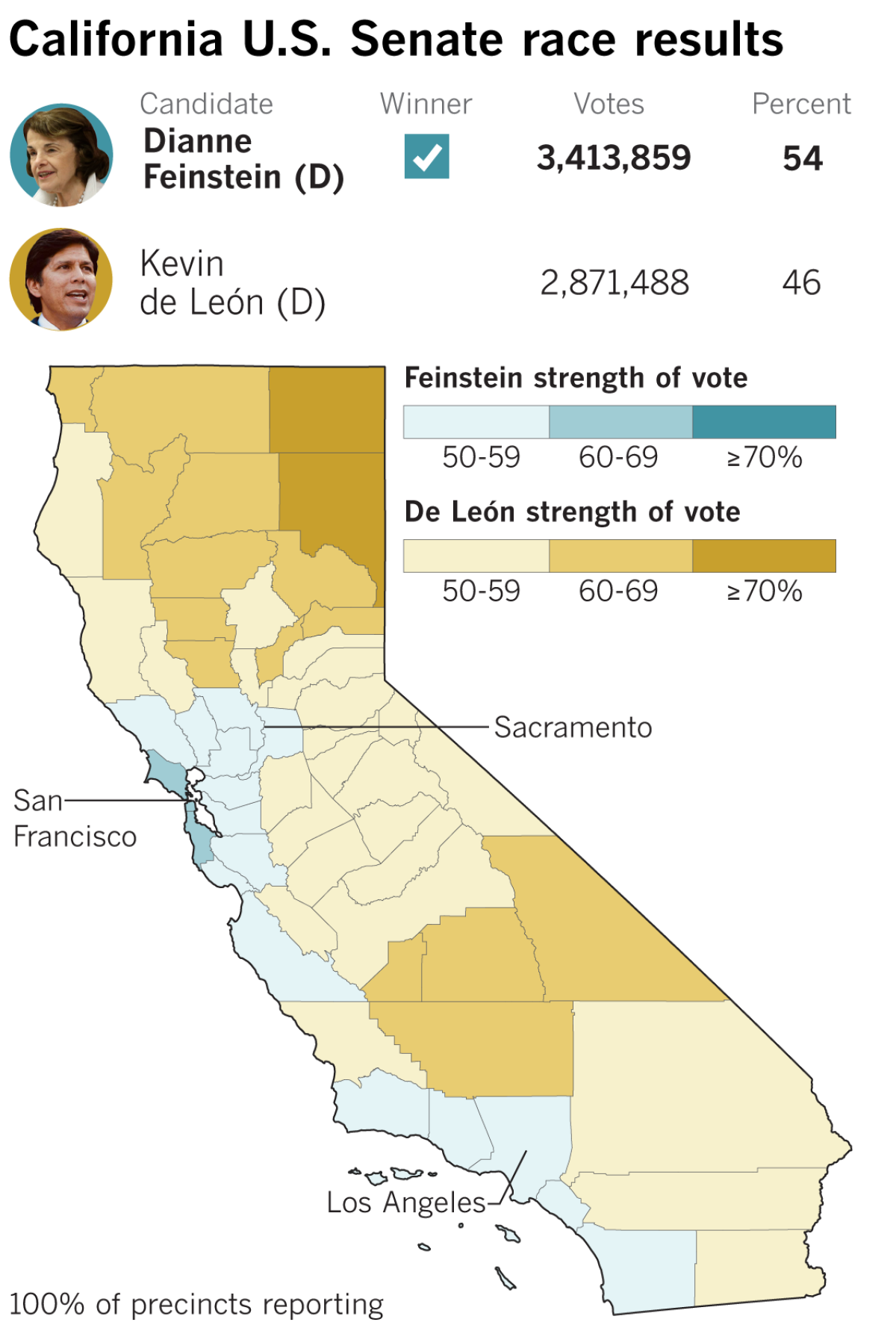

It was an ironic end to a race in which where De León always trailed in the polls and ended up losing 54% to 46%, according to preliminary figures.

Because two Democrats were the top primary vote getters, there was no Republican on the ballot. Before Tuesday, many policy experts thought droves of Republicans wouldn’t vote in the Senate race.

That seems to have happened to some degree — whereas 7.1 million people voted in the governor’s race, about 6.3 million voted for either Feinstein or De León.

Keith Smith, associate professor of political science at University of the Pacific, said he expected even more of a dropoff than that.

“Since she played such an outsized role in the Kavanaugh brouhaha, she became a focal point for Republican discontent in the process,” Smith said. “I do think there are a number of Republicans who otherwise might have sat out the election and chosen not to vote who did vote for De León because he wasn’t Feinstein.”

Feinstein, a ranking member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, became the target of more Republican ire than usual after the Kavanaugh hearings, with President Trump tweeting about the California Democrat and mentioning her while out stumping for Republican candidates.

In early October, Trump supporters chanted “Lock her up!” in reference to Feinstein as the president stood on stage and argued that Feinstein leaked the letter from Northern California psychology professor Christine Blasey Ford in which Ford accuses Justice Brett Kavanaugh of sexually assaulting her when they were teenagers. Trump didn’t start the chant, which was previously reserved for Hillary Clinton.

“You’re talking to a Kevin de León voter, and that’s plain and simple because I wanted to punish her for what she did to Brett Kavanaugh, and I did that even though I know a lot about De León,” said Bill Whalen, a research fellow at Stanford University ‘s Hoover Institution and former speech writer for Republican governor Pete Wilson.

Feinstein’s campaign disagreed that De León’s Republican support was from voters upset about Kavanaugh and argued that, instead, it was because people know where Feinstein stands on gun control, LGBTQ rights and abortion — and they know they disagree with her.

“They didn’t decide they were voting for Kevin because they agreed with him,” said Bill Carrick, Feinstein’s longtime strategist. “I think that, ironically, he was rewarded for being relatively unknown with Republican voters. That’s why I say he was the stealth Republican candidate.”

People on the other side of the aisle agreed with that assessment.

In the primary, De León did well among white progressives, Republican consultant Mike Madrid said, but in the general election, many of his votes likely came from white conservatives.

“What seemed his greatest weakness was actually De León’s greatest strength — his lack of resources didn’t allow him to interject himself into the campaign in a way that clarified what he stood for, and it became a straight referendum on Feinstein,” Madrid said.

In the end, De León won 40 of California 58 counties, many of them in rural areas that have long supported Republicans, according to early unofficial voter data. But he lost the most-populous counties, and not just deep-blue ones like Los Angeles and San Francisco. Feinstein carried Orange County as well as San Diego.

De León said people voted for him because he spent a substantial amount of time in the Central Valley and made campaign stops in the Inland Empire, talking to both Democrats and Republicans who expressed disdain over the “establishment authority.” He said he did not agree that he received votes because people didn’t know who he was.

“For the first time in 25 years, we had real conversation in California about the values we want represented in Washington,” De León said. “I’m proud to earn the support of nearly 3 million Californians and 70% of the counties across the state. Those numbers come as a shock to pundits and critics alike because I was never supposed to be here at all — a Latino kid with an Irish first name who grew up dirt poor, I have been constantly underestimated.”

De León was outspent — Feinstein entered the last few weeks of the race with more than a 10-1 cash advantage — meaning he never had enough in his campaign coffer to advertise on TV or on the radio, a key part of running in a state as large as California. He didn’t get a chance to tell voters his platform — and Feinstein didn’t make any effort to run attack ads telling residents why they shouldn’t vote for him.

The two met publicly only once for a “public conversation,” rather than a debate, in mid-October in San Francisco, and they stayed cordial toward one another.

Feinstein’s campaign strategy for the most part seemed to largely ignore De León and focus attention on her goals to pass healthcare reform and stronger gun control regulations.

That worked, as even though thousands of Republicans seem to have chosen her opponent, she had plenty of Democrats willing to give her what’s thought to be her final term in the Senate.

“This is a clear Kavanaugh effect,” said Thad Kousser, chair of the political science department at UC San Diego. “She faced a lot of criticism from national Republican leaders, including President Donald Trump, when Republicans were trying to make up their mind about who the lesser of two evils was in the Senate race. It doesn’t take much to swing someone when it’s a Republican choosing between two Democrats.”

Staff writer Sarah D. Wire contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.