PASSINGS: George Barrett, Enrique Zileri, Valeri Petrov, Steven R. Nagel

- Share via

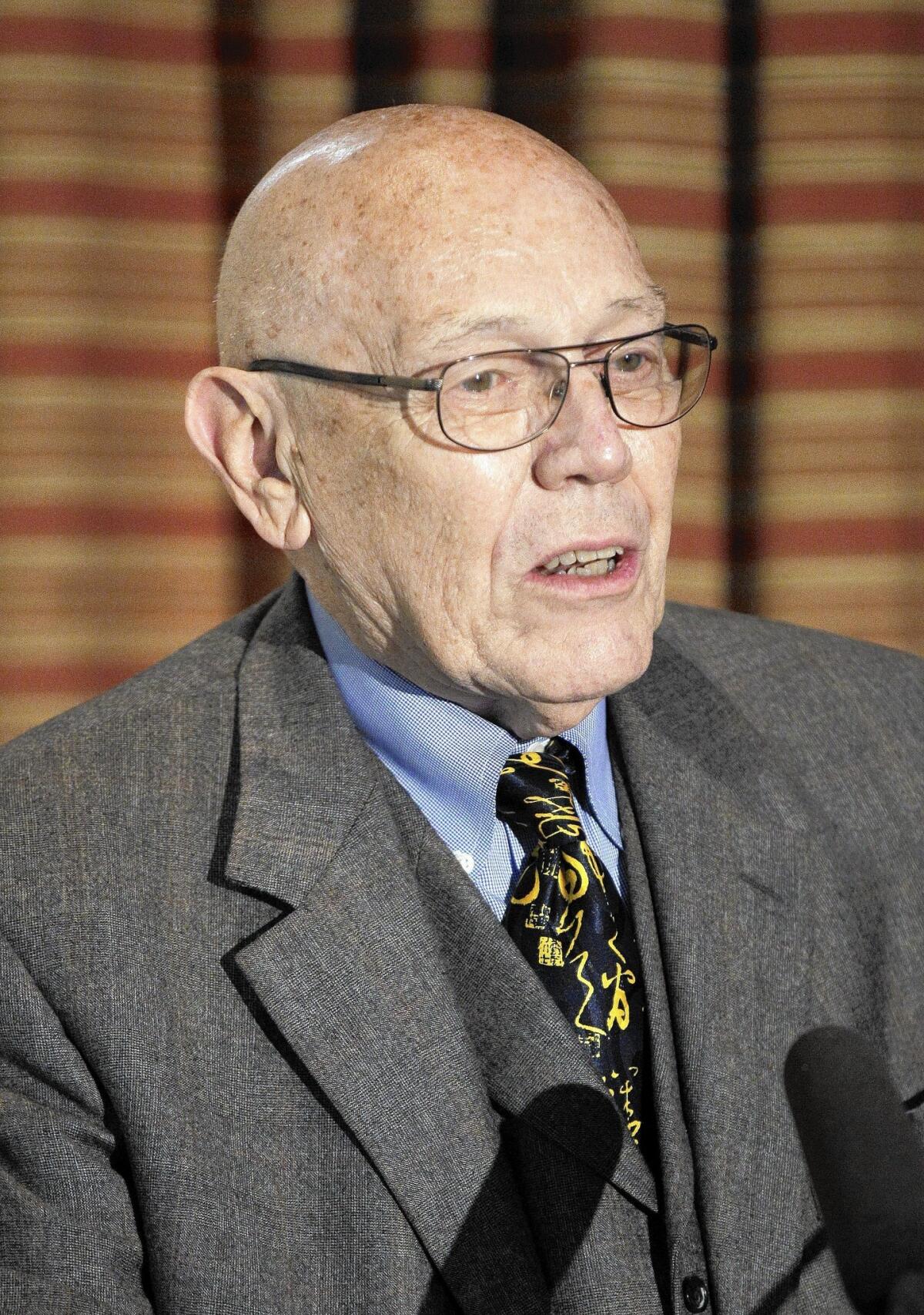

George Barrett

Tennessee lawyer fought for civil rights

George Barrett, 86, a Tennessee lawyer who represented civil rights plaintiffs for more than 50 years and helped end segregation of the state’s universities, died Tuesday at a hospital in Nashville, according to his law firm.

Barrett became a champion of the underdog, representing labor unions, antiwar demonstrators and teachers. In 1968, he took on the case of Rita Geier, a 23-year-old instructor at Tennessee State University who sued the institution over its plans to open a Nashville campus that she claimed would be mostly for white students. The state of Tennessee later agreed to provide funds for a diversified higher-education system after the lawsuit remained unresolved for more than three decades.

“I didn’t go to law school to be a corporate lawyer,” he often said. “I went to law school to represent working people.”

“Citizen Barrett,” as he was known, fought for the pensions and benefits of union members, sued on behalf of people denied the right to vote, and represented shareholders who had been defrauded by corporate management, according to Vanderbilt University, where Barrett studied law.

George Edward Barrett was born Oct. 19, 1927, in Nashville to a working-class Irish Catholic family. He completed a degree in social sciences at Spring Hill College in Mobile, Ala., in 1952 and received a diploma in economics and politics at Oxford University in England in 1953. He graduated with a law degree from Vanderbilt University in 1957.

“The temptation to disregard your compass, to withdraw, to be passive, to be silent is, and always has been, strong,” Barrett said in his keynote address to Spring Hill College’s Class of 2013. “The easy road is the status quo. Every day and time gives rise to the idea that it seems wise not to act, not to speak out against unjust power.”

Enrique Zileri

Head of Peru’s Caretas newsmagazine

Enrique Zileri, 83, who as longtime director of Peru’s leading newsmagazine defied despotism and battled corruption with stubborn independence, died Monday in Lima of complications from throat cancer, his family said.

Under Zileri, Caretas magazine was highly critical of the dictatorships that have afflicted modern Peru, Nobel literature laureate Mario Vargas Llosa said in a statement, calling him an “indefatigable defender of freedom and democracy” whose weekly publication “could never be bribed or intimidated.”

Zileri’s son, Marco, took over as Caretas’ editor in 2007. His daughter, Drusila, works principally for the weekly magazine’s society-focused sister publication, “Ellos y Ellas.”

Younger Peruvians remember Zileri for fashioning Caretas as a standard-bearer of press freedom in the 1990s as then-President Alberto Fujimori, now imprisoned, put fierce pressure on media independence.

Zileri’s most epic battles were against military dictator Gen. Juan Velasco, whose government deported him twice — in 1969 to Portugal and in 1975 to Argentina.

The government shut down Caretas six times from 1968-1977, once for nearly two years, said the magazine’s marketing director Katia Ysla Delgado. Enrique Zileri received a three-year prison sentence in absentia and was granted amnesty when Velasco fell, she added. In 1979, the ruling military junta closed the magazine again, this time for five months.

Caretas was founded by Zileri’s mother, Doris Gibson, in the 1950s. He later took over.

Zileri was a 1975 recipient of the Maria Moors Cabot Award from Columbia University for excellence in coverage of Latin America and the Caribbean.

Valeri Petrov

Bulgarian poet, translator and dissident

Valeri Petrov, 94, Bulgaria’s most prominent contemporary poet, who translated the complete works of Shakespeare, died Wednesday in a Sofia hospital after a stroke, his family said.

Besides poems, novels and translations from Russian, Italian and English, Petrov wrote numerous film scripts and playsfor adults and children.

Valeri Nissim Mevorah, better known by his pen name, Valeri Petrov, was born on April 22, 1920, in Sofia. During World War II, he took part in the resistance against the pro-Nazi regime in Bulgaria and remained close to left-wing political thought through his life.

In 1970, he clashed with the communist regime in Bulgaria after refusing to sign an official petition denouncing the awarding of the Nobel Prize to Soviet dissident Alexander Solzhenitsyn. As a result, Petrov was not allowed to publish for years, so he turned to translating.

Petrov was held in high esteem in his country and after the collapse of the totalitarian regime in 1989, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature by Bulgaria’s Writers’ Union, his family said.

Steven R. Nagel

NASA official, astronaut on four shuttle missions

Steven R. Nagel, 67, a former astronaut who flew on four space shuttle missions, died Aug. 21 after a long illness, NASA said in a news release. Longtime friend Ed Reinholtz said Nagel died of cancer in Columbia, Mo.

Nagel was a test pilot for the Air Force before becoming an astronaut in 1979. He was a mission specialist during a June 1985 Discovery flight and the pilot aboard the Challenger in October 1985, NASA said. He was commander on his last two missions — an Atlantis flight in April 1991 and a 10-day trip on Columbia in April 1993.

Born Oct. 27, 1946, in Canton, Ill., Nagel earned a bachelor’s degree in aerospace engineering from the University of Illinois in 1969 and a master’s degree in mechanical engineering in 1978 from Cal State Fresno.

After retiring from the U.S. Air Force in 1995, Nagel became a deputy director for Johnson Space Center’s safety, reliability and quality assurance office in Houston. The next year, he moved to the aircraft operations division, where he served as a research pilot, chief of aviation safety and deputy chief.

When Nagel retired from NASA in 2011, he joined the University of Missouri’s College of Engineering and taught in the department of mechanical and aerospace engineering.

--Times wire services

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.