Lawsuit against two former contractors may shed light on CIA’s use of torture

- Share via

Reporting from WASHINGTON — When Gul Rahman was taken to the “salt pit,” a then-secret CIA prison in Afghanistan, he was given a psychological evaluation by CIA contractor Bruce Jessen.

Jessen wanted “to determine which CIA enhanced interrogation techniques should be used on him,” a Senate intelligence panel report later concluded.

Over the next two weeks, the elderly Afghan farmer was forced to stay awake, subjected to total darkness and loud noises, was badly beaten and was dragged naked and hooded over dirt floors.

On Nov. 20, 2002, guards found him dead from hypothermia, dehydration, immobility and lack of food. The CIA would later determine that Rahman’s detention was a case of mistaken identity.

For the first time people who were involved in implementing and designing the CIA’s torture program will be compelled to answer for their conduct in federal court.

— Jameel Jaffer, attorney for the plaintiffs

Jessen and another former CIA contractor, James E. Mitchell, will face a federal court hearing Friday in Spokane, Wash., in a lawsuit that could shine a light onto one of the CIA’s darkest chapters, its use of torture. The Justice Department hasn’t tried to block the suit on security grounds, as it has in previous cases.

Between 2002 to 2008, harsh interrogation techniques developed and supervised by Jessen and Mitchell, both former Air Force psychologists, were used against 39 captives in CIA efforts to collect intelligence about Al Qaeda operations and future attacks.

In the suit, lawyers representing Rahman’s family and two other former CIA detainees allege that the psychologists promoted and taught torture tactics to the CIA based on 1960’s experiments involving dogs and an unproven theory called “learned helplessness.”

In 2014, the Senate Intelligence Committee released its so-called torture report, with gruesome details of how CIA officers abused detainees with waterboarding, beatings, slamming against walls and prolonged sleep deprivation.

The panel concluded that the CIA program violated the law and failed to disrupt any terrorist plots. The CIA disputed those findings, and said the investigation was flawed.

It also apparently opened the door for a lawsuit against the designers of the program.

On Friday, U.S. District Court Senior Judge Justin L. Quackenbush will consider Mitchell and Jessen’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit on grounds that they were working under direction of the government and their liability for any harm done in the interrogations is a “political question” for the White House and Congress to decide.

Quackenbush also will consider how much information the parties will be able to request from the government.

If he allows the case to proceed, “for the first time people who were involved in implementing and designing the CIA’s torture program will be compelled to answer for their conduct in federal court,” said Jameel Jaffer, who is representing the plaintiffs. “That is literally unprecedented.”

President Obama banned torture, waterboarding and other “enhanced” interrogation techniques when he took office in 2009. In 2012, then-Atty. Gen. Eric H. Holder Jr. said that no CIA officers involved in the interrogations would be prosecuted.

The question of how far the CIA should go has come up in the presidential campaign. Republican front-runner Donald Trump has campaigned on bringing back waterboarding and other harsh interrogation tactics. In December, he said the U.S. should target the families of terrorism suspects.

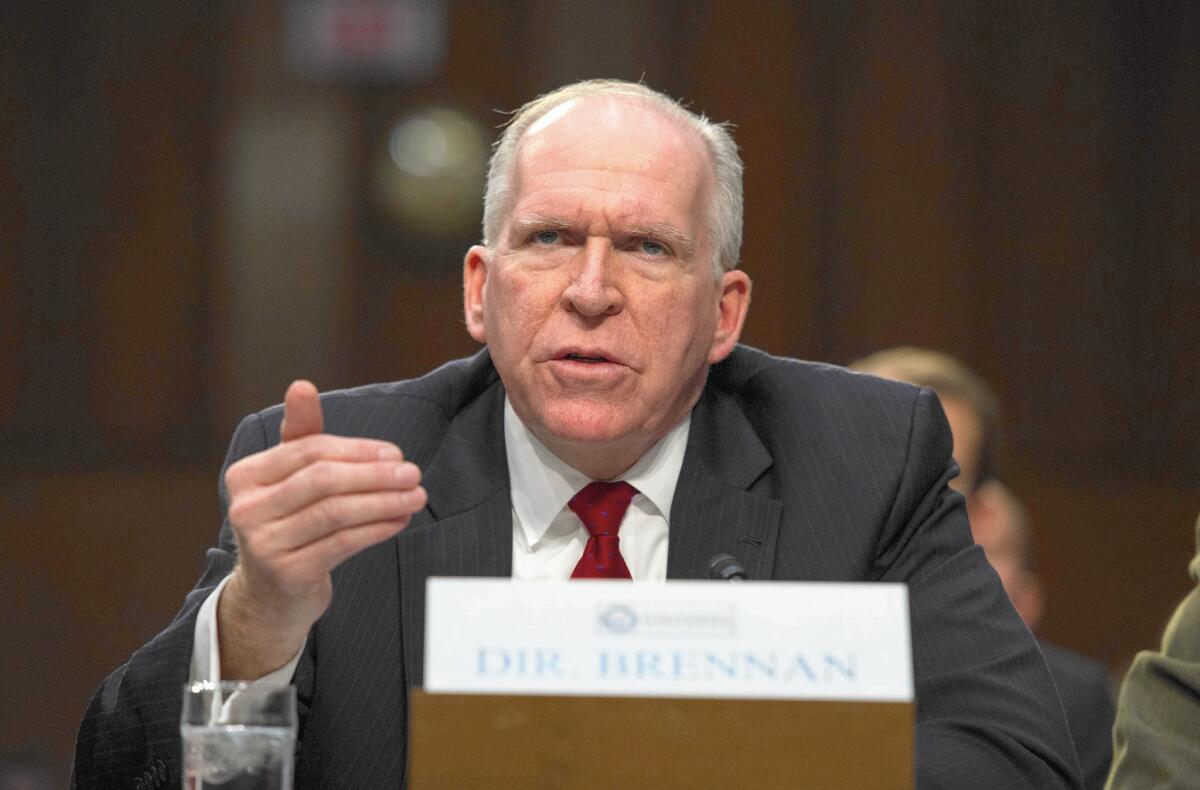

But CIA Director John Brennan, who was a senior CIA official when waterboarding was used, said this month that he would not carry out a similar order in the future.

“I will not agree to carry out some of these tactics and techniques I’ve heard bandied about, because this institution needs to endure,” Brennan told NBC News. “Absolutely, I would not agree to having any CIA officer carrying out waterboarding again.”

While in the Air Force, Mitchell and Jessen studied how torture had affected U.S. servicemen captured in the Korean and Vietnam wars. They then helped train U.S. airmen to resist and survive if captured by groups that do not adhere to the Geneva Convention ban on torture.

The CIA hired them in 2002 to design ways to persuade detainees to disclose information. The agency ultimately paid $81 million to the company they created to design and run interrogations at the CIA’s “black sites,” and then to evaluate the effectiveness of their methods.

The two men oversaw the interrogation of the self-proclaimed architect of the Sept. 11 attacks, Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, who was waterboarded 183 times, according to the Senate report.

Jessen and Mitchell’s actions amount to “war crimes” and “non-consensual human experimentation” in violation of U.S. law, the lawsuit states.

Lawyers for Rahman’s estate as well as two other detainees, Mohammed Ahmed Ben Soud and Suleiman Abdullah Salim, want Jessen and Mitchell to pay compensatory damages of more than $75,000, punitive damages and attorneys’ fees.

Ben Soud, a Libyan, was arrested in Peshawar, Pakistan, on April 3, 2003. He was held in secret CIA prisons for more than a year and subjected to aggressive interrogations, including being locked in a 3-foot-by-3-foot box, the lawsuit states.

He was sent back to Libya in 2004 and imprisoned there until 2011. He now lives in the Libyan city of Misurata and “continues to suffer deep psychological harm,” the suit says.

Salim, a Tanzanian, says he was abducted in March 2003 in Somalia and sent to the CIA’s “salt pit.” According to the lawsuit, he was sodomized, chained to the wall for days, fed bread soaked in water, and held in solitary confinement for 14 months. He was released in 2008 and now lives in Zanzibar, Tanzania.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.