Etan Patz case: Mistrial declared after jury deadlocks 11-1 in favor of guilt

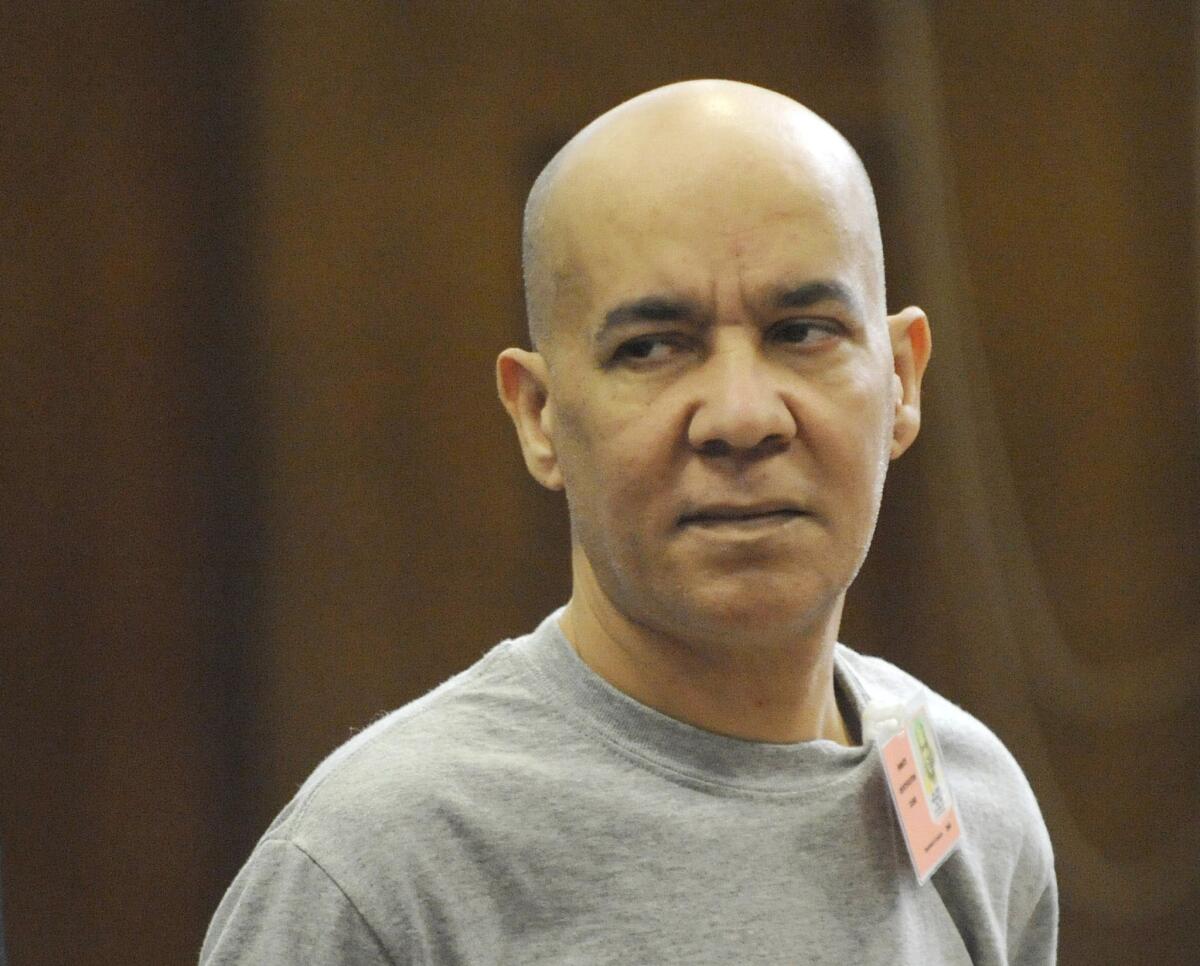

During his trial, Pedro Hernandez, in court in 2012, was shown on video confessing to killing 6-year-old Etan Patz. His lawyers said the confession was coerced.

- Share via

Reporting from New York — A judge declared a mistrial Friday in the case of a man charged with abducting and killing Etan Patz, a 6-year-old boy who vanished 36 years ago, after a lone holdout on the jury forced a deadlock in the more than three-month trial.

Jurors said they had voted 11-1 in favor of a guilty verdict.

The mistrial leaves one of the nation’s most baffling missing-child cases unresolved, but prosecutors said they would retry Pedro Hernandez, 54, who was a teenage store clerk when Etan vanished on May 25, 1979, while walking to a bus stop.

The seven-man, five-woman jury sent a note to Judge Maxwell Wiley on its 18th day of deliberations saying it was unable to reach a unanimous decision. It was the third time jurors had told Wiley they could not agree on Hernandez’s guilt or innocence.

The previous two times the jury said it was deadlocked, Wiley sent them back for more deliberations. This time, he accepted their decision.

At a news conference afterward, jurors said they were split from the beginning of their deliberations but that the gap lessened to 9-3 for guilt and then 10-2. It stuck at 11-1 in favor of conviction.

The holdout, Adam Sirois, said he was swayed by several factors, including a videotaped confession by Hernandez that he called “bizarre” and that the defense said was coerced.

“For me, his confession was very bizarre,” Sirois said at a news conference later. Sirois said two other elements of the defense case affected his decision: the claim that Hernandez was mentally ill, and the argument that another man, convicted pedophile Jose Ramos, was Etan’s likely killer.

“It does help to bring doubt into my mind,” Sirois said of the Ramos factor. “I could not get beyond reasonable doubt.”

Speaking to reporters after the jury was dismissed, Etan’s father, Stan Patz, said the family was “frustrated and very disappointed.”

“Our long ordeal is not over,” said Patz, who attended the trial each day, from its start in late January. He said he was convinced that Hernandez had kidnapped and killed his son, despite defense claims that police coerced Hernandez into making a false confession after his arrest in May 2012.

Manhattan Dist. Atty. Cyrus Vance Jr. said he, too, remained convinced of Hernandez’s guilt. “We believe there is clear and corroborated evidence of the defendant’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt,” Vance said. “The challenges in this case were exacerbated by the passage of time, but they should not, and did not, deter us.”

Hernandez’s defense attorney, Harvey Fishbein, said he was disappointed that there was no resolution but was ready to return to court to defend his client again when a date is set for his retrial.

“There’s only a resolution if the correct man is held responsible, and we firmly believe Pedro Hernandez is not the right man,” Fishbein said.

The deadlock followed several days of readbacks of key testimony from witnesses, and a complete readback of both sides’ closing arguments.

Prosecutors had built their case around a confession that Hernandez made to police after being arrested at his home in Maple Shade, N.J. The defense argued that Hernandez was coerced into confessing.

Etan’s disappearance spurred a national effort to improve efforts to trace missing children. Prosecution witnesses included Etan’s mother, Julie Patz, who testified about the morning she let Etan walk by himself to the school bus stop for the first time.

It was a “spur-of-the-moment” decision, she told the court.

Etan was never seen again, and his body has never been found. He was declared dead in 2001.

Tips led police to Hernandez, but Fishbein said the more likely culprit was Ramos, who was a friend of a young woman hired by the Patzes to walk Etan to and from school during the spring of 1979.

Fishbein also said that Hernandez had an IQ of about 70, could not always tell truth from fiction, and was tricked into confessing by police who pretended to be his friends.

Ramos, who is in prison in Pennsylvania on an unrelated case, has always denied involvement in Etan’s death, but Fishbein called witnesses who testified that Ramos had known Etan through his friend in 1979 and had spent time in the Patz apartment.

“The only evidence against Pedro Hernandez are his words. His words are unreliable,” Fishbein said of his client.

Prosecutors built their case around a video in which Hernandez tells police that he strangled Etan and then put his body into a box and left it in an alley in Manhattan’s Soho neighborhood. At the time, Hernandez was 18 and a clerk at a grocery store near the Patz apartment.

After Etan’s disappearance, his parents became active in efforts to improve the national tracing of missing children. Their son’s face was one of the first to appear on the side of milk cartons.

President Reagan opened the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children in 1984 and proclaimed May 25, the anniversary of Etan’s disappearance, Missing Children’s Day.

Bob Lowery, vice president of the center, said the Patz family’s efforts to rally law enforcement agencies to improve tracing efforts had changed the way the country responds to missing children.

“Etan started the missing child movement.” said Lowery. “There just wasn’t a lot being done in 1979.”

Etan’s case, in addition to two other high-profile missing child cases involving Johnny Gosch and Adam Walsh, sparked a snowballing effort that led to the center’s founding and that continues to evolve. Johnny Gosch was 12 when he vanished in Iowa in 1982; he never has been found. Adam Walsh was 6 when he was abducted from a Florida mall in 1981 and murdered.

Like Etan Patz’s parents, the families of the other boys helped push for better coordination among law enforcement agencies to expedite searches for missing youngsters. Nowadays, Lowery said it is far more likely that a missing child will be found because of advances such as Amber Alerts and the ability to quickly post and share online photographs of the missing.

“Technology has been a game-changer,” said Lowery. According to the center, the percentage of missing children it has helped find has grown from 62% in 1990 to 90% today. Amber Alerts alone have led to the recovery of 758 children since that program began in 1996, the center’s website says.

“In 1979, who knows – if Amber Alerts existed, or if there were surveillance cameras on street corners like there are today, could Etan have been found?” Lowery said. “That’s something we ponder every day.”

Some of the recoveries have been the result of abducted children spotting themselves on the website years later.

But technology has also brought new danger to children, because it allows predators to lure them via social media, Lowery said.

Etan’s body never was found, so the trial’s end does not necessarily mean the close of the case. However, Lowery said, the fact that it made it to trial shows that no matter how much time has passed, law enforcement agencies don’t give up trying to track missing children.

“If nothing else, it’s gratifying that missing children cases are not forgotten, even if it’s been 30 or 40 years,” he said. “Etan’s memory will never be lost.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.