As U.S. nuclear arsenal ages, other nations have modernized

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — As Russian forces were drawing back from a swift and violent incursion into Ukraine this fall, Moscow was delivering another powerful military statement many miles to the north.

A new 40-foot Bulava intercontinental ballistic missile, capable of delivering an unparalleled 10 nuclear warheads, was launched by a Russian navy submarine on a test run over the icy White Sea. The weapon was a clear signal to the world that as Russia battles tightening economic sanctions intended to block Moscow’s aggressive posturing on NATO’s frontiers, President Vladimir Putin has another card to play.

“I want to remind you that Russia is one of the most powerful nuclear nations,” Putin declared earlier this year at a state-sponsored youth camp. He reinforced the message last month, inviting the world to “remember what consequences discord between major nuclear powers could bring for strategic stability.”

The debate over how to modernize America’s aging nuclear forces has taken on increasing urgency with the emergence of a newly assertive Russia and a new generation of nuclear powers with increasing technological sophistication.

North Korea, Pakistan and India all are working quickly to improve their nuclear arsenals and delivery systems. By next year, China is expected to be capable of delivering a nuclear strike anywhere in the continental U.S. for the first time in its history — a threat that Russia has posed for decades.

While the nuclear confrontation between the United States and Russia cooled off after the 1991 fall of the Soviet Union, it has never ended. Indeed, the long-held hope for continual reductions in nuclear forces now seems unattainable, nuclear arms analysts say. For the first time in years, the U.S. and Russia each have increased the number of nuclear warheads deployed over the latest six-month monitoring period — the U.S. by 57 additional weapons and Russia by 131.

Russia is spending $560 billion on military modernization over the next six years with 25% allocated to aging nuclear forces, part of a program to replace all of its Soviet Union-era launchers. U.S. officials say it will take at least $355 billion over the coming decade to upgrade America’s nuclear arsenal and keep up with the rearmament spree underway in the rest of the world.

“Our rival powers are investing billions of dollars to modernize and improve their nuclear systems,” said Maj. Gen. Sandra Finan, Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center commander, warning that if the U.S. is “to remain credible,” it must maintain nuclear preparedness as a priority.

But veterans of the Cold War also say tit-for-tat responses in nuclear confrontation carry grave risks, anchored to erroneous assumptions that a nuclear exchange would leave one side in better condition than the other.

“God help us if we ever need them,” said Philip Coyle, a former nuclear weapons scientist, director of nuclear testing, senior Pentagon official and national security advisor.

The U.S. and Russia both continue to field land-based missiles that could be launched in a few minutes, submarine-based missiles able to deliver a devastating counterpunch to any surprise attack, and bombers that could loiter in threatening holding patterns above the Arctic.

A new strategic arms reduction treaty signed in 2010 limits deployed strategic warheads to 1,550 on each side, with a cap of 700 missiles and bombers by 2018. And over the last two decades, nuclear capabilities have been far from the U.S. military’s top priority. Most of the attention has gone to high-tech conventional weapons that evolved after the first Gulf War. Two decades have gone by without developing a nuclear strategic weapon.

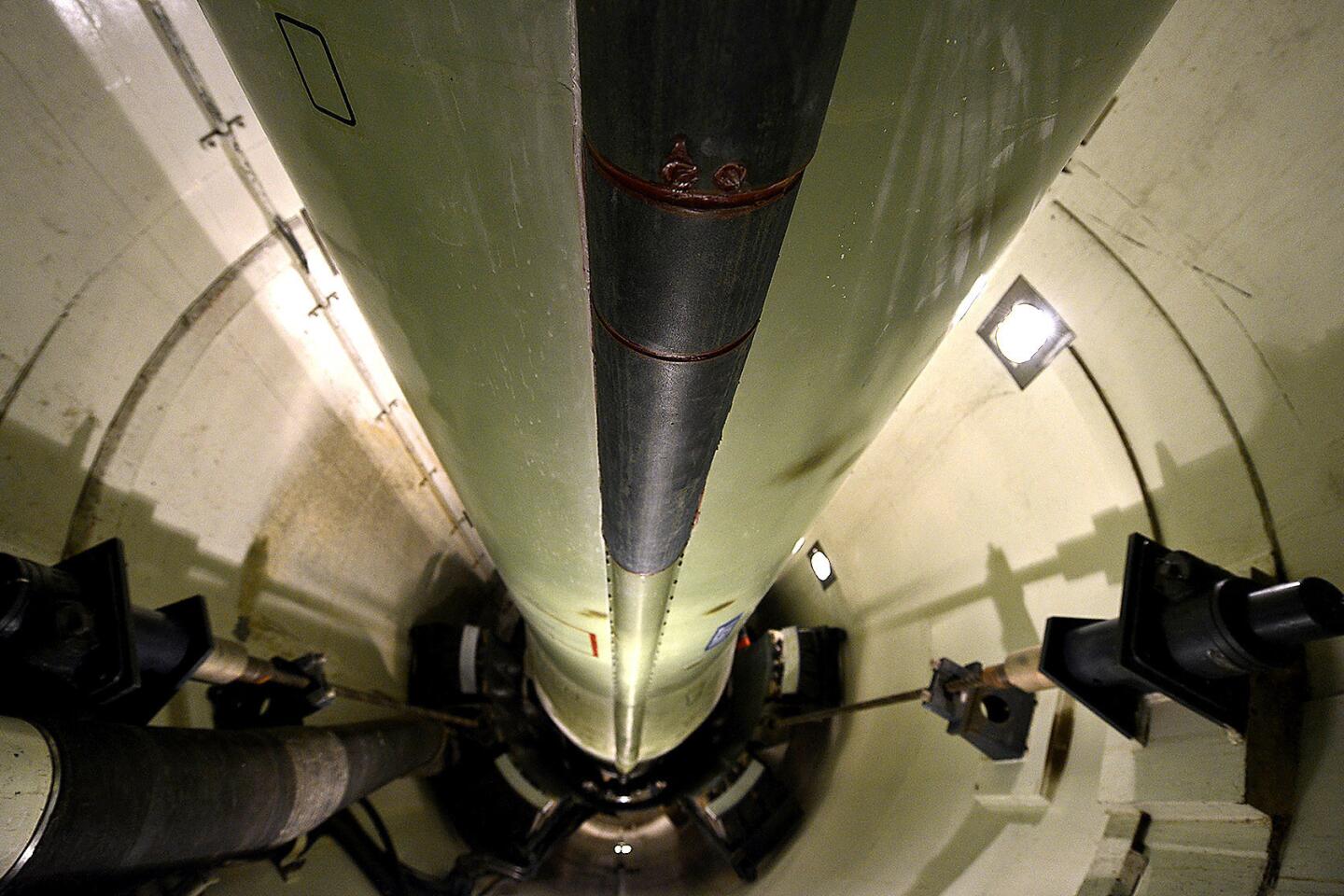

All the while, U.S. nuclear-capable bombers, submarines, intercontinental ballistic missiles and their launch-control bunkers have been allowed to become virtual Cold War museums.

***

In rural Great Falls, Mont., a small ranch house stands on the prairie with a sign at the gated entrance that reads “Ace in the Hole.” The house, tucked amid the rolling hills just off Highway 200, is a facade for what lies beneath it.

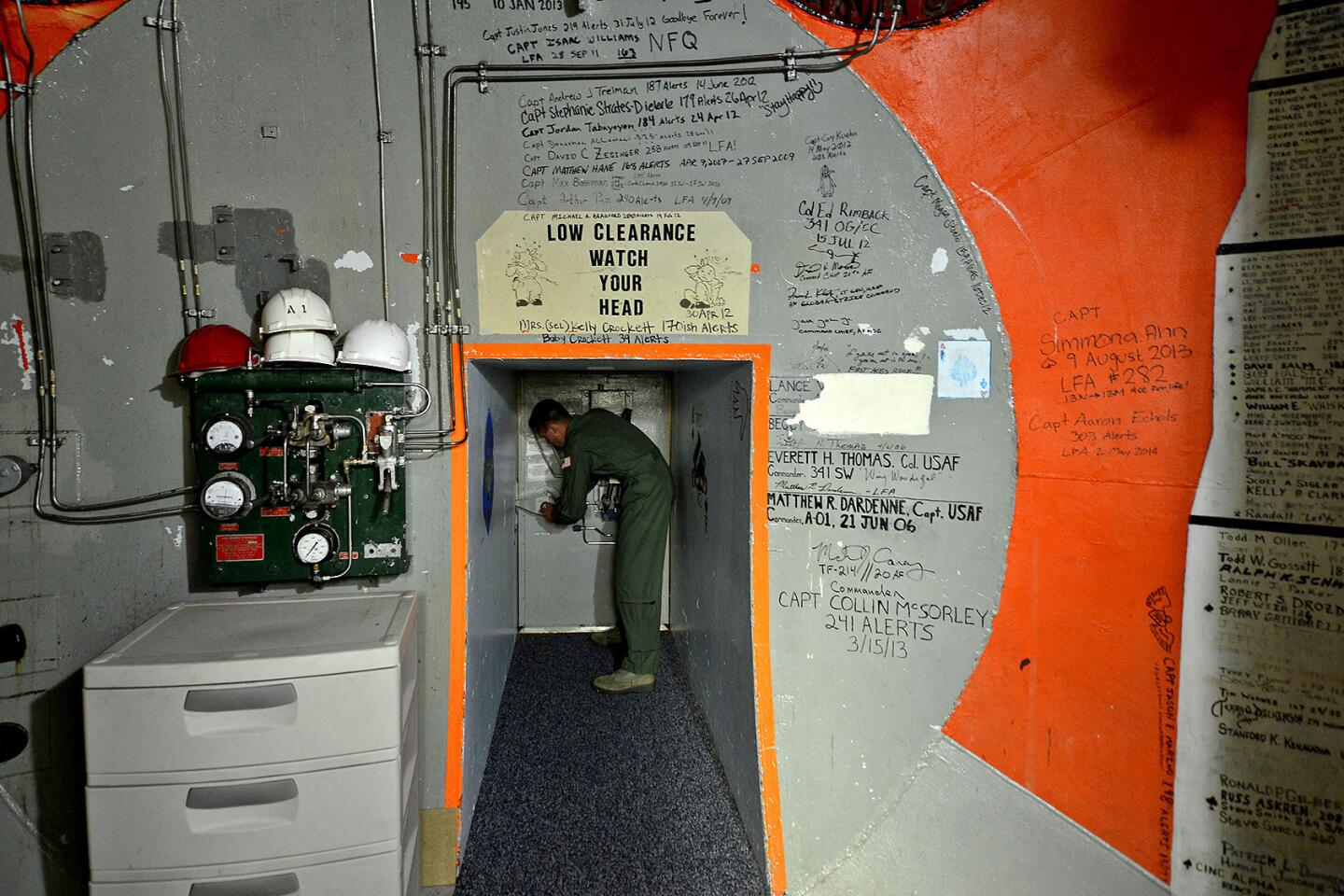

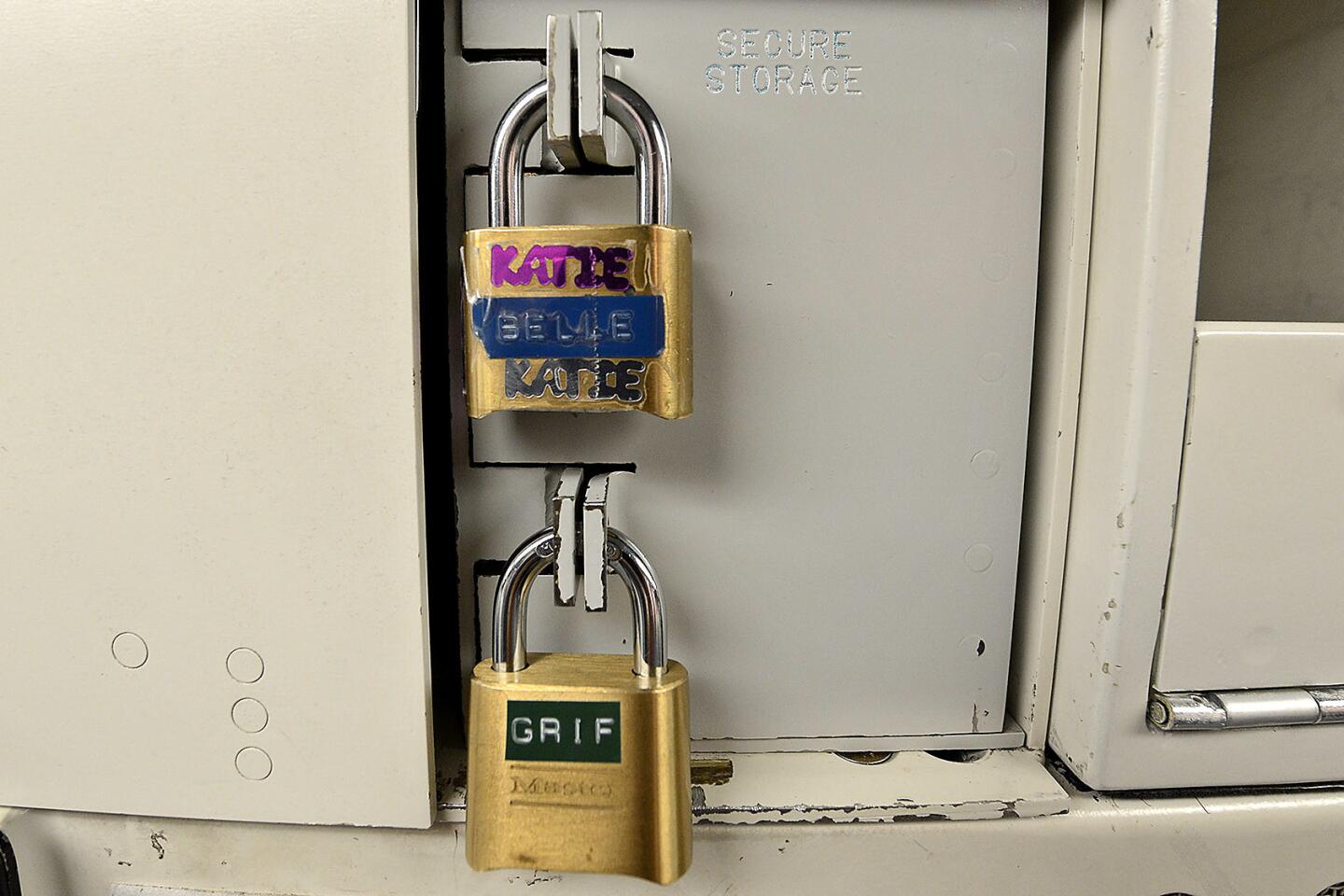

In a cramped capsule 70 feet below the house, Air Force Lt. Katie Grimley, 26, and Lt. Wesley Griffith, 28, command a fleet of 10 towering missiles capable of obliterating any spot on Earth in 30 minutes or less.

The underground capsule is one of many launch-control centers spread across 28,852 acres at Malmstrom Air Force Base. When it was first built, it was equipped with the latest gadgetry that 1962 had to offer.

Now, a 6-foot-high digital translator must be used to convert tones and whistles into signals a computer can read. The computers use 8-inch floppy disks that became obsolete even before the era of personal computers. Spare parts are so hard to find that on occasion they’ve had to be pulled from military museums.

“It’s a little like going back in time,” Griffith says.

It’s not just the missile launch centers: Each of the U.S. nuclear delivery systems is approaching obsolescence. The Air Force’s largest fleet of bombers dates back to the Kennedy administration. The Navy’s armada of missile-carrying submarines is nearing the end of its designed life, and the warheads they carry are nearly three decades old, on average.

Though the launch silo is a relic of the Cold War, it is routinely maintained and updated, and still provides the U.S. with a more lethal nuclear strike capability than that of any other nation. The debate over spending billions for modernization hinges in large part on how essential these Cold War systems remain when the most common security threats are low-tech insurgencies and domestic terrorist strikes.

***

The argument for upgrading got a boost this year in Ukraine, when Russia annexed the Crimean peninsula and supported separatists fighting to wrest control of the nation’s eastern provinces. In the midst of the crisis, Putin reminded the world that his nation remained “one of the leading nuclear powers” and that “it’s best not to mess with us.”

Russia’s newest missile, the RSM-56 Bulava, is submarine-based with a range of about 5,000 miles. After a series of failed test launches, the missile successfully conducted its first operational test last month from the new class of submarine, the Boreis.

In 2010, Russia deployed the land-based RS-24 Yars intercontinental ballistic missile on mobile launchers and in silos. It is designed to outsmart the U.S. missile defense system, according to a recent report by the National Air and Space Intelligence Center. Russia retains 1,200 warheads on its fleet of ICBMs.

The country has also been projecting power beyond its borders. Two months ago, in an exhibition that resembled a Cold War-era nuclear attack exercise, two Russian fighter jets, two long-range bombers and two aerial refueling tankers flew in international airspace near the coast of Alaska. They were intercepted by U.S. fighter planes and escorted out of the area.

NATO has conducted more than 100 intercepts of Russian aircraft this year, about three times more than in 2013.

China also is developing more potent missiles that will enable it to target any area of the U.S. for the first time.

Just last month, state-run media carried front-page stories on the launch of China’s first nuclear-powered submarine. The new fleet of subs, known as the Jin-class, will carry a dozen nuclear-tipped missiles capable of hitting the continental U.S. from the mid-Pacific, according to the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence.

Until now, China’s missiles could reach only the West Coast. The CSS-10 Mod 2, a solid rocket that can be launched from a mobile platform, is now being deployed with a nearly 7,000-mile range. And it is developing a variant with an 8,700-mile range. The intelligence center estimates that China will have about 100 ICBMs that could threaten the U.S. within a decade.

New threats are also looming from North Korea. The commander of U.S. forces in South Korea said he believed Pyongyang now had the ability to produce a miniaturized nuclear warhead and mount it on a missile. North Korea has had a string of failures in developing an ICBM, but continues its development of a missile with enough range to hit the U.S. It has shown at least one road-mobile ICBM in a military parade, though it has never tested it.

Iran, meanwhile, has a family of launch vehicles and is believed to be working on a missile with intercontinental range that could be deployed within years.

***

The $355-billion price tag for modernizing the aging U.S. “nuclear triad” of bombers, submarines and land-based missiles over the next decade may not even be realistic, according to Jeffrey Lewis, an analyst with the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies in Monterey. He said the actual expense, taking into account the tremendous spike in costs for new submarines, bombers and ballistic missiles, is likely to approach $1 trillion over the next 30 years.

The Air Force is able to maintain about 98% of its existing ICBMs on alert, despite their age, but even that comes at a high price. Upkeep expenses over the last three years have increased 36% to about $1.3 billion when compared to the same time frame a decade ago.

But can the U.S. afford to back away? Failure to maintain at least parity for U.S. nuclear forces could open the door to a fundamental recalculation in the balance of global power, analysts say.

Lewis notes that arms control treaties have been based on U.S. strength, not weakness. He worries that a failure to project a powerful level of nuclear readiness will leave the country vulnerable as foreign threats intensify — and actually undermine efforts to work eventually toward worldwide disarmament.

“I am an arms control guy,” he said, “who fears the budget problems are so deep that it will kill arms control.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.