VA finally making progress on benefits claims backlog

- Share via

Mike Dalton starts his day at a Department of Veterans Affairs office in Oakland doing something he couldn’t do a year ago: He signs on to a computer and calls up an application for disability compensation.

With a few mouse clicks, he pulls the information he needs to rate a veteran’s injuries.

The new computer system is the centerpiece of a major overhaul that department officials promise will clear the backlog of claims that has had severely wounded veterans waiting months — if not years — to find out whether they will receive financial help.

With pressure mounting from lawmakers, veterans groups and the media, the VA has been reorganizing its work flow, hiring more claims processors, revamping their training and requiring them to work 20 hours of overtime a month to clear the backlog.

There are signs of progress. On June 20, the department said it had processed 97% of the claims that had been pending for two years or longer, providing decisions in more than 65,000 cases.

As of Monday, more than 751,000 claims were pending nationwide, 457,000 of them for more than 125 days, the VA’s standard for timeliness. That is down 25% from a peak of 611,000 stalled claims in March, according to VA statistics. The figures do not include 250,000 claims under appeal.

“The backlog is now declining,” VA Secretary Eric K. Shinseki said at the national convention of the Veterans of Foreign Wars in July. “We are somewhat behind where we predicted and would have wanted to be, but that percentage will shift downwards quickly.”

Still, many veterans and their advocates are skeptical that the VA will meet its target of completing all claims within 125 days by 2015.

“The numbers have come down significantly, but to address the backlog by 2015 is still going to be a herculean task,” said Rep. Jackie Speier (D-Hillsborough), who co-hosted a town hall meeting with VA officials in San Francisco this year. Veterans at the meeting vented for hours about claims stalled because of lost paperwork, faulty decision making and bureaucratic red tape.

It took the VA nearly three years to develop and test the new computer system, which won’t have full functionality until next year. About half the cases are still being processed on paper.

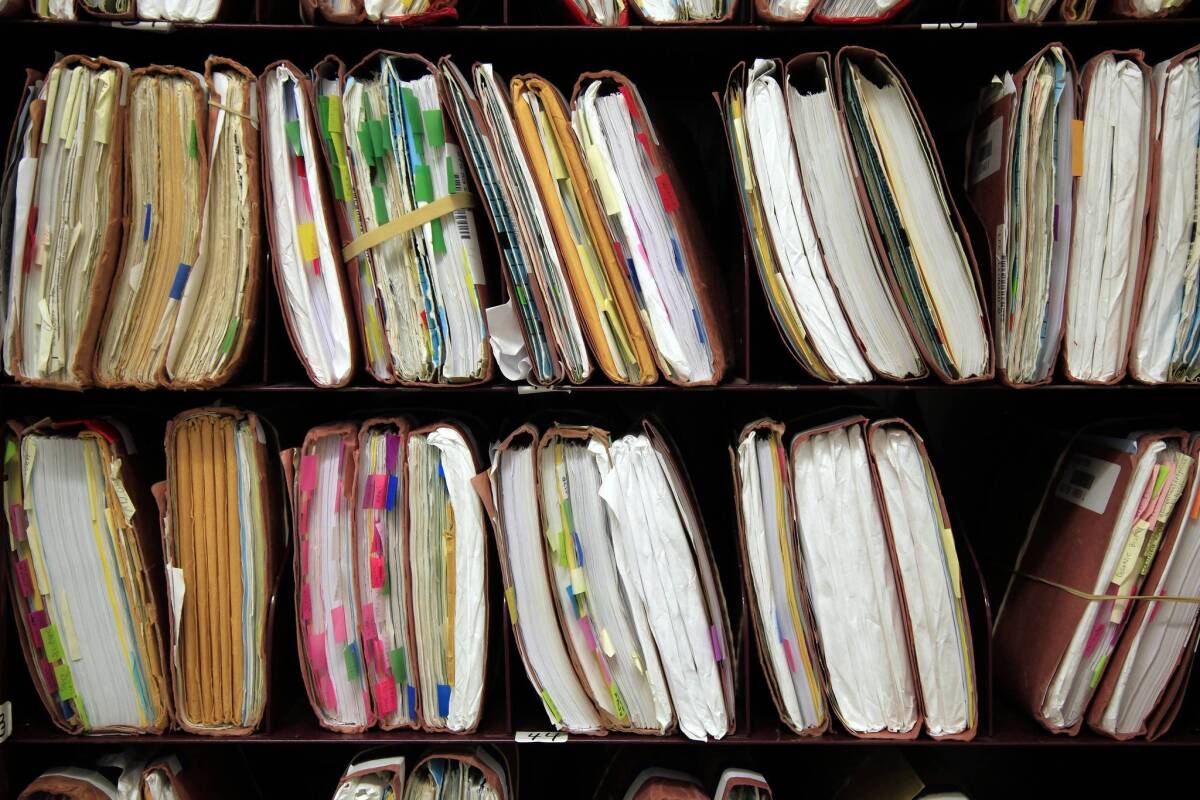

For Ann Rege, at the VA benefits office in Los Angeles, that means sorting through hundreds of pages of records to decide whether to increase a veteran’s compensation for a foot injury. The case lands on her desk in a bulging brown folder held together with rubber bands.

“Most of our members are under 30 years old. They don’t understand how this is a problem in the year 2013,” said Paul Rieckhoff, founder of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, which lobbies on behalf of the country’s newest veterans.

Wait times remain agonizingly long, averaging nearly a year at last count.

Veterans whose claims are processed in Los Angeles wait 588 days for a decision, longer than anywhere else in the country. In Oakland, the wait is 579 days; in San Diego, 350.

VA officials say the average wait times surged this year because of a decision to prioritize claims that had been pending the longest; the figures will drop when the older cases are cleared out. They promise to wrap up cases by the end of October that have been pending a year.

Rieckhoff’s group questions whether this level of effort can be sustained, and whether the accuracy of decisions might suffer. Even if the VA manages to eliminate the backlog by 2015, Rieckhoff said, “the real question is … what do these vets do in the meantime?”

In the time it took the VA to process Adam Legg’s claim, the Mammoth Lakes native had two vehicles repossessed and fell so far behind on his mortgage that he lost his home. The 284-day wait also took an emotional toll. “It was ingrained in me that it’s my job to take care of my family,” he said, “and I felt like a complete failure.”

A veteran of Iraq and Afghanistan, Legg, 31, struggled to find a civilian job when he left the Navy after the birth of a daughter in 2009. He tried working as a cook at a Florida bar and grill, but was hospitalized three times because of the strain to his back and knees, which he injured in service.

Although he now receives a $1,100 monthly disability check, the VA experience still leaves a bad taste.

“When you feel like the VA doesn’t care, you feel like the country doesn’t care,” he said. “Somebody willing to give their life for the country, they deserve a little better.”

Disability filings shot up in 2010, after the VA took steps to expand eligibility for compensation for conditions associated with exposure to the herbicide Agent Orange in Vietnam, Gulf War illness and post-traumatic stress disorder.

At the same time, a new generation of veterans was returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. The bad economy too played a role, officials say, making veterans more likely to seek compensation for ailments they might have shrugged off in the past.

Recent reports by the VA Office of Inspector General portray a system buried in paperwork. At one office in Winston-Salem, N.C., inspectors reported last summer, the floors were buckling under the weight of files that “appeared to have the potential to compromise the integrity of the building.”

The Oakland office doesn’t have room for all of its files. It can take days to pull them from one of several off-site storage facilities. Sometimes, paperwork is lost in the process.

VA officials are counting on the computer system to help turn things around. There are numerous time-saving features. Dalton, an Army veteran, showed off a tool that helps him calculate disability ratings using information provided by doctors on new, standardized questionnaires. Doctors’ notes can be hard to decipher, he said.

But the new system has limitations. Although it has built-in access to many records, others must be requested from the Defense Department and other federal agencies. Officials said obtaining a veteran’s in-service treatment records can take six months — maybe a year.

The departments of defense and veterans affairs have spent hundreds of millions of dollars in hopes of developing a single, shared electronic health record. To the frustration of lawmakers, they abandoned the idea in February.

The departments are now working on software that will allow them to access each other’s electronic health records. The Pentagon is also promising to begin transferring veterans’ complete service treatment records electronically by the end of the year.

Although veterans can file claims online, most still fax or mail them. Logging, sorting and entering the paperwork into the computer system can take weeks.

The Oakland and Los Angeles offices together ship about 85 boxes of files a week to a vendor in Wisconsin, which does the scanning. But, said Willie Clark, the western area director for the Veterans Benefits Administration, “the lion’s share of our work is still on paper.”

“That’s why you see claims folders everywhere,” he said. “That’s why you see mail — and all of us can’t wait until you won’t see this anymore.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.