Journalists launch legal assault on Missouri execution secrecy laws

- Share via

A coalition of mainstream news media intervened in the death penalty debate Thursday, filing a lawsuit in Missouri to contend that the public has a constitutional right to know where executioners get lethal injection drugs.

If successful, the lawsuit could have national implications. The journalists argue that the increasing secrecy around lethal injection executions violates the 1st Amendment.

“The public cannot meaningfully debate the propriety of lethal injection executions if it is denied access to this essential information about how individuals are being put to death by the state,” said the lawsuit, filed in state court by the Associated Press, the Guardian and Missouri’s three largest newspapers.

Specifically, the suit argues, the public has a “right to know the composition, concentration, quality and source of the drugs used in lethal injection executions.”

Execution secrecy laws in several states have come under fire from defense attorneys in recent years. Public officials are trying to keep the drugs’ sources secret as suppliers have become harder and harder to find.

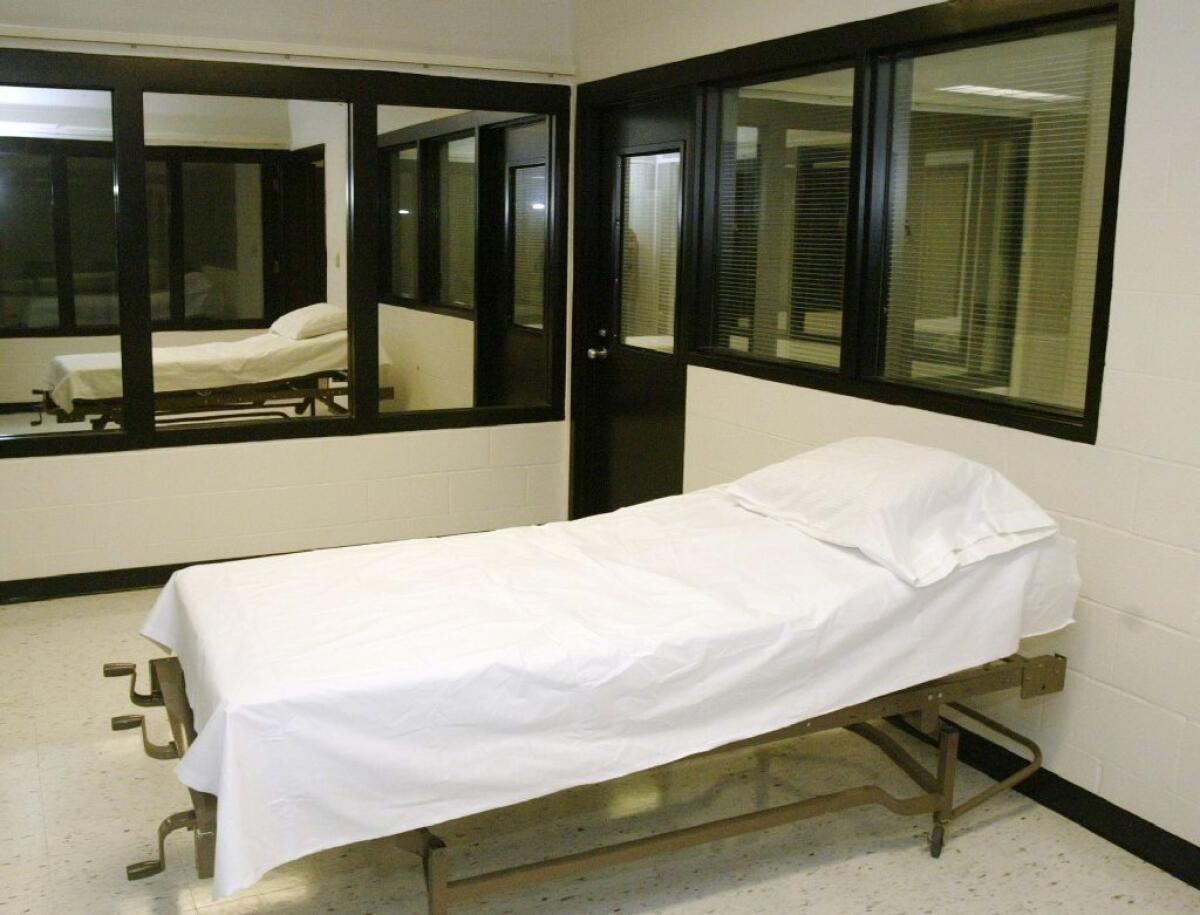

The policies have come under intense scrutiny since late April, when Oklahoma murderer Clayton Lockett writhed and gasped on an execution table until he had a heart attack 43 minutes after the lethal injection procedure had begun.

Oklahoma officials had used a secret, untested combination of lethal injection drugs to kill him and fought to deny Lockett’s attorneys detailed information about the chemicals it planned to use.

Thursday’s lawsuit in Missouri had been in the works for months -- and was filed the same day as a similar lawsuit by a St. Louis Public Radio reporter, the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press and the American Civil Liberties Union of Missouri.

Reporters involved in the lawsuits who spoke with the Los Angeles Times said they hadn’t known about each other’s lawsuits.

“Over a span of late October till now, [the Missouri Department of Corrections has] gradually been getting worse and worse about responding to open-records requests,” said Chris McDaniel, a St. Louis Public Radio reporter who has been covering capital punishment in Missouri.

In December, after Missouri prison officials began to dole out redacted records, McDaniel published an investigation revealing that the state’s execution drug supplier was an Oklahoma compounding pharmacy that wasn’t licensed in Missouri.

After that report, and a lawsuit filed by a death row inmate, the pharmacy agreed not to sell drugs to Missouri for an execution, cutting off the state from yet another supplier.

“Every time they reveal information, it’s not a good thing for them,” Deborah W. Denno, a professor at Fordham Law School and a death penalty expert, said of execution officials. “It reveals incompetence; they’re not knowledgeable about the procedure.... Departments of corrections have demonstrated to us over and over again that they need witnessing.”

Missouri’s laws keep secret the identities of execution personnel. It was in Missouri where one of those anonymous officials -- the man mixing the lethal drugs -- turned out to be a dyslexic physician who had trouble combining drugs and who have been the target of more than 20 malpractice suits and had been banned from two hospitals in his normal practice.

Alan R. Doerhoff was banned from participating in executions in Missouri in 2006.

In October, after receiving a public-records request from the ACLU of Missouri about lethal injection drugs, state officials reinterpreted the state’s personnel secrecy laws to include the lightly regulated compounding pharmacies supplying them with the drugs.

That’s when the spigot of information began drying up.

“You owe us about six months of records here,” McDaniel, the public radio reporter, said of his lawsuit against the Missouri Department of Corrections. (A spokeswoman for the state attorney general’s office declined to comment on the lawsuits.)

The denial of records was also grounds for the much broader 1st Amendment lawsuit by the AP, the Guardian, the Kansas City Star, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and the Springfield News-Leader.

The Guardian’s U.S. division -- the New York-based sister of the British newspaper -- spearheaded the effort, eventually securing the help of the media freedom and information access clinic at Yale Law School. The AP and then the newspapers signed on later.

“The Guardian, coming off the [National Security Agency and Edward Snowden] stories -- we’ve had a very strong secrecy phobia,” said Ed Pilkington, chief reporter for Guardian U.S., who has been closely covering executions for three years.

In that time, Pilkington watched defense attorneys fail to save their clients by arguing that the 8th Amendment bars such secrecy because of the possibility of cruel and unusual punishment, which would violate the U.S. Constitution.

“I was hearing it from various people, mostly lawyers working for death row inmates: Why doesn’t the Guardian launch a 1st Amendment challenge?” Pilkington said.

It’s not unprecedented for news outlets to join forces in court to try to pry open government proceedings. But Thursday’s lawsuit, which was designed by the Yale media freedom clinic, seeks to expand upon the media’s legal access to court hearings and records, said David Schulz, co-director of the clinic.

“The Supreme Court [has] held that the express rights of the 1st Amendment -- freedom of speech, freedom of press -- carried with them the implied right to know certain government information” to know how their government is run, Schulz said. “It’s sort of a structural guarantee that citizens have the information they need.”

Schulz added of the Missouri lawsuit: “This is kind of a direct extension of that theory into an application that is new.... If we get the precedent that this constitutional right exists, it would be applicable in other states.”

Missouri has executed three inmates this year. Its next execution is scheduled for May 21.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.