As Trial Nears, Case Against Airman Is Marked by Missteps

- Share via

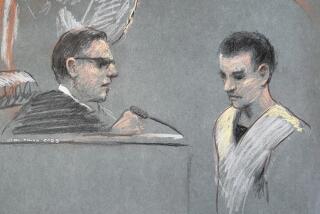

SACRAMENTO — When military investigators arrested him last year after the short flight from Guantanamo Bay, the prospects looked dreary for Senior Airman Ahmad Al Halabi. He had a cache of classified documents and a ticket to Syria in his pocket.

Allegations flew -- of espionage, aiding the enemy and attempting to pass off secret documents from the high-security military installation, home to hundreds of prisoners from the war on terrorism.

But his court-martial -- scheduled to open Tuesday at Travis Air Force Base in Northern California -- begins with the military’s case against him already damaged.

Nearly half of the 30 original charges against Al Halabi have been dropped amid revelations of sloppy evidence-gathering and defense claims of overzealous prosecution against the Muslim airman, a naturalized U.S. citizen born in Syria.

Last week, authorities revealed that a review by Defense Department security experts of more than 200 documents Al Halabi took out of Guantanamo found that one qualifies as a national secret.

Even before that announcement, Air Force Times editorialized that the military’s performance was “inexcusable and amateurish.”

Al Halabi, 25, was one of three Muslims arrested last year on suspicion of playing a role in a reputed spy ring at Guantanamo Bay’s high-security Camp Delta, which houses more than 600 prisoners believed to be aligned with Al Qaeda or the Taliban.

Military officials in March dropped prosecution of Army Capt. James Y. Yee, a Muslim military chaplain who served more than two months behind bars. Military officials expressed fears that a trial might reveal important national secrets, but critics speculated that the Army simply didn’t have a good case. A third suspect, civilian translator Ahmed Fathy Mehalba, has been jailed for nearly a year, and his case is unresolved.

As the Al Halabi trial opens, defense attorneys expect to press the military judge, Col. Barbara Brand, to dismiss the 16 remaining counts, which include attempted espionage and disobeying orders. If convicted, the youthful-looking airman could face up to life in prison.

“We’ve said from Day 1: He’s not a spy,” said Donald Rehkopf Jr., a civilian attorney from Rochester, N.Y., who is part of Al Halabi’s defense team. “All he is guilty of is being born in the wrong country and worshiping the wrong God.”

Military prosecutors are barred from commenting during the case, but an Air Force spokesman issued a release saying the government’s main goal “remains the same: to ensure Senior Airman Al Halabi receives a fair and impartial court-martial.”

Al Halabi was apprehended in July 2003 at the Naval Air Station in Jacksonville, Fla., as he returned to the U.S. after an eight-month stint as an Arabic translator at Guantanamo. He was carrying a plane ticket to Syria and $1,500 in cash. Agents also intercepted a box containing several classified documents, clothes and other personal items that Al Halabi had mailed to himself at Travis, his home base.

Investigators accused him of planning the Syria trip to pass off secret documents, including more than 180 letters from prisoners typed into his personal computer, a map of the highly restricted prison camp, the flight paths of military aircraft into and out of the island enclave and information detailing the names and cellblock numbers of prisoners. Calling him technologically savvy, investigators warned that Al Halabi might have already dispatched secrets via e-mail.

Al Halabi’s attorneys say he was indeed going to Syria, to get married. They plan during the trial to call witnesses and provide documents verifying the preparations for the ceremony.

Defense attorneys say the documents mailed back to the base or discovered in his luggage have proved to be innocuous or easily explained. For example, Al Halabi received permission from supervisors to type the translated letters from prisoners into his personal laptop because the military didn’t have enough government computers to go around, defense attorneys say.

Al Halabi spent more than nine months in jail after his arrest, but on May 12, he was ordered released and confined to base, where he has resumed his job as a supply clerk. A devout Muslim, he has asked to be allowed off base to attend weekly services, but his commander denied the request.

Born in Syria, Al Halabi moved at 15 to the U.S. to rejoin his father and older siblings, who had immigrated for economic opportunity. He went to high school in Dearborn, Mich., a heavily Muslim pocket of suburban Detroit. After working in the family restaurant, Al Halabi chose a career in the military as a way to more easily afford a college education.

The case has generated support among Muslims in California and Michigan. A group in Orange County, where Al Halabi’s older sister lives, formed a nonprofit organization to raise more than $50,000 toward his defense. “We’re praying all the charges against him will be dropped,” said Shereen Sabet, a spokeswoman for the Airman Halabi Justice Committee.

Heading into the trial, defense attorneys have argued that the case against Al Halabi springs in part from the role he and Yee played in airing concerns about human rights violations at the Guantanamo prison. Court records say that Al Halabi and Yee both drew attention on base because of complaints some had deemed anti-American.

Although military investigators raised serious allegations after Al Halabi’s arrest, the case has been plagued by human error in the months since.

Tech Sgt. Marc Palmosina handled the investigation early on. But in an embarrassing moment for the Air Force, he was replaced after being arrested for allegedly mishandling classified documents. He also faced charges of rape and sodomy of a child under 12.

Special Agent Lance Wega, a rookie investigator who took over the case, pressed suspicions that Al Halabi may have passed secrets over the Internet, even though a computer expert told the investigator there was no proof that classified material had been sent from the airman’s laptop.

An intercepted letter to Al Halabi from the Syrian embassy in Washington was initially mistranslated, prompting agents to theorize that the airman planned to go to Qatar to meet enemy agents. But defense attorneys say the letter only gave him permission to return to Syria for his wedding.

Investigators also have been accused of mishandling the documents and personal items Al Halabi mailed home from Guantanamo. After going through the box to find what he called “smoking gun” evidence, Wega and other investigators broke out beers to celebrate. But they soon realized they should have worn gloves during the search.

According to court testimony, they repacked the box, pulled on plastic gloves and then repeated the process, photographing it as they went.

During recent hearings, defense attorneys also complained that the assistant trial counsel, Air Force Capt. Dennis Kaw, pressured a prosecution translator to withhold evidence that might help Al Halabi.

Staff Sgt. Suzan Sultan testified during a hearing in June that she discovered an error in her translation of the Syrian embassy letter. When she approached Kaw to ask whether she could return to the witness stand to correct her error, the prosecutor urged her not to, she testified.

Brand, the military judge, ordered an ethics review of the alleged misconduct by Kaw. The prosecutor has since left the Air Force.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.