20 years later, Abu Ghraib detainees get their day in U.S. court

- Share via

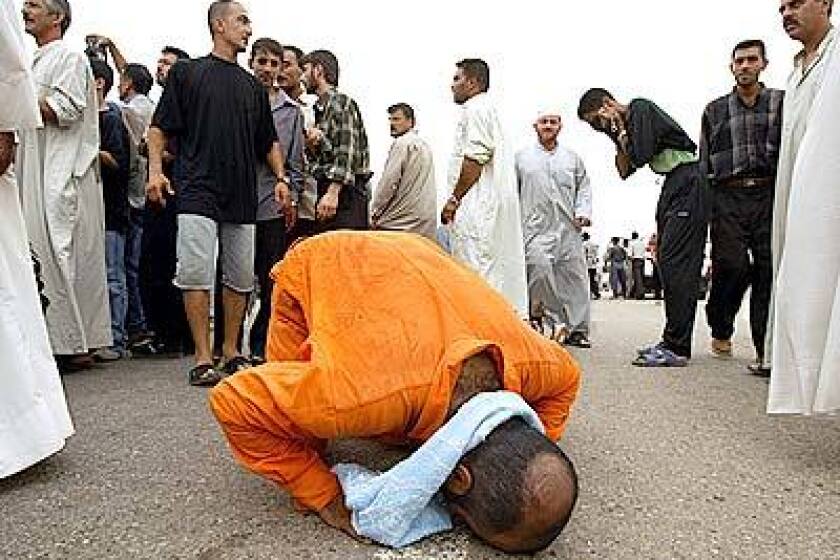

ALEXANDRIA, Va. — Twenty years ago this month, photos of abused prisoners and smiling U.S. soldiers guarding them at Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison were released, shocking the world.

Now, three survivors of Abu Ghraib will get their day in U.S. court against the military contractor they hold responsible for their mistreatment.

The trial is scheduled to begin Monday in U.S. District Court in Alexandria, Va., and will be the first time that Abu Ghraib survivors are able to bring their claims of torture to a U.S. jury, said Baher Azmy, a lawyer with the Center for Constitutional Rights representing the plaintiffs.

The defendant in the civil suit, the Virginia-based contractor CACI, supplied the interrogators who worked at the prison. The contractor denies any wrongdoing and has emphasized throughout 16 years of litigation that its employees are not alleged to have inflicted any abuse on any of the plaintiffs in the case.

Sgt. Provance, who yearns for combat rather than intelligence work, says he has suffered for blowing the whistle on abuse.

The plaintiffs, though, seek to hold CACI responsible for setting the conditions that resulted in the torture they endured, citing evidence in government investigations that CACI contractors instructed military police to “soften up” detainees for their interrogations.

Retired Army Gen. Antonio Taguba, who led an investigation into the Abu Ghraib scandal, is among those expected to testify. His inquiry concluded that at least one CACI interrogator should be held accountable for instructing military police to set conditions that amounted to physical abuse.

There is little dispute that the abuse was horrific. The photos released in 2004 showed naked prisoners stacked into pyramids or dragged by leashes. Some photos had a soldier smiling and giving a thumbs up while posing next to a corpse, or detainees being threatened with dogs, or hooded and attached to electrical wires.

The plaintiffs cannot be clearly identified in any of the infamous images, but their descriptions of mistreatment are unnerving.

Suhail al Shimari has described sexual assaults and beatings during his two months at the prison. He was also electrically shocked and dragged around the prison by a rope tied around his neck. Former Al Jazeera reporter Salah al Ejaili said he was subjected to stress positions that caused him to vomit black liquid. He was also deprived of sleep, forced to wear women’s underwear and threatened with dogs.

CACI has said the U.S. military is the institution that bears responsibility for setting the conditions at Abu Ghraib and that its employees weren’t in a position to be giving orders to soldiers. In court papers, lawyers for the contractor group have said the “entire case is nothing more than an attempt to impose liability on [CACI] because its personnel worked in a war zone prison with a climate of activity that reeks of something foul. The law, however, does not recognize guilt by association with Abu Ghraib.”

The case has bounced through the courts since 2008, and CACI has tried roughly 20 times to have it tossed out of court. The U.S. Supreme Court in 2021 ultimately turned back CACI’s appeal efforts and sent the case back to district court for trial.

In one of CACI’s appeal arguments, the company contended that the U.S. enjoys sovereign immunity against the torture claims, and that CACI enjoys derivative immunity as a contractor doing the government’s bidding.

But U.S. District Judge Leonie Brinkema, in a first-of-its-kind ruling, determined that the U.S. government can’t claim immunity when it comes to allegations that violate established international norms, like torturing prisoners, so CACI as a result can’t claim any derivative immunity.

The highest-ranking soldier charged with beating and humiliating Iraqi detainees at the Abu Ghraib prison and snapping keepsake photos of the deeds was sentenced in military court today to eight years in prison for abusing detainees.

Jurors next week are also expected to hear testimony from some of the soldiers who were convicted in military court of directly inflicting the abuse. Ivan Frederick, a former staff sergeant who was sentenced to more than eight years of confinement after a court-martial conviction on charges including assault, indecent acts and dereliction of duty, has provided deposition testimony that is expected to be played for the jury because he has refused to attend the trial voluntarily. The two sides have differed on whether his testimony establishes that soldiers were working under the direction of CACI interrogators.

The U.S. government may present a wild card in the trial, which is scheduled to last two weeks. Both the plaintiffs and CACI have complained that their cases have been hampered by government assertions that some evidence, if made public, would divulge state secrets that would harm national security.

Government lawyers will be at the trial ready to object if witnesses stray into territory they deem to be a state secret, they said at a pretrial hearing April 5.

Photos of Iraqi prisoners tethered to dog leashes and electrical wires dominated the news when they emerged in 2003 and 2004.

Brinkema, who has overseen complex national security cases many times, warned the government that if it asserts such a privilege at trial, “it better be a genuine state secret.”

Jason Lynch, a government lawyer, assured her, “We’re trying to stay out of the way as much as we possibly can.”

Of the three plaintiffs, only Al Ejaili, who now lives in Sweden, is expected to testify in person. The other two will testify remotely from Iraq. Brinkema has ruled that the reasons they were sent to Abu Ghraib are irrelevant and won’t be given to jurors. All three were released after periods of detention ranging from two months to a year without ever being charged with a crime, according to court papers.

“Even if they were terrorists it doesn’t excuse the conduct that’s alleged here,” she said at the April 5 hearing.

Barakat writes for the Associated Press.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.