After 25 Years, Woman Sees Son in His Fight for Freedom

- Share via

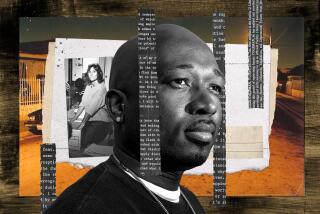

Thomas Goldstein came into the Long Beach courtroom in shackles. Geri Goldstein sat in the front row, a cane leaning beside her. Only about 10 feet separated a mother and son who had not laid eyes on each other in more than 25 years.

They didn’t get much further than hello.

“Hey,” the prisoner said to his 76-year-old mother. Geri Goldstein said hello back. A bailiff intervened. In a preliminary hearing on murder charges, he said, conversation between a defendant and spectator is prohibited.

“I’ll see you tomorrow,” Goldstein told her son.

She will see him behind bars, where Thomas Goldstein has been since he was convicted in 1980 of the murder of John McGinest on a Long Beach street. He has remained in custody despite court rulings that overturned his conviction on the grounds that prosecutors denied him a fair trial.

As prosecutors and defense lawyers wrangled Wednesday over whether Goldstein should be tried again for the murder, his mother sat quietly and listened, dressed in a black pantsuit and raincoat, her face, like her son’s, framed by glasses and short, silver hair.

“It was quite a shock,” the elder Goldstein said afterward, leaning on a cane in the courtroom hallway. “I had never seen him with gray hair. He looks exactly like his older brother.”

It was the first time she had seen her son since he left Topeka, Kan., for California in the mid-1970s. Stubborn in his insistence on his innocence, Goldstein for 24 years had been adamant that no one from his family visit him behind bars.

“Once his grandmother came to visit him,” said Geri Goldstein, “He was very upset. He cried. He just felt it was so terribly degrading.”

This time, Goldstein appeared to beam as he caught sight of his mother in court.

The last time around, the trial had been quick.

Thomas Goldstein was living in a garage in a transient neighborhood, attending college, fresh from a stint in the Marines in Vietnam. McGinest was shot down near the apartment. Police arrested Goldstein and he was charged with murder.

There was no physical evidence to tie him to the killing. But a man who had briefly shared a cell with him at the Long Beach city jail, Edward Fink, testified that Goldstein had confessed to him one night. A second man, Loran Campbell, said he had seen the killer run past his window and that Goldstein was the man.

“It just seemed like no time at all that he was sentenced,” Geri Goldstein said. “He kept insisting nothing was going to happen. I even spoke to the lawyer, who said there was no reason to come out.”

Then her son called and told her the bad news: He was going to prison for 27 years to life. But he was sure it all would be reversed soon. “He was primarily concerned about me,” she said. “I was hysterical.”

He forbade anyone to visit him in jail, but Goldstein wrote his mother regularly, and she sent him a portable typewriter. His first job was as a janitor, which gave him access to the library and its law books. Thus began a long, obsessive quest to vacate his conviction.

Late last year, that quest finally appeared to be paying off. A federal appeals court ruled that prosecutors had violated Goldstein’s rights. Fink, it turned out, was a police informant who had testified in a secret deal to get a lighter sentence. Campbell, the judges said, had expressed doubts about his identification of Goldstein and had been improperly coached by police. Defense lawyers had been told nothing.

Goldstein refused overtures from prosecutors suggesting that he could be released if he pleaded guilty to lesser charges. Geri Goldstein guesses he got the stubborn streak from her. “I’m quite a stubborn person,” she said. “Once I make up my mind to do something, I do it.”

Last month, the Los Angeles district attorney’s office decided to try Goldstein again for murder. Wednesday’s hearing was the next step in the process of bringing the case back to court.

Fink and Campbell are dead. Prosecutors will not try to reuse the testimony of Fink, who has been heavily discredited. At Wednesday’s hearing, they said they plan to call Campbell’s stepson and ex-wife, saying the two can back up the original identification of Goldstein as the killer.

The proceedings were over in half an hour. Goldstein went back to jail, pending another hearing March 3, and his mother back to her hotel room in Long Beach. She will line up today for visiting hours at Men’s Central Jail in downtown Los Angeles.

There will be much to catch up on. Her son’s time as a free man in California -- about four years, according to court testimony -- is a black hole to Geri Goldstein.

“It’s funny, I can remember when he was in school; I can remember his bar mitzvah, and when he was in the Marines,” Goldstein said in a telephone conversation before leaving Topeka for her son’s hearing. “I can’t recall much of the California time at all.”

Thomas Goldstein was born in Houston, the second son of Art Polanko and the former Geraldine Havens. But the marriage was on the skids even as Geraldine, known as Geri, waited out her pregnancy.

She left her husband, and a year later married Lawrence Goldstein. The family stayed in Houston until Thomas was a teenager and there were four children, then moved to Kansas City, Kan.

It was a strict upbringing, down to firm adherence to Shabbat dinner on Friday nights. “I can remember him out of breath, trying to get home on Friday night for dinner, because I insisted they be home for Friday night dinner and then services,” Geri Goldstein said.

Thomas Goldstein joined the Cub Scouts and eventually became a Sea Scout, she said. He loved sailing and swimming, and passed Kansas City’s grueling lifesaving course. He came to identify heavily with his stepfather, an ex-Marine. So it was no surprise that Tom chose the Marines after graduating from Shawnee East High School in 1967, she said.

“We couldn’t really afford to send him off to college, and he thought going into the service would help him out,” she recalled.

Before he left for the Marines, Tom took a year and a half to quell his wanderlust. Like many of his generation, he headed for California, hopping into the Triumph TR-3 his parents had given him. At least one point on his itinerary was Downey, Geri Goldstein recalled. That’s where his biological father, a man he had never known, lived.

It was not a Kodak moment, Geri Goldstein said of her son’s reunion with Polanko, who has since died. She said she would rather let the memory die.

But the trip west, and a stint at basic training in Camp Pendleton, seared California’s sun-drenched coast in Tom Goldstein’s memory, his mother recalled.

When he returned from Vietnam, he hung around Topeka, working in his parents’ warehouse business, but he soon grew restless and headed west again, sometime around 1976, she said.

“He hated the winter months after being overseas in the heat,” she said. “He decided he wanted to be someplace warm. So he went to California.”

Court records show that Thomas Goldstein attended Long Beach City College sporadically, spending most of his time alone in a cheap apartment in a transient neighborhood, drinking heavily and living off veterans benefits.

His mother knew of none of this -- not even his arrests for public drunkenness and disturbing the peace while he lived in Long Beach.

“We stayed in touch,” she said. “He would write, let me know about his grades and how it was going along.... He was so busy working at any job he could get, and then with school, that he didn’t have much time for friends.”

She knows little of his son’s life in California, but with a mother’s faith, she remains convinced he is innocent of murder.

“There wasn’t even any circumstantial evidence,” she said. “There was nothing.... He was going to school, working. He didn’t have enough time to get into such trouble.” Plus, she said, “He wasn’t that stupid.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.