Searching for Lessons in Jefferson High Melee

- Share via

They had been milling around for an hour in the sun, 2,000 restless, agitated teens packed onto Jefferson High’s football field, waiting for the earthquake drill to end and lunch to begin. When the bell rang they rushed the gates, shoving, elbowing, knocking classmates aside.

In the crush, two black girls began tussling over a cellphone or a boy, or maybe a boy’s cellphone.

As school police officers dug them out of the center of a heckling crowd, a Latino boy launched a milk carton across the quad. It landed in a group of black football players.

“Who threw the milk carton?” one demanded, confronting the Latino boys.

“Go back to Africa!” was one shouted response.

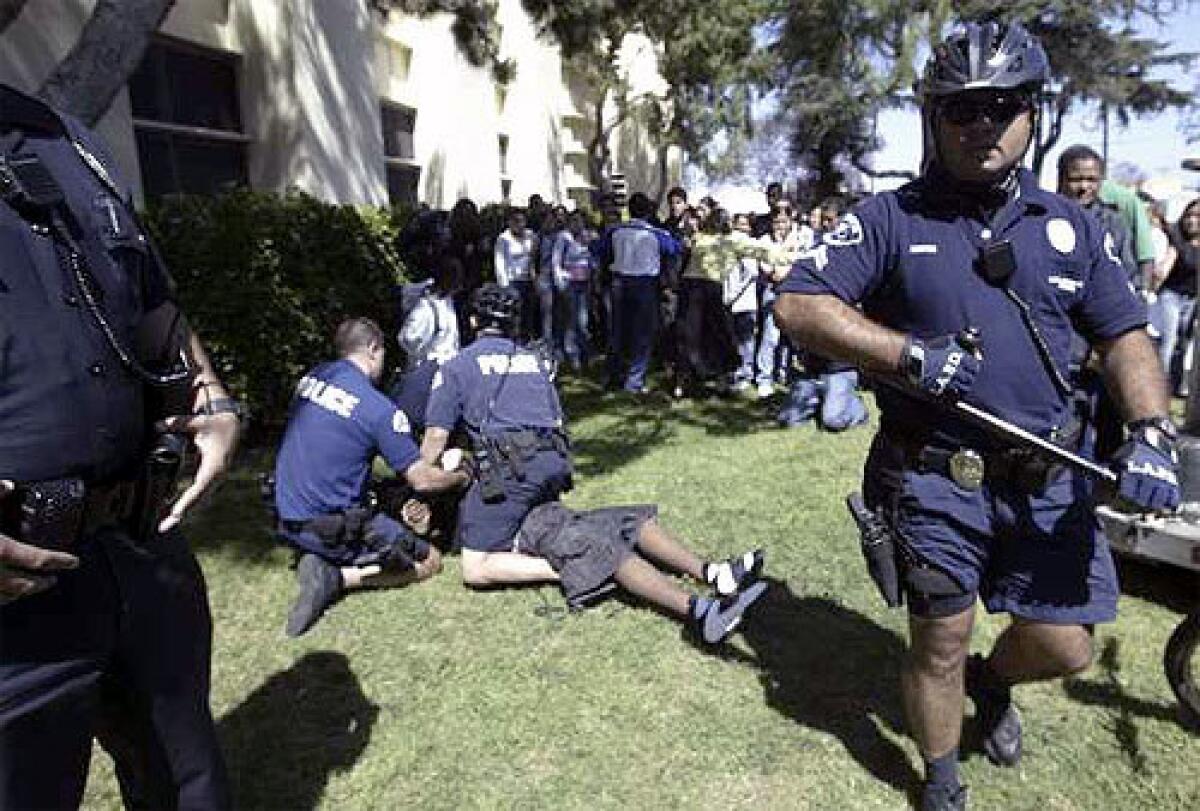

The entire quad erupted in fights.

In that brief moment, a food fight became a race riot. And in the days and weeks that followed, racial skirmishes on this and other Southern California campuses unmasked a current of racial tension that has alarmed law enforcement and school officials.

The Jefferson fight was over in less than 20 minutes. But for two months after that April 14 battle, Jefferson’s black and Latino students faced off in spontaneous skirmishes, orchestrated beatings and at least two more large-scale melees. Twenty-five students were arrested, three hospitalized and dozens suspended or transferred. Hundreds more stayed away from classes, and those who showed up did so with fear.

“I’m scared even to go to class,” said 16-year-old Keiana Scott, as she stood on the lawn outside school a few days after the second lunchtime brawl. One of only about 300 blacks among the school’s more than 3,800 students, Keiana warily eyed a passing group of Latino schoolmates. “I’ve got to look over my shoulder every five minutes to see if somebody’s about to whup me,” she said.

No Single Cause

The unrest comes at a time when Los Angeles has emerged as a national symbol of racial cooperation. A coalition of black, Latino and white voters in May elected Antonio Villaraigosa, Los Angeles’s first Latino mayor since the city’s pioneer days.But the confrontations between blacks and Latinos, which have struck campuses from the South Bay to the Inland Empire and Antelope Valley, suggest that stubborn cultural differences, racially charged gang feuds and social and economic competition can combine to cleave Southern Californians along unexpected racial lines.

“This is not just at one school, and it’s not just kid stuff,” said Khalid Shah, whose Stop the Violence Increase the Peace foundation has been working for years to broker truces between warring black and Latino gangs in the Inglewood area.

“There’s a rise in community violence as it relates to blacks and Latinos, and that is seeping into our schools. When you start seeing large groups of one race fighting against a group of the other race, we can’t, as a city, afford to ignore it.”

“You can’t blame [the fights] on any one thing,” said Ron Rubine, a counselor at Carver Middle School in South Los Angeles, which has had its share of black-Latino conflict. “For some kids, it’s a race thing, for some it’s a gang thing, for some it’s a boredom thing, for some it’s just loyalty to friends.

“Is it really that different with adults? If there was a fight among the staff, we’d align ourselves with the people we hang around with . We have our public face, but look at what we do in private — the way we gossip, the things we say about other people, other groups. We look at these kids and say, ‘What savages!’ but we all have onus in this thing.”

Rapid Escalation

A close look at the first Jefferson fight shows how racial tensions can quickly balkanize a campus — even one where peacemakers outnumber troublemakers.Steve Bachrach teaches in the school’s Film and Theater Academy, a self-contained “small learning community” on campus. He was in his classroom with students when the quad fight began.

A student ran past the room yelling, “Food fight!” Bachrach shrugged it off. But a few minutes later another kid shouted, “Race riot — brown on black!” and several of his students bolted. Outside, Bachrach saw half a dozen kids scaling the school’s chain-link fence, desperately trying to escape from campus.

Bachrach headed for the quad to retrieve his students and found one, a black girl, in a standoff with three Latino boys. She had been beaten and was in obvious pain. He ushered her back to class, where a group of her Latina classmates, all juniors, gathered to console her and press for details. “I was jumped by a bunch of Mexicans,” she said. The group, almost all of them Mexican immigrants, brushed the expletive off as anger speaking.

But across the room, a group of younger Latinas bristled. They strode over, and one angrily challenged the black girl: “Why are you disrespecting me?”

The older girls quickly intervened, ordering the others to back off. The younger girls retreated, but not before belittling their Latina classmates for having “no pride in your own people.”

In the months since that first lunchtime fight, many others faced the same brutal choice: “race pride” came to trump friendships, common interests and personal history.

“Basically, I guess you can say that you had to pick sides. It was just a must,” said Yessinia Rivas, 18, a senior who has since graduated.

Her worried parents gave her advice she didn’t expect: For your own protection, they said, stay away from other people. Her Latino friends demanded she declare allegiance. “Either you were with them or against them,” she said.

Pressure From Peers

In an essay for the independent teen publication “LA Youth,” an anonymous Latino student described being drawn into the initial fight by friends’ demands that he “stand up for my family, my Mexican ancestors, and the people who worked hard so I could be here — my heritage that I’m really proud of.”“I felt good defending my race,” he wrote. “I was hitting anybody I could get my hands on . Many of my friends who knew I was involved in the fight asked me, ‘Aren’t you proud that our people are at war with the blacks?’ Because of that fight, I lost many friends who are African American. The whole tension between Latinos and blacks is changing the way we all think about each other.”

The lunchtime crowd at Jefferson, as at many high school campuses, typically divides by race. Latinos, who constitute nearly 92% of the student body, take the tables on the small, covered patio and gather in groups on the grass. Black students, about 8% of the student population, lounge along a low stone wall between the student store and the science building.

That kind of separation, long chronicled in post-segregation schools, doesn’t necessarily signal trouble. For adolescents, membership in a “tribe” can provide a sense of belonging.

“It only becomes destructive when the groups are seen as rigid and self-enforcing,” said Allan Kakassy, a teacher at Granada Hills Charter High School who has spent 37 years helping district officials develop tolerance programs.

Before the fights, “everybody was having a great time,” said Eric Johnson, 17, president of Jefferson’s Black Student Union. The school’s student leadership group played music at lunch every Friday. “It was like our 20-minute party,” Johnson said.

After the fights, students were so wary that some blacks were afraid to turn their backs on Latinos, and some Latinos avoided the student store, because getting there meant walking past blacks.

“Everything that has been said about the school is not the way it seems,” said Cindy Jaramillo, a 17-year-old senior bound for UC Berkeley. She was on a visit to the college when she saw news of the disturbances on a dorm television. She had never thought of her campus as racially divided. “There was no problem,” she said. “There was fighting and everything, but I think that happens at every single school. The riots turned things the other way.”

Gangs Sow Fear

Race became a factor in even the simplest endeavors. When school administrators banned white T-shirts because of the style’s popularity with gangs, scores of Latino students showed up wearing brown T-shirts instead. “It was saying that we’re here and that we have pride in each other and we’re not going to let nobody talk stuff about us,” said Daniel Rios, 14, wearing a brown T-shirt that hung to his knees. Black students struck back by wearing black.Bachrach considered the “brown pride” display an act of intimidation, whether deliberate or not. “It was a direct threat to another population on campus. And that’s not tolerable,” he told his students. He followed up with a letter to their parents, explaining the racial dynamics of clothing selection.

At Jefferson — a chronically overcrowded and underachieving campus, set in a poor, often violent neighborhood — outside forces exert their own pressures. Some link the school’s racial problems directly to an ongoing war between Latino and black street and prison gangs.

One of the area’s largest gangs, 38th Street, is affiliated with the powerful Mexican Mafia prison gang, say Los Angeles Police Department Newton Division officers. The Mexican Mafia has spent more than a decade trying to control the drug trade from behind bars, in part by directing Latino gang members to target blacks with shootings, beatings and harassment, according to law enforcement sources and imprisoned gang members who spoke with The Times.

Police have not tied the gang directly to the campus unrest, but fear of gang retaliation is so strong among students and parents that most interviewed by reporters refused to let their names be used.

Two years ago, according to parents and an injunction by the Los Angeles city attorney, the 38th Street gang so dominated Ross Snyder Park, a few blocks from Jefferson, that a Pop Warner football league run by black parents moved its practices to the high school’s football field.

Racial tension heightened noticeably this spring, when word spread across the city that Latino gang members were plotting a Cinco de Mayo massacre of blacks in retaliation for a drug rip-off by a local black gang. According to the rumor, a Crips gang had stolen a huge cache of cocaine from Florencia 13, a large Latino street gang active in the Jefferson area. Versions spread through the Internet, sparking such citywide fear that more than 51,000 children stayed away from Los Angeles Unified schools that day.

Parents Can Have Effect

The rumor contained a grain of truth. Los Angeles County sheriff’s investigators believe that in the summer of 2001, the East Coast Crips stole a truckload of cocaine, estimated at 300 kilos, belonging to Florencia. The theft ignited a gang war that still rages, said Sheriff’s Sgt. Morrie Zager, who heads the department’s gang unit in the Century Division.But Zager said investigators found the Cinco de Mayo threat baseless.

“We’re in the Internet age, where every teenager is online, even the thug teenagers,” he said. “We didn’t find anything credible to any of that stuff — and believe me, we tried to substantiate anything we could.”

Still, students and parents from Long Beach to Palmdale to Moreno Valley continue to cite the drug-theft rumor to explain campus racial tension.

“I feel like my son has a target on his back,” said the mother of a black Jefferson student who was suspended for fighting with a group of Latinos he said jumped him as he left class.

“I told my son, don’t start nothing, but if they pick with you, don’t back down. It sounds simple to walk away, but it’s not that simple. If you do, you will continue to [have to] run. So you have to fight.” She shrugged. “It sounds terrible, but that’s the way society is.”

Many teachers and school officials say parental attitudes often prime students for friction. Tensions are particularly high between blacks and newly arrived immigrants in the neighborhoods surrounding Jefferson, once a center of black culture and pride.

The school reflects the changing demographics of inner-city Los Angeles. In 25 years, the student body has gone from 31% Latino to 92% Latino. More than half of Jefferson’s Latino students are immigrants, most of them from Mexico, where only 1% of the population is black. During the 1990s, the black population of Jefferson’s attendance area declined from about 34,000 to less than 22,000 while the Latino population, mostly recently arrived Mexicans, grew from 105,000 to 121,000, according to the U.S. Census.

Cultural Differences

In the United States, rural Mexican immigrants often come face-to-face with black people for the first time.In their home country, racial stereotyping is more open and less challenged. Mexican President Vicente Fox ignited a furor here in May with a comment that Mexicans who emigrate to America do work that “not even blacks want to do.” And last week national black leaders and the Bush administration condemned a series of postage stamps released by the Mexican government featuring a thick-lipped black comic book character reminiscent of Amos and Andy.

In the neighborhoods around Jefferson High School, blacks and Mexicans live next door to each other, but — separated by language, culture and history — they rarely interact. Immigrant children navigate a confusing cultural milieu, where black youths can throw the N-word around, but their Mexican friends aren’t allowed to use it, and popular brands of hip-hop clothing are considered off-limits to all but blacks.

Mexicans living in largely black areas tell of being robbed, beaten and intimidated by blacks. Their black neighbors complain about chickens in the yard, old cars on blocks and harassment by belligerent street toughs allied with Latino gangs.

Among parents — often exhausted and embittered by economic stress — race has become the prism through which every gesture is viewed.

A Latino mother says it doesn’t matter that blacks on the campus are vastly outnumbered: “They’re bigger, stronger they’re hurting our boys.”

A black mother complains that after one fight, when the combatants sweltered in a hot room waiting for police, “a teacher came in and gave the Latino kids water, wiping their faces with towels. Not one time did she reach over and give any of the African American kids anything.”

Listening to their stories, “it’s hard to tell who is the prey and who is the predator,” said Phil Saldivar, the district administrator investigating the fights, who was sent to Jefferson to help restore order. “The blame depends on who you speak with and what perspective they’re bringing.”

Those perceptions give race counselors plenty to combat.

A Latino girl staying after school for a human relations meeting complained to a black mediator that “the blacks are always whining about slavery. They don’t want to do nothing to better themselves.” Her friends murmured their assent.

A few days later, a black girl waiting for a ride home from school with her mother blamed the racial problems on “too many Mexicans who can’t even speak English.” They gossip in Spanish and poke fun at blacks, she said.

Jefferson’s students come from neighborhoods with some of the city’s highest rates of crime, homelessness and teenage pregnancy. There are few jobs and even fewer recreation outlets.

Among Los Angeles Unified’s 49 high schools, Jefferson had the second highest number of major crimes in its attendance area — 94 homicides, more than 2,700 robberies, and about the same number of aggravated assaults from 2002 through mid-2004, according to a Times analysis of LAPD data for that period.

Education Suffers

Accustomed to apathy among students, teachers say they have been shocked by the physical and emotional ferocity of this spring’s fights. One recounted seeing a Latino boy dragged from his car by blacks and beaten in front of his mother. Another told of a black special education student chased from his classroom by a group of Latinos, who pummeled and kicked him when he fell.One teacher stepped in to help a boy beaten unconscious in a fight on a sidewalk near campus. Students watching the beating seemed unmoved, she said. “It changed me. For days after that, I had to duck into the bathroom or a classroom to cry. I realized some of our kids see things like this on a regular basis. No wonder our test scores are in the toilet.”

Jefferson Principal Norm Morrow — who was reassigned as the fights raged on — said he had no idea emotions on campus were so volatile. “This thing happened so quickly, it caught us off guard,” he said. “Had we seen signs of intolerance damn right I would have done some things differently.”

Morrow wanted to shut down the school after the first brawl, “just for a brief period of time to settle things down,” he said. But Supt. Roy Romer refused, concerned that canceling classes would set a terrible precedent and amount to a public admission that school officials had lost control.

Changes Underway

The school has tried to stop the cycle of fights with a flurry of community meetings, increased police presence and student dialogue. The lunch hour is now divided so only 1,000 kids are on the quad at a time. New security cameras will be installed and students will be required to wear uniforms. A new principal was brought in from East Los Angeles. Human relations experts, including ex-convicts, former gang members and representatives of the U.S. Justice Department, frequently visit campus.The Los Angeles School Board is considering restoring its office of intergroup relations, which provided guidance to schools struggling with racial issues. It was eliminated five years ago in a round of budget cutting.

For now, Jefferson officials say calm has returned to campus.

Many of those arrested or disciplined for fighting have been transferred. Others were pulled out by parents or simply disappeared.

“It’s a handful of knuckleheads causing the problem,” one school police officer said. “Most of these kids don’t hate each other. It’s just, ‘You jump off; I’ll jump off.’ We’re getting rid of the hotheads.”

But some say school officials are simply shifting the problems.

“So they’re not going to be killing each other at school, just on the streets,” said Chico Brown, an ex-gang member who helps run A Place Called Home, a community center a few blocks from Jefferson.

“They need to be taught to value each other,” he said. “They have to live together.”

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

School in transition

Jefferson High School, south of downtown Los Angeles, draws its enrollment from a community that has dramatically shifted over the past three decades from black to Latino. Latin American immigrants, mostly from Mexico, have been coming in growing numbers and now make up about half the population.

Population figures for 2003-04

--

Jefferson High School

Latino: 3,547

African-American: 305

Other*: 17

--

LAUSD

Latino: 541,514

African-American: 88,271

Other*: 117,224

--

* Other includes white, Asian, Filipino, Pacific Islander, American Indian and multiple or no response.

Sources: California Department of Education, Los Angeles Unified School District, U.S. Census Bureau, ESRI, TeleAtlas. Data analysis by Doug Smith

Times staff writers Joel Rubin, Sam Quiñones and Doug Smith contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.