Nerves on a hair trigger in Marine patrol

- Share via

Reporting from Near Spin Ghar, Afghanistan — The bearded man stopped his battered Toyota near the Marine walking point on patrol. The man left his vehicle, smiling and calling out to half a dozen other Marines in tones that were friendly but with words that were incomprehensible to anyone without a knowledge of Pashto.

At the same time, a small boy riding a donkey approached the Marines from the other side, looking at the man as if for directions.

The confluence made the Marines doubly suspicious. They had been warned that suicide bombers might walk or drive up to Marines and that such bombers might use children as decoys.

“Stop there!” shouted a Marine as others in the patrol dropped to an alert position, their M-16 rifles at the ready.

Suspicion is ever present with the Marines in Helmand province, where sympathy for the Taliban is strong and the sudden U.S.-led offensive in Marja has propelled residents into face-to-face contact with thousands of foreigners bristling with weapons.

In the course of the 4-day-old assault, two Afghan civilians, both men, were killed by troops when they approached coalition forces and failed to heed warnings to halt, Western military officials have said.

Even in the most bucolic of settings, the Marines of Bravo Company, 1st Battalion, 3rd Regiment are keenly aware of the surrounding dangers.

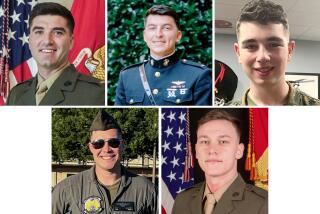

Two Bravo Marines -- Lance Cpl. Timothy Poole, 22, of Bowling Green, Ky., and Lance Cpl. Jacob Meinert, 20, of Fort Atkinson, Wis. -- were killed in January in separate roadside bombings while on foot patrol.

Poster-sized pictures of the two, which had been displayed at their memorial services, are on the wall outside the company communication center as a daily reminder that death is always near.

As the Marines on patrol stared at the man and the boy on the donkey, the thump of artillery pounding at Taliban positions in Marja rumbled in the distance. The air was still and clean, no sign of the late-afternoon dust storms that are common and can serve as perfect cover for Taliban moving into position.

“Stop there!” shouted a second Marine, putting up his left hand, palm outward, his right hand on his M-16.

As the Marines’ focus sharpened to a razor point, the nearby sounds of farming provided a dissonant soundtrack: the chugging of tractors, the grinding gears of trucks loaded with chaff, the bawling of sheep and cows.

The man’s voice got louder as he approached, and he began to wave his arms.

This patrol was meant to “show presence” along dusty and gravel-strewn streets adjacent to a canal clogged with a greenish sludge. The troops were supposed to wave to residents, tousle the hair of children, show the Afghans that the Americans were there to protect them.

But when suspicion takes hold, everything has a sinister tone.

As the Marines walked, they had seen several men with shovels squatting near a bend in the canal.

Were the men planning an attack or looking for a place to plant roadside bombs, like the ones that killed Poole and Meinert? Or were they talking about joining a U.S.-led effort to clean the irrigation canals and boost production of corn and wheat, so that farmers are not tempted to plant the poppy crop that turns into heroin?

The Marines radioed company headquarters to report the approach of the man with the truck.

“Is there an interpreter present?” asked a radio operator.

“Hey, I’ve got one with me,” answered a Marine.

The interpreter, who had come along to help the troops negotiate with shopkeepers for eggs, orange soda and stone-baked bread, spoke to the man. His demeanor had changed, reflecting some of the suspicion aimed at him.

“He’s OK. He just wants to talk about projects with Capt. Tom,” the interpreter said, referring to Capt. Tom Grace, 33, the New Jersey native with a liking for steamed rice and country and western music. He’s the commander of Bravo Company.

The information about the man’s intentions was relayed back to headquarters. Grace knew the man, considered him influential and was willing to meet with him.

The man was waved on. Grace would meet him just outside the small base, where gun towers, concertina wire and rock barriers separate the troops from the villagers.

The boy sharply tapped his donkey with a stick and continued down the path.

“I’m glad we were careful,” said Lance Cpl. Jean Sebastian Lajeunesse, 21, a Canadian emigre who joined the Marine Corps as a way to show thanks to his adopted country.

“Afghanistan is different than America,” he told a younger Marine. “You have to remember that.”

Earlier, Grace said writing letters to the families of Poole and Meinert after their deaths was the most difficult thing he’s ever done as a Marine.

Yet he believes that foot patrols are essential. It’s hard to win over the populace when you roll by in an armored vehicle topped by a machine gun.

The patrol from Bravo Company resumed its slow march, hoping to win hearts and minds but also with a deep desire to avoid the fate of Poole and Meinert.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.