Seasonal affective disorder increasingly a workplace issue

- Share via

Reporting from Chicago — Since she was hired two years ago as a medical assistant, Jennifer Simonsis has come to an agreement with her employer: During the winter, she gets time off to see her doctor, frequent breaks and help in setting up a light-therapy lamp at her desk.

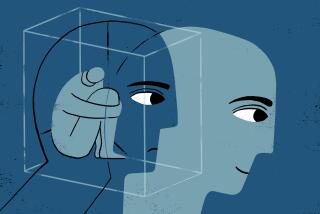

Simonsis gets workplace accommodations for seasonal affective disorder, or SAD -- depression triggered by limited daylight in winter.

Pointing to a federal law that prohibits employers from discriminating against the disabled, some SAD sufferers say they are entitled to schedule changes, access to windows and other modifications. Recent legal rulings are prompting human resources experts to warn about the need to take the depression seriously.

“Some people brush you off, saying you’re just in a bad mood this time of year,” said Simonsis, 36, of Mount Prospect, Ill. “But it’s a real disability, and employers need to realize that.”

Most people experience gloominess in winter, but for some the psychological and biological symptoms are much more serious.

The U.S. 7th Circuit Court of Appeals in Chicago ruled in October that a teacher could pursue a lawsuit against her former employer alleging that the school district had failed to accommodate her SAD, causing her mental health to deteriorate.

“I think seasonal affective disorder is rare, but it’s protected under disability law,” said Chicago lawyer Gerald Maatman Jr., who represents employers in workplace disputes. “The law protects a wide range of conditions, not just physical disabilities like heart attacks and carpel tunnel.”

When Employment Law Today, a publication put out by the New York-based Alexander Hamilton Institute, ran an article about the recent appeals court ruling, describing symptoms of seasonal affective disorder and explaining that accommodations may be necessary, editor Gloria Ju said she was dismayed to receive an e-mail from a manager brushing it off.

“She scoffed about seasonal affective disorder, saying that everyone feels down in the winter,” Ju said. “But . . . seasonal affective disorder and other forms of depression are not made up and need to be taken seriously.”

The depression is often triggered around October and lifts in March. Fatigue, declining sexual interest and weight gain are other common symptoms. Treatment includes antidepressants, therapy and exposure to intense lamps that simulate natural light.

No one tracks how many people seek workplace accommodations for SAD or other disabilities. But the number of discrimination complaints filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission related to anxiety, depression and other psychiatric disorders nearly doubled between 2005 and 2009. Last year, 3,837 such complaints were filed nationwide.

Renae Ekstrand, 49, whose lawsuit led to the appellate ruling, said her teaching went smoothly for years until the fall of 2005, when she was assigned to a basement classroom with no windows.

She explained to the Somerset School District in Wisconsin that she suffered from seasonal affective disorder and that her depression would be worsened in such conditions. But her pleas for a classroom with windows were dismissed, despite notes from her doctor, according to the court ruling.

Within months, Ekstrand was suicidal. She quit rather than endure the basement classroom.

The school district declined to comment on the case, which is headed back to federal court in Madison, Wis.

Ekstrand, who now teaches early childhood education at South Dakota State University, said she was heartened by the appellate ruling and was determined to see the lawsuit through.

“It’s been very stressful for me and my family,” she said. “But it’s important for people to see seasonal affective disorder for what it is, and for school districts and other employers to know that they have to take all types of disabilities seriously.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.