Ireland approves European Union fiscal treaty

- Share via

LONDON — Irish voters approved a European treaty to keep government spending in check, offering a small victory Friday to the region’s leaders as they battle a worsening debt and banking crisis that has raised fear for the survival of the euro.

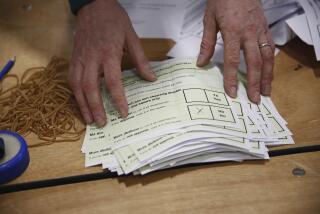

A referendum to adopt the fiscal pact won by a strong margin, 60.3% to 39.7%, though only about half of Ireland’s voters cast ballots Thursday. Prime Minister Enda Kenny, who campaigned hard for the “yes” side, hailed the result as a signal that his bailed-out nation “is serious about overcoming its economic challenges.”

“This treaty will not solve all this country’s problems, but it is one of the many foundation stones that you need to put in place to ensure that our economic position stands on firm ground for the future,” Kenny said soon after the official tally was announced Friday afternoon.

Yet even as he spoke, stock markets around Europe continued their heavy daylong slide in reaction to weak jobs data out of the U.S. and to Europe’s inability to keep a lid on its debt crisis. All eyes are now fixed on Spain, whose tottering banks and tanking economy have fueled concern that it will become the next Eurozone country to seek international aid, after Greece, Ireland and Portugal.

A “no” vote in Ireland probably would have increased investor anxiety over government indebtedness, and so there was some relief in European capitals that the obstacle had been cleared.

But critics also noted that a new European Union treaty to enshrine future budgetary discipline does nothing to address the immediate problems engulfing the region, such as low economic growth and widespread joblessness. Figures released Friday showed that, in the 17 nations that share the euro currency, the unemployment rate remained at a record 11% in April.

Borrowing costs for Spain and Italy are now flirting with the intolerably high levels that eventually drove Greece, Ireland and Portugal to ask for international rescue packages. And depositors are pulling their money out of financially ailing countries at a quickened pace, raising the specter of catastrophic bank runs.

In an unusually stark warning, the EU’s top economic official said Friday that without faster, more drastic action by leaders, the Eurozone risked falling apart, which would destroy the biggest symbol of European unity.

“We face either a gradual degeneration of the euro area or a strengthening of Europe’s basis, that is, the economic union,” Olli Rehn, the EU’s commissioner for economic affairs, said in a speech in Helsinki, Finland.

The treaty to rein in spending is supposed to be one step toward greater integration. But illustrating how slowly the wheels turn in the EU, only a few the 25 countries whose leaders signed on to the agreement half a year ago have actually gotten around to ratifying it. Not even Germany, its most ardent backer, has yet done so. Meanwhile, fast-moving markets are pressing some countries into a corner.

The pact obliges countries to keep their budget deficits to 3% of gross domestic product or less and caps the amount of government debt they can rack up. Breaching the rules can result in heavy fines.

Only Ireland has put the accord to a popular vote.

The campaign argued that approval was vital for the country’s continued participation in the EU and also for access to bailout funds. Some analysts predict that Ireland, where a real-estate bubble and banking collapse drove the economy into a deep hole, will have to ask for another rescue package on top of the one it received a year-and-a-half ago.

But opponents warned that Ireland was surrendering some of its hard-won sovereignty. They also object to the punishing austerity cuts that Ireland has imposed in exchange for being bailed out by its European partners and the International Monetary Fund.

“I want to remind the government that in the course of this campaign … they committed to jobs [and] growth,” lawmaker Gerry Adams told Irish television. “Many of the ‘yes’ voters from my own constituency told me that they’d voted yes through gritted teeth. So we’ll be holding the government to the commitments that they made.”

By contrast, in Greece, the leftist leader who has roiled the political scene reiterated his pledge Friday to renege on Athens’ commitments to its international creditors if he wins power in elections June 17.

“The first act of a government of the left, as soon as the new Parliament is sworn in, will be a cancellation of the bailout and its implementation laws,” said Alexis Tsipras, leader of the Syriza party.

The political instability in Greece since an inconclusive elections May 6 has heightened concern that the Mediterranean nation could be forced to exit the Eurozone. Tsipras insists that his country can scrap its bailout agreement and still remain a Eurozone member, but other European leaders say that the two goals are incompatible.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.