A tall stand for property rights in China

- Share via

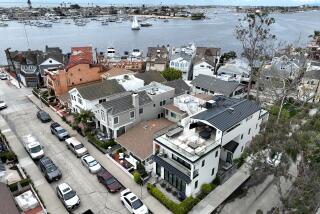

BEIJING — The photograph says it all.

A frail-looking brick house clings to a small mound of earth surrounded by a giant pit dug by menacing bulldozers.

They call it the “nail house.” The name refers to the owners’ uncanny ability to defy developers’ plans to demolish it to make way for a luxury apartment and shopping mecca.

The standoff in central China’s Chongqing municipality is nothing new. Government-backed development projects have been eating up private homes across the country, creating a wave of resistance as millions of residents are uprooted, with many complaining of unfair compensation or forced removal.

But since the National People’s Congress passed landmark legislation two weeks ago to protect private property rights, the nail house seems to have become a rallying point for a nation eager to see whether its communist leaders will pay more than lip service to what many see as a basic human right.

“History will remember this picture,” one blogger wrote next to one of many images of the nail house splashed across cyberspace and an increasingly dynamic Chinese press.

“They should leave this house standing as a monument to the Chinese people’s struggle for property rights,” said Zhou Xiaozheng, a sociologist at People’s University in Beijing.

The defenders of this forlorn outpost are a folksy couple some have likened to cult figures in classic kung fu movies. As it happens, Yang Wu is a martial arts champion skilled in the ways of the fist. He has left much of the public speaking to his wife, Wu Ping. The stylishly dressed woman sometimes refers to herself as Peking Opera character Aqing Sao, an underground Communist Party cadre masquerading as a teahouse matron known for her wit in outsmarting the enemy.

For the last three years, Wu and her husband have managed to fend off developers as each of their 280 neighbors surrendered their homes to the wrecking ball.

“People must live with dignity,” she said, her voice sounding hoarse and tired over the telephone line. “If you are right, you must stand up for yourself and not allow your rights to be trampled.”

According to Wu, the family house was originally built on the site in 1944. Her father-in-law ran a grocery store there and passed the property on to his son. In 1994, the couple rebuilt it from scratch. Since then, they have used it to run several businesses, including a restaurant and a karaoke parlor.

“They say the houses on our street are dilapidated,” Wu said. “After we rebuilt ours, it looked better than many storefronts in big cities like Beijing. The fact that it’s still standing after all the abuse it suffered from the demolition all around us is a testament to its quality and durability.”

Housing authorities told state media that the relocation order is legal and that the couple had been offered an adequate compensation package. Instead, they wanted a lot more money, to pay for a residence of the same size, on the ground floor and facing the street, like their current house, the authorities said.

Wu said the government was trying to discredit her by making her sound unreasonable.

“The fact is what they are offering us is way below market price and we cannot accept that,” she said.

Observers say such disputes are inevitable because China lacks an independent appraisal system. Local governments eager to promote growth tend to side with developers and fast-track projects.

“It becomes a free bargaining process without strict standards,” said Lou Jianbo, a property law expert at Peking University.

A local court recently issued an ultimatum to vacate the premises. Yang has since returned to the fort even though the couple have not been living there because road access has been cut off, along with water and electricity. He has raised the Chinese flag and vowed to defend his property.

Chinese websites have followed each twist: Yang waving the flag and hanging up a protest banner. Yang hoisting up tanks of gas by rope. Presumably they’re for cooking, although some fear Yang might be saving them for other purposes.

“He’s going to stay there until the end, but I am losing hope,” said Wu, who said she’d been told the house would be demolished by the end of the week. “Power is in their hands. I am pessimistic that the new property law can protect us.”

No matter the outcome, observers say, a new page has turned in the history of the Chinese people’s relationship with private property.

“The nail house spirit will spread among the people,” said Teng Biao, a Beijing lawyer. “In the future there will be more nail houses like this one. The government will have to think twice before striking them down.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.