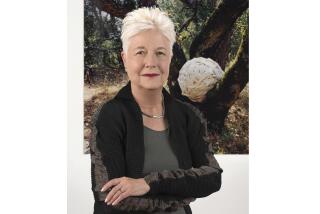

Eleanor Callahan dies at 95; subject of photos by husband, Harry

- Share via

Eleanor Callahan, whose ever-changing image became a sensitively nuanced chapter of photography history — composed of pictures taken over more than 50 years by her husband, Harry Callahan — died Tuesday in an Atlanta hospice. She was 95.

The cause was cancer, said her daughter, Barbara Callahan.

The couple met on a blind date in 1933, when Eleanor was a secretary at Chrysler Motors in Detroit and Harry was a clerk at the firm. They were married three years later, forging a remarkably close relationship that lasted until Harry’s death in 1999 and produced hundreds of imaginatively composed black-and-white portraits.

Often portrayed in the nude, Eleanor is sometimes the central event of a striking picture, filling the frame with her ample contours or rising in Lake Michigan with her eyes closed and her long, dark hair sweeping through the water. In other memorable photographs, she is a tiny but powerful feminine force whose presence fills a landscape or an empty room.

Harry Callahan is known for merging pure photography with experimental techniques in a distinctively personal mode of expression. And none of his work is more personal than the portraits of his life partner and constant muse.

“Eleanor went beyond being Harry’s companion, wife and the mother of his child,” said Stephen White, a longtime photography dealer who lives in Los Angeles. “She was an additional f-stop on his lens. Through her, he saw form and structure more clearly, both in nature and in the world. She was present in his photographs even when she wasn’t in them. Eleanor was Harry Callahan’s collaborator, for she rested inside his psyche.”

Eleanor Knapp was born June 13, 1916, in Royal Oak, Mich. She chose a secretarial career rather than going to college and continued to work as the Callahans moved to Chicago and Providence, R.I., where Harry taught for nearly 20 years at the Rhode Island School of Design. As a young man, he had left Chrysler to study engineering at Michigan State University but dropped out and returned to Chrysler, joining the company’s camera club.

Essentially a self-taught photographer, he said his interest was sparked by a movie camera owned by one of Eleanor’s relatives. Harry considered buying one of his own, but chose a still camera instead and began photographing in 1938. He often credited Ansel Adams with encouraging him to be an artist and teaching him that it wasn’t necessary to travel far and wide to find inspiring subject matter.

In 1980, when Callahan and his wife visited Los Angeles to help launch Light, a photography gallery on La Cienega Boulevard, he told a Times writer: “I just love to photograph. I get up in the morning and I know that’s what I want to do. Why shouldn’t a photographer be like any other workman? Why should he sit around and wait until the sun hits an object in a certain way?”

And why should he search for other models when his wife was willing and close at hand? He began photographing Eleanor in 1941 and gained an additional subject in 1950, when their daughter was born.

Through the years, Harry Callahan had little to say about his photographs. Eleanor said even less. But she was in the public eye in 2007, when curator Julian Cox organized “Harry Callahan: Eleanor,” an exhibition at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. On that occasion, she told an interviewer that she never refused her husband’s requests to pose because of her trust in his vision and love of his work.

In 1996, when a retrospective of Harry Callahan’s work was presented at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, Eleanor was quoted in the Washington Post as saying she “didn’t mind” being constantly on call for photo sessions.

“Heavens to Betsy,” she said in the newspaper, “I was used to it by then. He’d photograph me while I was sleeping. Or he’d just sneak up on me. I never protested. Photography was as much a part of our lives as getting up in the morning. I wasn’t worried about the pictures. I never had any thought that they would be anything but nice. Harry was so intense in his desire to be a photographer, and I thought that was just great.”

Besides her daughter, Callahan is survived by two grandchildren.

Muchnic is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.