W. Mark Felt, Watergate source ‘Deep Throat,’ dies at 95

- Share via

W. Mark Felt, the former FBI official who ended one of the country’s most intriguing political mysteries when he identified himself as “Deep Throat” -- the nickname for the anonymous source who helped guide the Washington Post’s Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation into the Watergate scandal -- has died. He was 95.

A controversial figure who was later convicted of authorizing illegal activities in pursuit of members of the radical Weather Underground, Felt died of heart failure Thursday at his home in Santa Rosa, his grandson Rob Jones said.

FOR THE RECORD:

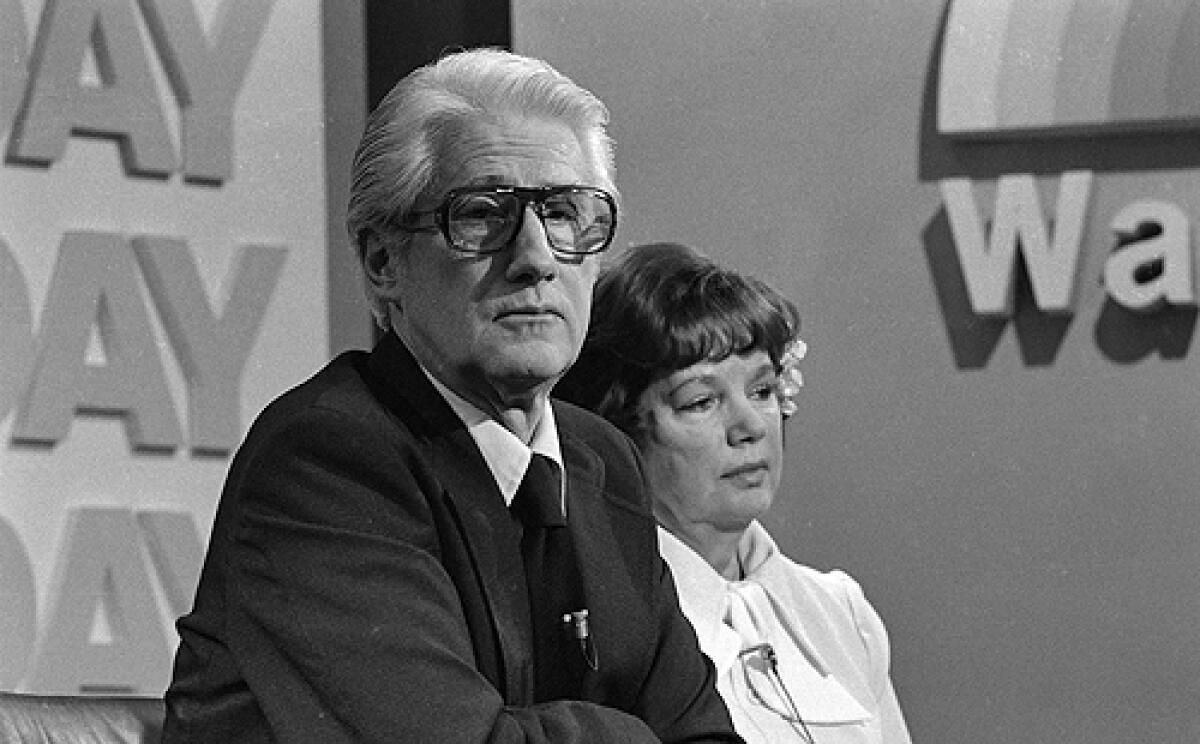

Felt obituary: The obituary of Watergate figure W. Mark Felt in Friday’s California section said that he oversaw background checks at a Seattle plutonium plant. Felt was based for a time in the FBI’s Seattle field office, but the Hanford plutonium plant, where he oversaw the background checks, is in Richland, Wash., about 200 miles southeast of Seattle. Also, a photo caption accompanying the obituary incorrectly gave his name as Mark W. Felt. —

Felt was deputy associate director of the FBI in 1972 when he began supplying information to Bob Woodward, who with Carl Bernstein made up the Post’s investigative duo who doggedly pursued the story of the Watergate break-in and a conspiracy that led directly to President Nixon, who ultimately resigned.

The reporters continued to keep Felt’s name a secret, but in 2005, at the age of 91, Felt told Vanity Fair magazine, “I’m the guy they used to call Deep Throat.”

His disclosure ended a mystery that had intrigued Washington insiders and journalists for three decades and provided the grist for many hotly debated newspaper and magazine articles.

While Felt’s name was raised as a suspect on several occasions, he always managed to deflect attention, usually by saying that if he had been Deep Throat he would have done a better job of exposing the wrongdoings at the White House.

His disclosure in a Vanity Fair article by his family’s lawyer, John D. O’Connor, provoked a national debate: Was he a hero who should be lauded for sparing the country the strain of further high crimes and misdemeanors by the Nixon White House? Or was he a traitor who betrayed not only his president but his oath of office by disclosing grand jury information and the contents of FBI files?

For the most part, reaction is split along political lines.

“There’s nothing heroic about breaking faith with your people,” said commentator Patrick J. Buchanan, a former Nixon speechwriter. Felt “disgraced himself and dishonored everything an FBI agent should stand for.”

But Richard Ben-Veniste, a key lawyer in the Watergate prosecution team, said Felt’s role showed that “the importance of whistleblowers shouldn’t be underestimated, particularly when there are excesses by the executive branch of government -- which in this case went all the way to the executive office.”

Felt’s moment in history began to unfold shortly after five men in business suits were arrested at the Watergate complex in Washington on June 17, 1972, after breaking into the offices of the Democratic National Committee. Nixon Press Secretary Ron Ziegler dismissed the incident as “a third-rate burglary,” but details gradually tumbled out tying the burglars to the president’s reelection campaign. Misdeeds in the White House were uncovered, hearings were conducted in the House of Representatives and the Senate, and for the first time in American history a president was forced to resign.

The relationship that defined a generation in journalism began about 1970 when Woodward was a Navy lieutenant assigned to the Pentagon as a watch officer. In his book, “The Secret Man: The Story of Watergate’s Deep Throat,” published after the Vanity Fair article appeared, Woodward wrote that he met Felt when he delivered a package of documents to the White House and struck up a conversation with him in a waiting room.

From that initial meeting, Woodward cultivated a friendship that would pay off handsomely after he entered journalism. Felt began to provide tips to Woodward when he was a cub reporter at the Montgomery County Sentinel, a suburban Maryland newspaper, and later at the Post, where he was tipped by Felt on stories about the investigation of the 1972 shooting of George C. Wallace, the Alabama governor then running for president.

When Woodward was assigned to the Watergate break-in, he again pressed Felt for help. His request came during a crucial moment in the FBI’s history: Felt’s mentor, the legendary founding director J. Edgar Hoover, had died the month before the break-in, and Assistant Atty. Gen. L. Patrick Gray III had been named acting director. Felt feared -- and his suspicions were later proven right -- that Gray was too close to the Nixon administration to conduct an uncompromised investigation.

He agreed to help Woodward but only on “deep background,” a term meaning that “the information could be used,” Woodward wrote, “but no source of any kind would be identified in the newspaper.”

Felt insisted on using covert rules he had learned while working in the FBI’s espionage section during World War II. If Woodward needed to talk to Felt, he would move a flower pot with a red cloth flag in it to the front of his apartment balcony. If Felt needed to talk to the reporter -- to correct something the Post had written or to convey other information -- he would circle page 20 in Woodward’s home-delivered copy of the New York Times and draw clock hands on the page to indicate the time of the meeting. He resisted telephone contact in favor of clandestine 2 a.m. encounters at an underground parking garage in Rosslyn, Va.

The two met from June 19, 1972 -- two days after the break-in -- to November 1973, five months after Felt left the FBI.

Within the paper, only Woodward and Bernstein knew the identity of Deep Throat, a name borrowed from a notorious pornographic movie of the era. But Felt dealt only with Woodward, and Bernstein did not meet him until 2008.

When Nixon left office on Aug. 9, 1974, the two reporters shared the secret with Post Editor Benjamin C. Bradlee, who until then had only known that the source was a high Justice Department official.

Nixon, according to Woodward, had suspected Felt of being the confidential source and assumed him to be part of a Jewish cabal out to get him. According to Vanity Fair, Felt had no religious affiliation.

Felt repeatedly denied lending any assistance to the Post reporters. At one point, apparently to throw the curious off the trail, he advanced the notion that Deep Throat was a composite of several sources, and for a while that theory gained some traction.

In his 1979 memoir, “The FBI Pyramid,” Felt said, “I never leaked information to Woodward and Bernstein or anyone else.” But the inside jacket of the book noted that Felt was “rumored to be the famous informer Deep Throat.”

As late as 1999, Felt denied it.

“No, it’s not me,” he told the Hartford Courant. “I would have done better. I would have been more effective. Deep Throat didn’t exactly bring the White House crashing down, did he?”

But to Woodward, Felt’s contribution was essential. His “words and guidance had immense, at times even staggering, authority. The weight, authenticity and his restraint were more important than his design, if he had one,” Woodward wrote.

Why Felt put himself at risk to help the Post remains an unanswered question.

In his book, Woodward speculated that his former source “believed he was protecting the bureau by finding a way, clandestine as it was, to push some of the information from the FBI interviews and files out to the public, to help build public and political pressure to make the president and his men answerable.” At the same time, Woodward saw Felt as a conflicted man who was “not fully convinced that helping us was the proper course.”

In the 1976 movie “All the President’s Men,” based on the Woodward and Bernstein account of their Watergate experiences, Felt was portrayed by Hal Holbrook as a man in the shadows, cagey, distrusting and “disturbingly detached, almost as if he’s observing the events with a hollow laugh,” wrote critic Roger Ebert.

If not for the Watergate years, Felt would likely be remembered not as Holbrook depicted him in the movie but as the character Efrem Zimbalist Jr. portrayed in the television show “The FBI.” On the air from 1965 to 1974, the show glamorized the bureau. An unpaid consultant to the show, which had Hoover’s blessings, Felt came to personify the model FBI agent -- buttoned-down, handsome, discreet, all business.

The son of a carpenter and building contractor, Felt was born in Twin Falls, Idaho, on Aug. 17, 1913. When his father’s business suffered during the Depression, Felt took jobs as a waiter and a furnace stoker to pay his tuition at the University of Idaho.

After graduating in 1935, he attended night classes at George Washington University Law School. After earning a law degree in 1940, he was hired at the Federal Trade Commission but found the work tedious.

Friends urged him to apply at the FBI, and he was accepted. After completing 16 weeks of training, Felt was stationed in several field offices before being assigned to the espionage section in Washington to track down World War II spies. After the war, he oversaw background checks of workers at a Seattle plutonium plant.

In 1954, eager to move up in the ranks, Felt made an appointment to see Hoover about heading an FBI field office. Six days later, Hoover transferred him back to Washington before sending him to work his way up to management via stops in bureaus in New Orleans, Los Angeles, Salt Lake City and Kansas City. In 1964, Hoover named Felt head of the agency’s inspection division.

By 1971, Hoover had promoted Felt to deputy associate director, asking him to help his longtime second-in-command, Clyde Tolson, who was in declining health. Felt became in effect the second-ranking official in the bureau.

After Hoover’s death, Tolson’s retirement and Gray’s resignation, Felt was in command, but only for a few hours. Nixon named William Ruckelshaus, chief of the Environmental Protection Agency, to head the bureau. Rankled by his new boss, Felt retired on June 22, 1973, after 31 years of service. But he did not fade away.

In 1976, with President Carter promising to punish lawbreakers in government, a grand jury began investigating FBI break-ins unrelated to Watergate. Felt was subpoenaed and almost blew his cover as Deep Throat.

According to Woodward, Felt was asked by Stanley Pottinger, the assistant attorney general heading the civil rights division, whether the Nixon White House had pressed the FBI to conduct “black-bag jobs” -- covert break-ins to gain intelligence data in domestic security cases. While denying there was any pressure, Felt made an off-hand remark, Woodward wrote, that “he was such a frequent visitor of the White House during that time period that some people thought he was Deep Throat.”

After Pottinger and his Justice Department colleagues completed their interrogation, the jurors were asked if they had any questions for Felt. According to Woodward, one juror asked a simple question, “Were you?”

“Was I what?” Felt inquired.

“Were you Deep Throat?”

Felt said no but was visibly shaken, Woodward wrote. Recognizing the delicacy of the situation, Pottinger told the court stenographer to stop taking notes. He approached Felt and quietly reminded him that he was under oath and needed to answer the question truthfully.

Then he gave Felt an out. He told him that he considered the question outside the purview of the investigation and would have the question withdrawn if Felt asked him to do so.

Felt quickly made the request, but in doing so he gave Pottinger the answer to the question.

Pottinger relayed the story to Woodward at a luncheon in 1976 but, apparently believing in the right of reporters to have confidential sources, kept the tale of the grand jury testimony quiet.

Felt and Edward S. Miller, another former FBI official, were indicted on charges of authorizing illegal break-ins in pursuit of members of the Weather Underground, a radical left-wing group that advocated violence in overthrowing the government. On the witness stand, Felt wept as he acknowledged that he had approved 13 secret break-ins by FBI agents between May 1972 and May 1973, roughly the same time he was talking to Woodward about Watergate.

He and Miller were convicted and fined in November 1980 of conspiring to violate the civil rights of relatives of the Weather Underground, whose homes had been burglarized.

President-elect Reagan pardoned them, and their indictments were later overturned.

Nixon, who had testified in Felt’s defense in the case, died in 1994 not knowing that his hunch about Deep Throat’s identity had been correct.

Otherwise, after Felt was cleared of the civil rights charges, the former president likely would not have sent him a bottle of champagne with a personal note that said, “Justice ultimately prevails.”

Felt’s wife died in 1984. A list of survivors was incomplete.

Neuman is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.