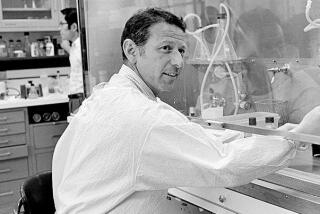

George B. Rathmann dies at 84; co-founder of biotech giant Amgen

- Share via

George B. Rathmann, a far-sighted entrepreneur whose small team of talented scientists created two blockbuster drugs that helped turn his upstart Thousand Oaks firm, Amgen Inc., into the world’s most successful biotech company, died Sundayat his Palo Alto home. He was 84.

The cause was complications from pneumonia, according to his son, Richard.

Biotechnology was still an embryonic business when Amgen opened in 1980. More than a quarter of a century after James Watson and Francis Crick had discovered DNA, the twisting molecular structure that carries life’s genetic blueprint, the elaborate science of isolating key genes in the laboratory continued to elude researchers. Few companies had produced biotech drugs.

Rathmann, a chemist by training and a veteran pharmaceutical executive, was a co-founder of Amgen and served as its chief executive. He helped raise $19 million to fund the firm and assembled a roster of inventive, young scientists who worked in makeshift trailers in then-rural Thousand Oaks.

A big bear of a man with an avuncular personality, Rathmann served as cheerleader for his scientists and as the firm’s chief strategist. He gambled a limited bankroll on a handful of projects, hoping his researchers could discover a lucrative drug before Amgen ran out of money.

One goal was to find the gene for erythropoietin, known as EPO, a hormone thought to trigger the body’s production of red blood cells that carry oxygen. After several false starts, Rathmann threatened to scrap the EPO project. Some staffers worried that it had ruined their careers.

An admitted workaholic, Rathmann arrived at his office one morning before dawn and spotted a light on in the research lab. He walked in to turn the light off, only to discover scientist Fu-Kuen Lin still working on finding the EPO molecule.

Impressed by Lin’s dedication, Rathmann kept the project alive. After two years Lin unlocked the genetic combination to EPO and Amgen later secured a patent. One of Lin’s colleagues likened his discovery to finding something the size of a sugar cube in a lake a mile wide.

In 1989, after several years of tests, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved EPO for sale, and demand was instantaneous. EPO treated chronic anemia in kidney dialysis patients who suffered frequent and painful blood transfusions. It proved to be a remarkable tonic, quickly boosting red blood cell counts and allowing many chronically bedridden patients to resume normal lives. Within weeks of treatment, some patients were fit enough to run in 10K races. “It’s a product for which there is no alternative,” Rathmann said.

The drug was versatile in treating other forms of anemia, including in patients undergoing chemotherapy or radiation for cancer and those with HIV and rheumatoid arthritis. A black market for EPO also developed in sporting circles, and allegations surfaced about cyclists in the Tour de France and Olympic track athletes who secretly used EPO to boost their performance.

As Amgen’s profits soared, the company faced a complex legal challenge. A rival, Genetics Institute, held a separate EPO patent and sued Amgen for patent infringement. Rathmann dismissed the other company’s patent as having “no benefit for society” because its version of EPO couldn’t be mass-produced. He called the lawsuit “blackmail” and refused to settle out of court.

Some members of the close-knit biotech community criticized his strategy. Nobel Laureate Watson said Rathmann “was confusing his anger with good business sense.”

Rathmann was stung by Watson’s comments, but he was vindicated years later when courts ruled in Amgen’s favor.

About 18 months after EPO reached market, the FDA approved a second biotech drug from Rathmann’s pipeline. This drug stimulated production of infection-fighting white blood cells and quickly became a wonder product widely used in cancer chemotherapy.

Both products generated sales of $1 billion a year and triggered Amgen’s dandelion-like growth. Today the biotech firm has 17,000 employees in 40 countries and remains one of the most valuable companies headquartered in Southern California, with a market value of $54 billion. As Amgen’s headquarters grew into a sprawling complex it also served as a magnet, luring other businesses and helping to transform Thousand Oaks into a wealthy enclave.

Unlike many executives who built successful companies, Rathmann let go of the reins early. After handpicking a successor he retired as Amgen’s chairman in July 1990. He correctly forecast that Amgen’s first two products were so valuable they would propel the company into a major drug powerhouse, but that required building a vast corporate bureaucracy and Rathmann preferred science over day-to-day management.

Then in his early 60s and wealthy — Rathmann’s Amgen stock was already worth about $100 million — he planned to serve on the boards of a few start-up biotech firms, play with his grandchildren and go skiing. Soon he was bored.

In late 1991 he took over as chief executive of a small Seattle biotech firm, Icos Corp., hoping to duplicate his Amgen magic. By now, Rathmann was a money magnet. Bill Gates, Microsoft’s co-founder, wrote a check for $5 million after listening to Rathmann’s business plan.

“Basically this is a concept company,” Ned Hamarat, president of Beekman Capital Management Ltd., said of his recommendation to investors regarding Icos. “You’re buying people. More than anything else, George Rathmann was the primary reason” to buy the stock.

Rathmann’s new team of scientists set out to discover biotech drugs that would halt chronic inflammation in debilitating diseases, but there was no breakthrough. Rathmann retired in 2000 from Icos, which later had modest success selling a drug to treat impotence.

Afterward, Rathmann served on the boards of two small biotech firms, still eager to inspire the drumbeat of research.

George Blatz Rathmann was born on Christmas Day 1927 in Milwaukee. He was drawn to science and was inspired by an older brother who was a chemist. Initially, Rathmann planned to attend medical school and sped through his undergraduate work at Northwestern University in three years before changing plans and earning a doctorate in physical chemistry at Princeton. He worked at several companies and rose to director of research at Abbott Laboratories before quitting the pharmaceutical firm to enter the struggling field of biotechnology.

As the decades passed, Amgen’s drugs became so widely used that some relatives of the company’s original group of employees became patients who relied on them. And in his late 70s, Rathmann himself became a dialysis patient and took EPO.

Until the end of his life, Rathmann was a celebrity in medical and financial circles because of his role as chief architect of Amgen’s stunning success. At business forums he happily recalled Amgen’s early days and his quest for scientific discovery. Sometimes those in the audience would tell him how his wonder drugs had saved their lives.

When he heard their stories, Rathmann often wept.

In addition to his son Richard, he is survived by his wife of 61 years, Joy; son James and daughters Margaret, Laura Jean and Sally Kadifa; and 13 grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.