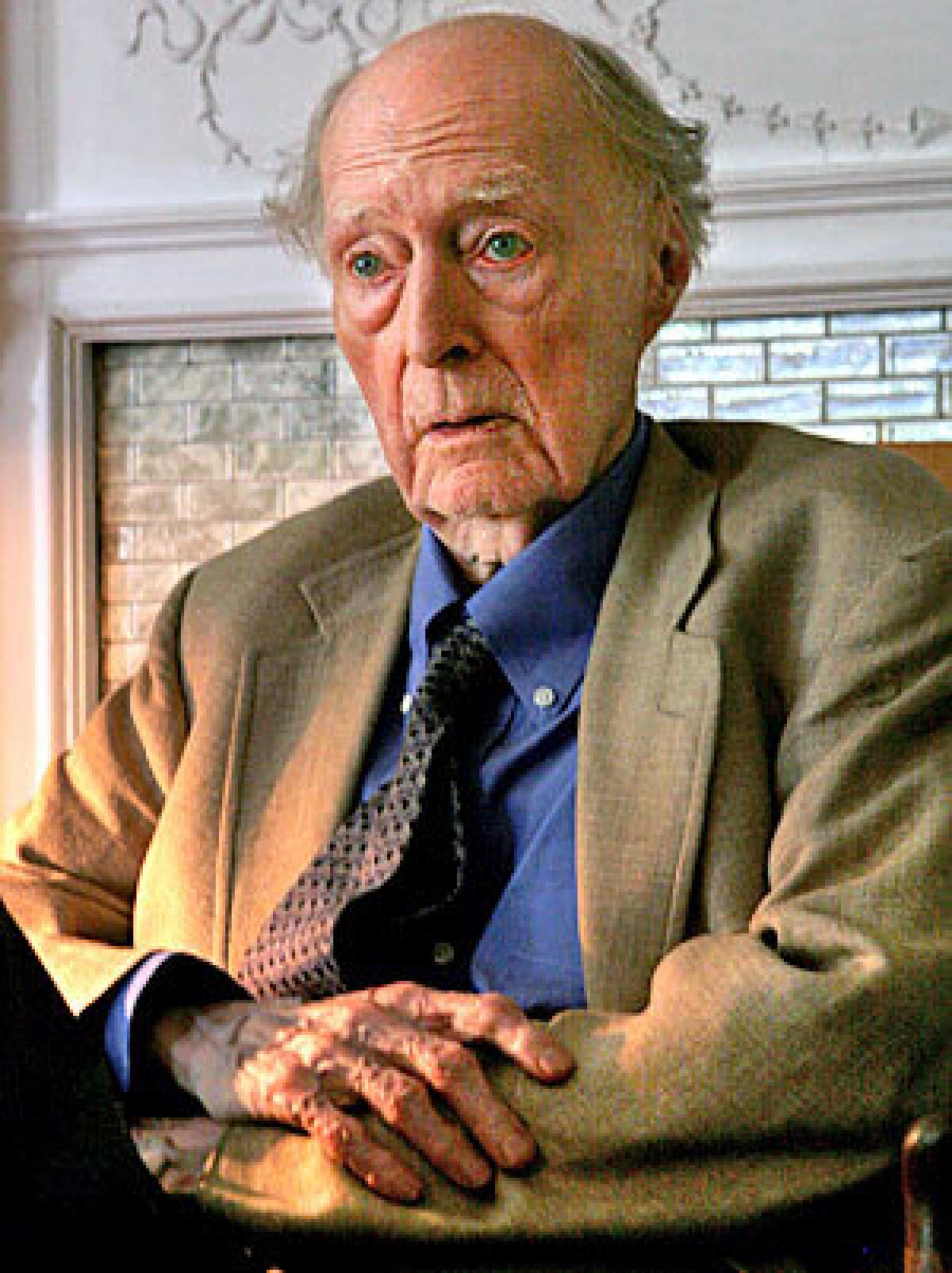

James Purdy dies at 94; writer best known for underground classics

- Share via

James Purdy, a shocking realist and surprising romantic writer who in underground classics including “Cabot Wright Begins” and “Eustace Chisholm and the Works” inspired censorious outrage and lasting admiration, has died. Harold Associates, his literary agent, said he was 94.

Spokesman Walter Vatter of Ivan Dee Publishers said Purdy had been in poor health and died Friday morning at Englewood Hospital in New Jersey.

Purdy published poetry, drawings, the plays “Children Is All” and “Enduring Zeal,” the novels “Mourners Below” and “Narrow Rooms,” and the collection “Moe’s Villa and Other Stories.” Much of his work fell out of print, but several books were reissued in recent years. In the spring, Ivan Dee will issue a collection of his plays.

Gore Vidal, Tennessee Williams and Dorothy Parker were among his fans, but Purdy won few awards and was little known to the general public. He spent most of his later years in a one-room Brooklyn walk-up apartment, bitterly outside what he called “the anesthetic, hypocritical, preppy and stagnant New York literary establishment.”

He was attacked for his “adolescent and distraught mind,” accused of writing “fifth-rate, avant-garde soap opera” and was left out of the country’s official literary establishment -- the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He was also called a comic genius worthy of Voltaire and an outlaw, in the best sense, among his compromised peers.

Interviewed by the Associated Press in 2005, Purdy recalled being “exposed to everything” as a child, and his books revealed the most detailed awareness of sex, violence, race, class, familial cruelty and romantic longing. His work was labeled “gothic” for its extremes of emotion and physicality, but in his own mind there was no sensationalism, just the impulse to write what he knew.

“When you’re writing, at least in my case, you’re so occupied by the story and the characters that you have no interest in what people may think or whether I should write to please anyone,” he said.

Purdy was born in Fremont, Ohio. His parents split up when he was young, forcing Purdy to alternate among the homes of his mother, father and grandmother. He called his formal education essentially a waste, although Sunday school did impart an appreciation of the King James Bible.

He wrote stories from an early age and in his 20s submitted some to what he called “the New York slick magazines,” which duly rejected them. A break came in his early 30s when through a mutual acquaintance he was introduced to Chicago businessman and literary critic Osborn Andreas, who agreed to privately publish a story collection, “Don’t Call Me by My Right Name.”

Others soon learned about him, including British writers Dame Edith Sitwell and Angus Wilson; and his official debut, “63: Dream Palace,” came out in 1956. He followed with such novels as “The Nephew,” “Malcolm” and “Cabot Wright Begins,” stories of innocent young men, needy older women and, in the case of “Cabot Wright,” literary elitism, sexual violence and indiscreet bodily noises.

Rarely were reviewers so divided. Orville Prescott, book critic for the New York Times, labeled “Cabot Wright” the “sick outpouring of a confused, adolescent and distraught mind” and complained of Purdy’s “obsessive concentration on perverted and criminal sexual activities.”

But Susan Sontag, also writing in the Times, likened “Cabot Wright” to Voltaire’s “Candide” and praised it as a “fluid, immensely readable, personal and strong work by a writer from whom everyone who cares about literature has expected, and will continue to expect, a great deal.”

His most influential novel, “Eustace Chisholm and the Works,” was published in 1967 to knee-jerk repulsion and eventual acclaim as a landmark of gay fiction. Set in Depression-era Chicago, “Chisholm” is a 20th century “Satyricon”; but it’s also, through the passion of two men, a quest for “that rare thing: the authentic, naked, unconcealed voice of love.”

Reviewing the book in 1967 for the New York Times, Wilfrid Sheed called “Eustace Chisholm” a “form of charade or peep show” and placed it in “that line of homosexual fiction which announces itself not by subject matter but by tone.” By 2005, the novel was respected enough to receive the Clifton Fadiman Medal for Excellence in Fiction, presented to an ailing Purdy by “The Corrections” novelist Jonathan Franzen.

Information on survivors was not available.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.