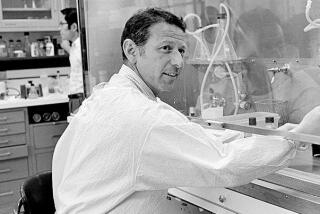

Dr. Richard J. Bing dies at 101

- Share via

Dr. Richard J. Bing, a research cardiologist, composer and author who has been called a “Renaissance man” and “a man for all seasons,” died Monday at his home in La Cañada Flintridge. He had celebrated his 101st birthday a month earlier and had been suffering from heart disease.

One of the last surviving Jewish scientists who fled Nazi Germany to escape persecution, Bing played a major role in the golden age of heart surgery in the 1950s and ‘60s, exploring cardiac metabolism, cardiac catheterization, congenital heart disease and the measurement of blood flow in the heart. He pioneered studies of the role of nitric oxide in the vascular system, work that eventually won the Nobel Prize for three other researchers.

He ultimately published more than 500 research articles. But he also published more than 300 musical scores, including a two-hour “Missa,” and five books of fiction. His musical manuscripts are housed in the Bing collection at the Doheny Library at USC.

“Richard left an indelible mark on cardiology,” Dr. Arnold M. Katz of the University of Connecticut School of Medicine wrote recently. He “was a ‘universal’ man who made enormous and diverse contributions to our understanding of science and art.”

Richard John Bing was born Oct. 12, 1909, in Nuremburg, Germany. He took piano lessons as a child and studied piano in a master class at the conservatory in the Nuremburg Gymnasium, but the major focus of his efforts was composition. He concluded, he later wrote, that a more sustainable career could be achieved in medicine.

To that end, he received his medical degree from the University of Munich in 1934 and a second medical degree from the University of Bern in Switzerland in 1935, joining the Carlsberg Biological Institute in Copenhagen, where he learned to grow cells in test tubes.

There he met Nobel laureate Alexis Carrel of Columbia University and aviation enthusiast Charles Lindbergh, who were visiting as part of their research on attempts to build a pump to keep isolated organs alive outside the body (Lindbergh’s sister-in-law suffered from a heart problem). Because of his facility with Danish, German and English, Bing was assigned to them as a helper.

Impressed, the Americans arranged for Bing to receive a fellowship to Columbia. “I wanted to go to America more than anything,” Bing said in a 2005 interview. “I had no future in Nazi Germany.”

At Columbia, he married Mary Whipple, daughter of Dr. Allen O. Whipple, who developed a procedure for removing a cancerous pancreas commonly called the Whipple operation. She died in 1991 after 52 years of marriage.

When the war broke out, Bing’s lack of a U.S. medical license prevented him from joining the U.S. Army Medical Corps — a problem that was solved by an assistant residency in medicine at Johns Hopkins University. He joined the Army in 1943 and served in the chemical warfare corps in Maryland and then in Germany, rising in rank to lieutenant colonel.

He returned to Hopkins after the war and subsequently held a variety of positions before joining the Huntington Medical Research Institutes in Pasadena in 1969.

At Hopkins, Bing established the third cardiac catheterization laboratory in the United States and the first to study congenital abnormalities. Working with Dr. Helen Taussig, he discovered what is now the well-known Taussig-Bing Malformation, in which, among other problems, the arteries of the heart are transposed.

He used catheters to study metabolism of the heart and found, among other things, that the heart is an omnivore: it can extract energy for its incessant mechanical activity by oxidizing fats, carbohydrates or proteins; that, under most conditions, fats are the desired energy source; and that the heart’s oxygen demand is so great that virtually all the oxygen delivered via the arterial blood is extracted before the blood can leave the heart.

In 1964, working with his wife’s cousin, physicist George Clark of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Bing developed the use of positron-emitting radioisotopes to monitor coronary blood flow in humans, laying the foundation for modern PET imaging.

On the occasion of Bing’s 100th birthday, Microsoft commissioned a short biographical video called “Para Fuera” (roughly translated as “Away With All That,” and named after one of his recent fictional works) to honor him and its Bing search engine. The video, prompted by a tongue-in-cheek letter to the company in which Bing said he had successfully used the name for 100 years, was premiered at Sundance and can be viewed on Youtube.

A daughter, Barbara, died in 1999. Bing is survived by another daughter, Judy Tasker of Thousand Oaks; two sons, John W. Bing of Ewing, N.J., and William W. Bing of Altadena; and numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.