William Shurcliff, 97; Outspoken Physicist on Manhattan Project

- Share via

William A. Shurcliff, a physicist on the Manhattan Project who subsequently became a leading opponent of supersonic transport and President Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative, died June 20 at his home in Cambridge, Mass.

Shurcliff, who spent the latter part of his career designing and promoting solar energy systems, was 97 and died from complications of pneumonia, according to his granddaughter Elizabeth Shurcliff.

Possessor of a strong social conscience spurred -- at least in part -- by his participation in the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan during World War II, Shurcliff turned his strong intellect and will to a variety of causes. They ranged from a 1938 effort to bar German scientists from visits to American laboratories to a recent outburst against the possibility of developing three-dimensional televisions for the home.

He also played a major role in the effort to block development of an American supersonic transport, or SST, arguing that the sonic booms created by the aircraft passing over U.S. airspace would have devastating psychological and financial effects.

Flying at the estimated speed of 1,800 mph, the SST would leave in its wake a 50-mile-wide “bang zone” that would startle unsuspecting residents, shatter windows and lead to the collapse of unstable buildings. Shurcliff argued that a fleet of 150 American SSTs would leave behind $1 million in property damage every day.

In 1967, he organized Citizens League Against the Sonic Boom, which began with only nine members but grew to 1,250 members in 39 states within six months.

About the same time, climate researchers began arguing that emissions from the SSTs would damage the Earth’s ozone layer, allowing increased penetration of harmful ultraviolet radiation.

Swayed by these arguments and others, Congress became convinced that the $3 billion necessary to bring the plane to fruition was an unwise investment, and the project was killed May 20, 1971.

Shurcliff was less successful in his efforts against the Strategic Defense Initiative, Reagan’s 1983 proposal to use ground- and space-based systems to protect the United States against a ballistic missile attack.

Using an approach he had employed in his battle against the SST, Shurcliff wrote all the members of the National Academy of Sciences, seeking their opinions about the practicality of the system commonly known as Star Wars.

Although most did not think the system could work, their opinion had little influence on the administration. Technological difficulties and the collapse of the Soviet Union, however, led to the continual downsizing of the project. It has never been implemented or shown to work.

Shurcliff’s interest in solar energy was spurred by the 1973 oil embargo and, after his retirement as a nuclear physicist, he devoted himself full time to learning about and disseminating information on the uses of solar energy. He wrote several books about the technology, including an early directory of every solar-powered house in the country, and often published them himself, filling mail orders from his living room.

Reading about most solar design work was “infuriating,” he said in a 1980 interview in the New York Times. “Half the information was missing, and systems were vaguely described as ‘ingenious’ without explaining how they were ingenious or how well they worked. Sense had to be made of it.”

His designs received wide acclaim, but he refused to show up to receive awards for them, arguing that the ceremonies featured “too much talk and beer.” After the first few years, he also stopped patenting his designs in an effort to make them more widely available.

William Asahel Shurcliff was born in Boston on March 27, 1909. He learned about activism from his mother, Margaret, who founded a civil liberties group that, among other things, protested the execution of Italian anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti.

He received a doctorate in physics from Harvard University, then joined the American Cyanamid Co., where he helped develop the formula for the official military camouflage paint.

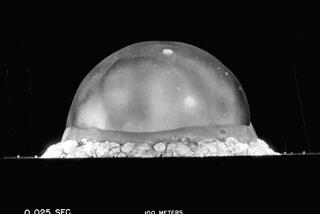

He spent most of World War II working for the U.S. Office of Scientific Research, evaluating proposals and helping to keep Manhattan Project patents from becoming public knowledge. After the war, he was co-editor of the so-called Smyth Report, the official history of the project named for its author, Princeton University physicist Henry DeWolf Smyth.

From 1948 to 1960, he worked for the Polaroid Co., founded by his Harvard classmate Edwin Land. He collected more than 20 patents involving polarized light and other optical technologies. He then moved to Harvard, where he “smashed atoms” at the Cambridge Electron Accelerator until it closed in 1973.

Shurcliff is survived by his wife of 65 years, the former Joan Hopkinson; two sons, Arthur of Cambridge and Charles of Ipswich, Mass.; and two granddaughters.