What does Arnold do now?

- Share via

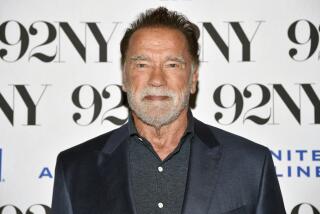

AFTER HIS VICTORY in the 2003 recall election, Arnold Schwarzenegger was often compared to Ronald Reagan, the movie actor turned governor who parlayed his showmanship into the presidency of the United States. But after two disappointing years in Sacramento and the decisive rejection Tuesday of his package of ballot initiatives, Gov. Schwarzenegger’s reign resembles the political career of another celebrity outsider, Jesse Ventura of Minnesota.

All of these celebrities campaigned as populists against career politicians, and they disdained the Legislature. All took office burdened by inherited budget deficits. But Reagan in his first year as governor in 1967 surprised friends and foes alike by agreeing to what was then the largest tax increase ever enacted by any state, and a progressive tax at that. (Its price tag of $1 billion would be more than $5 billion in today’s dollars.)

The tax bill was carried in the Legislature by future Republican Gov. George Deukmejian, then a state senator, but much of it had been crafted by the staff of Jesse Unruh, the powerful speaker of the Assembly. Unruh was doubly pleased. He supported the tax hike on its merits and also believed, as he told me, that it would come back to haunt Reagan when he ran for reelection.

It didn’t turn out that way. The tax increase gave Reagan running room and enabled him to increase education spending, among other things. By 1970, when he ran for reelection, it was barely remembered. Reagan defeated Unruh, the Democratic nominee, by half a million votes.

Fast forward to 1998, when Ventura was elected governor of Minnesota. He too was advised of the necessity for new taxes to erase a deficit and provide more money for schools. Ventura would have none of it. Instead, he insulted legislators. By the time Ventura came around to agreeing that a tax increase was needed, he had become so unpopular he couldn’t get it. Facing likely defeat, he declined to run for reelection in 2002.

Schwarzenegger has followed a similar course. He too has called legislators names and bowed to anti-tax pressures. And he has less excuse than Ventura, who was elected as an independent. Schwarzenegger staffed his administration with aides who had served under fellow Republican Gov. Pete Wilson.

In 1991, Wilson followed the Reagan model and proposed a tax increase to wipe out an inherited deficit. He balanced the tax hikes, which Republicans detested, with cutbacks in social programs, which Democrats disliked. Schwarzenegger retreated on both fronts, restoring budget cuts he had signed off on when John Burton, then the state Senate leader, refused to accept them.

Tax increases are not magic. A case can be made, as Wilson did, that budget restraint was more vital than tax hikes in putting California’s fiscal house in order. An across-the-board tax increase of the magnitude signed into law by Reagan when tax rates were lower would be unlikely to fly today in the Legislature, even with Democrats.

There were, however, other alternatives, among them a modest tax increase on the wealthiest Californians. Acceding to the most intransigent wing of his party, Schwarzenegger rejected this idea. Without increased revenue, Schwarzenegger had to renege on a promise he had made to increase education spending by $3.1 billion. He paid the price when the California Teachers Assn. led a furious and successful attack on his ballot measures.

But Schwarzenegger has time, if he has the will, to rescue himself in the next act. An initiative circulating for next June’s ballot would impose a 1.7% state tax on income exceeding $400,000 a year for single people or $800,000 for couples filing jointly. Its author is actor/director Rob Reiner, who wants to spend the money for universal kindergarten. But a little-noticed provision of the initiative would allow the Legislature to use the money for other purposes, including deficit reduction, until 2010.

Political ideas cannot be copyrighted. Schwarzenegger could preempt the initiative by embracing such a tax increase and urging the Legislature to enact it. This tax, which would produce $2 billion in its first full year of operation, would help him carry out another promise. When he came into office, Schwarzenegger observed that Californians pay more in federal taxes than they receive in federal benefits, and he promised to change this. Nothing has changed. But because taxpayers can deduct state taxes from their federal tax bill, an increase in state taxes for the wealthiest Californians would in effect transfer this money from the federal treasury into the state’s.

Schwarzenegger says he has heard the voice of the voters and wants to work with the Legislature. If he is also willing to reconsider his opposition to any and all tax increases, even at the risk of alienating the hard core in his own party, he may yet prove a Ronald Reagan instead of a Jesse Ventura.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.