Biden gets do-over 20 years later

- Share via

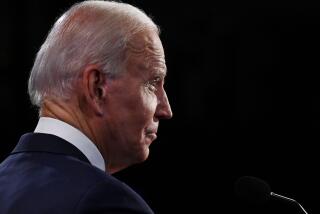

EMMETSBURG, IOWA -- Sen. Joseph R. Biden Jr., in a dark suit whose jacket he will soon shed, steps out of a dark SUV about an hour and a half late for a house party at Jack and Kay Kibbie’s place. Jack Kibbie is a corn and soybean farmer, but more to the point, president of the Iowa state Senate -- and for any Democrat aspiring to the White House, a valuable endorsement.

He would have been here sooner, Biden explains to Kibbie, but there was a little, ah, problem as his plane came in from Des Moines. “You’re not gonna believe this,” Biden says, plainly enjoying the moment. “We got about to the treetops, and the pilot says, ‘Oops. Can’t land here. Too windy.’ ”

So Biden’s plane made a detour, and he arrived to make his pitch for the Democratic presidential nomination a bit later than he’d planned.

About 20 years later than he’d planned, if you want to get metaphorical about it.

Biden’s first presidential campaign ended disastrously in 1987, crumbling amid reports that he lifted some of his best lines from other politicians, plagiarized a paper in law school, picked a fight with a voter in New Hampshire.

Then 44, he’d already been a U.S. senator for 14 years and, as chairman of the judiciary committee, was leading what would be a historically important fight against President Reagan’s Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork. In the crucible that is a presidential run, Biden melted down.

“I didn’t deserve to be president,” he says while flying between Des Moines and Dubuque on a six-day swing through Iowa over the Memorial Day holiday. “I wasn’t mature enough.”

Depth of experience

At each stop, he reminds Iowans that he’s been around long enough to have served with seven presidents through three wars.

As a 30-year member, and now chairman, of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Biden is campaigning as a statesman, and thinks he is the only candidate who has offered a viable solution to the nation’s most pressing problem: Iraq.

“Right now I am absolutely convinced that the American public and Democratic Party are looking for someone with the breadth and depth of knowledge in foreign affairs and national security policy, as well as the ability to empathize with the circumstances of average, middle-class people,” he tells an approving crowd in the Kibbies’ backyard. “If I am wrong about that, then I am not your candidate. And I will die happy without ‘Hail to the Chief’ ever having been played for me.”

He hopes voters see that what he lacks in money and pizazz -- he is vying, after all, in a field that could produce, in New York Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton, the first woman; in Illinois Sen. Barack Obama, the first African American; or in New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson, the first Latino Democratic presidential nominee -- he more than makes up for in experience.

And, Biden says, “I am fully prepared to match my character against anyone running.” He rues the tepid way he believes the party’s 2004 nominee, Sen. John F. Kerry of Massachusetts, responded to Republican attacks.

“They go after me, they got a fight,” Biden says.

This time around, he believes he is scandal-proof.

“To the best of my knowledge, anything that is embarrassing about my past is pretty well public record,” he said. “Any of you who take a look at my life will not be able to conclude that I am not an honorable man.... And that’s why I wasn’t afraid to get back into this thing.”

But Biden’s reputation as someone in love with the sound of his own voice, who muffles his message by sticking his foot in his mouth, has dogged him.

In January, a clumsy compliment paid to Obama backfired, overshadowing his first week as a presidential candidate. In an interview, he said Obama was appealing as a candidate as “the first mainstream African American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy.”

Biden says he’s unfazed by poor press. “There isn’t anybody out there who is a major political figure who hasn’t had somewhere between 20% and 40% of the people out there thinking he’s a jerk.”

Still, he does speak like a man who has been singed, if not burned at the stake, by bad press. He checks himself regularly, with phrases such as “I don’t know for a fact” and “correct me if I misstate this.”

‘Ideas trump money’

Biden is at home in a crowd, appearing at ease, squeezing people’s shoulders as he talks and kissing women’s hands. He sometimes gets tangled up in a story or interrupts a compelling point with a distracting aphorism (“As my mom used to say ... “), but he connects.

“He’s bright, warm and experienced,” said Ann Heinz, 54, a sales rep for a textbook company who hosted Biden in her bunting-draped Dubuque backyard.

“He was very impressive,” said Cathy Hladky, at a house party in Indianola. “We’ve got to finish the war.”

“He has got the highest conversion rate of any candidate I have ever seen,” said Bill Romjue, Biden’s Iowa campaign director, referring to the number of neutral or undecided voters who sign up as supporters after seeing the candidate in person.

Despite raising relatively little money ($4 million in the first three months of the year, and a hint that his six-month total will be closer to $15 million, compared with Clinton’s $36 million in the first three months) and polling numbers in the low single digits, he is upbeat.

“Ideas trump money,” he likes to say, especially in Iowa, where voters like to say they don’t feel they know a candidate until they’ve shaken his or her hand at least twice.

At each house party, Biden talks easily about his family, and often introduces Jill, his wife of 30 years, and their 26-year-old daughter, Ashley.

Jill, 56, teaches English at a community college and received her doctorate in education in January. A petite blond, she runs 5 miles five times a week, and lifts weights to keep osteoporosis at bay. On a steamy Des Moines morning, she runs along a riverbank, wearing a running bra and bike shorts, and laughs in embarrassment when a reporter crosses her path.

“I didn’t think I was going to run into anyone who knew me out here,” she says.

Biden’s elder son, Beau, 38, is Delaware’s attorney general and a captain in the Army National Guard. His younger son, Hunter, 37, is a Washington attorney.

But his most compelling family story never comes up on the trail. In 1972, a week before Christmas, and just after he’d been elected to the U.S. Senate for the first time at age 29, his wife, Neilia, and his baby daughter, Amy, were killed in a car crash. Beau and Hunter, then 4 and 3, were seriously injured.

Biden, who was not with them, initially planned to give up the seat but was talked out of it. He was sworn in at his sons’ side, in the hospital’s pediatric wing.

In 1988, on the eve of the New Hampshire primary, Biden had his own brush with death. Suffering blinding headaches, he was rushed to a hospital, where doctors discovered two brain aneurysms, balloon-like weak spots in the blood vessel walls. One of them burst while he was on the operating table.

Today he is jovial about the surgery: “I have two titanium clips in my head,” he says during a 20-minute van ride between the Des Moines airport and a house party in Indianola. “I can’t get MRIs now. The magnets would pull the clips out.” His family jokes that doctors “cut the temper cord,” because he is so much mellower.

Biden takes great pleasure in letting people know that in the “millionaire’s club” of the Senate, he is the poor relation. Having spent most of his adult life in public service, his net worth was recently estimated by the Washington Post to be between $100,000 and $150,000.

In 2005, he received a reported $112,000 advance from Random House for a book, “Promises to Keep: On Life and Politics,” that is to be released July 31. (The book, he says, was conceived when he expected to become Kerry’s secretary of State.)

When he talks about education, about how he thinks that teachers should be paid on par with engineers or about his plan to ease tuition burdens on taxpayers earning less than $125,000 a year, he sometimes mentions that he and Jill sold their house in order to help pay for their sons’ tuitions and took a second mortgage to pay for their daughter’s.

No. 1 issue: Iraq

Over the next seven months, Biden’s job is to convince Iowa Democrats that he is their best shot at restoring America’s reputation and to convince everyone else that his candidacy is viable.

If he can shine in the Iowa caucuses on Jan. 14 -- and keep Richardson at bay while Clinton, Obama and former Sen. John Edwards tear one another up -- his dark-horse candidacy could seem less of a longshot. In poll after poll of Democrats, the war in Iraq is named as the No. 1 issue facing the country, and he is hoping this will be seen as his strong point.

Biden was an enthusiastic supporter of ousting Saddam Hussein, but now he -- like the entire field of Democratic contenders -- is an outspoken opponent of the Iraq war. As the fourth or fifth candidate in what is usually cast as a three-person race, he is not often put on the spot about his original vote authorizing President Bush to use force.

In the Victorian home of retired pharmacist Bob Osterhaus and his wife, Ann, in tiny Maquoketa on the eastern edge of Iowa, Biden is laying out his Iraq plan for a Memorial Day crowd of about 40 people.

It is preceded, as is his wont, with a lesson: “Whenever there has been a self-sustaining cycle of sectarian violence, like the one in Iraq, there is only one of four ways it has ever ended,” he says, and three of the four are untenable.

“One: A foreign power comes in and occupies for a generation or two.... We are not the Ottoman Empire or the British Empire, folks; that’s just not in our DNA. Second option: You install a dictator, and wouldn’t that be the ultimate irony?

“The third option is you pick a side, and you help that side wipe out the other side. That is not an option for us and would likely ignite a Sunni-Shia war from the Mediterranean to the Himalayas.”

The fourth and only workable solution, he believes, is to federalize Iraq by creating three autonomous regions (Shiite, Sunni and Kurd) with a strong central government in Baghdad. A major effort would be made to enlist the support of Iraq’s neighbors, the United Nations and major powers. The U.S. would withdraw most troops by 2008, with a small force left behind to train Iraqis and deal with terrorists. (The plan is posted at planforiraq.com.)

Biden zeroes in on Meredith Brandt, a teacher wearing a photo of her Marine son on her sweatshirt, which says “I left a piece of my heart in Iraq.”

“We have pledged our sacred honor that we will provide for those we have sent to war,” Biden says, “and we care for those who come home from the war.”

As Biden gently squeezes Brandt’s shoulder, her eyes well up.

Here, as at each stop, he says he voted, finally, for the Iraq funding bill because he was able to include funds for armored vehicles with V-shaped hulls, designed to deflect the blasts from the roadside bombs responsible for killing and maiming so many Americans.

He was thinking his vote would get him in trouble now that Americans in general, and Democrats in particular, have soured on the war. “Some issues are worth losing elections over,” he says, anticipating a challenge. Except none comes.

Instead, he hears versions of what Brandt says next: “I would like to thank you for referring to our troops as treasures” -- her son Michael was deployed a month ago -- “because my 23-year-old son is my treasure.”

She continues: “My one big wish for all of them is that they come home with dignity and honor and don’t have to fight for their benefits.”

“I promise you, it will be over my dead body,” Biden says. “I mean it.”

robin.abcarian@latimes.com

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.