Stem cell trial approved for spinal cord injuries

- Share via

Ushering in a new era in medicine, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration said Friday that it had cleared the way for the world’s first clinical trial of a therapy derived from human embryonic stem cells.

By early summer, a handful of patients with severe spinal cord injuries will be eligible for injections of specialized nerve cells designed to enable electrical signals to travel between the brain and the rest of the body. When the cells were administered to rats that had lost control of their hind legs, they regained the ability to walk and run, albeit with a limp.

As a Phase I trial, the study will primarily assess the safety of the treatment, which has been under development by Menlo Park, Calif.-based Geron Corp. for nearly a decade. But scientists, doctors and patients said they were most eager to see whether low doses of the cells would produce any therapeutic benefit.

If so, it would help validate years of hope and investment in the nascent field of regenerative medicine. Besides patients with spinal cord injuries, stem cell therapies could ultimately benefit people with such intractable diseases as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and multiple sclerosis.

The cell therapy is made from one of the first batches of human embryonic stem cells ever created. Researchers had feared those cells could never be used to treat people because they were derived using molecules from mice and cows and thus might be rejected by the human immune system. Newer stem cell lines that are animal-free have not been eligible for federal research funding under the policy set by President Bush in 2001. As a result, many people had expected FDA approval for any embryonic stem cell therapy to be years away.

Now, however, the FDA appears satisfied that the stem cells are safe for human use, and more clinical trials are sure to follow, said Amy Comstock Rick, president of the Coalition for the Advancement of Medical Research, a patient advocacy group that supports stem cell research. “It shows that things are starting to move through the pipeline,” she said.

Dr. Thomas Okarma, Geron’s chief executive, said the timing of the FDA’s decision -- made late Wednesday but announced Friday by the company -- had nothing to do with the change of administrations in Washington. Unlike Bush, President Obama has voiced strong support for human embryonic stem cell research.

“We have no evidence that there was any political shadow over this process,” Okarma said in a conference call with reporters and corporate analysts. Geron submitted its application to test the nerve cells, dubbed GRNOPC1, in April, and the FDA spent an appropriate amount of time evaluating the cells’ safety, he said.

Unlike human stem cells derived from blood or fat, embryonic stem cells are coveted because they are theoretically able to grow into any kind of cell in the body. Scientists are also trying to turn them into insulin-secreting islet cells for patients with Type 1 diabetes and cardiac tissue that could repair damage from heart attacks.

Even if the spinal cord therapy doesn’t make paralyzed patients walk again, it could still substantially improve their quality of life, said UC Irvine neuroscientist Hans Keirstead, whose research team figured out how to convert human embryonic stem cells into the replacement nerve cells.

“I would absolutely love to see a quadriplegic regain use of their thumb,” Keirstead said. “That means that person can get out of bed in the morning and operate their own wheelchair. They can type; they can make phone calls.”

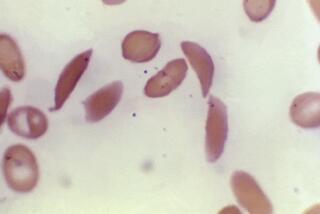

To treat spinal cord injuries, scientists first realized that the crucial damage was to oligodendrocytes, cells that insulate nerve fibers with myelin so that signals can be transmitted to and from the brain. The hard part, Keirstead said, was figuring out the complex recipe of growth factors and other chemicals that would turn stem cells into oligodendrocyte progenitor cells that could ultimately make new myelin.

To test the cells, Keirstead’s team gave rats anesthesia and damaged their spinal cords just enough so they could not walk normally. After seven days, they injected the rats at the site of the injury with the progenitor cells. After four weeks, the rats could walk, run and stand on their hind legs, and their coordination had fully recovered, Keirstead said. The research was published in the Journal of Neuroscience.

UC Irvine researchers spent two years studying hundreds of rats to make sure the injections were safe. Pure embryonic stem cells tend to grow into tumors, but the rats showed no such signs for a year after treatment. Blood and urine tests turned up none of the chemicals that would signal a toxic reaction, said Keirstead, whose work was funded by Geron.

The first patients to get the treatment will be injected with 2 million of the cells seven to 14 days after a spinal cord injury. If they are administered sooner, the cells could be damaged by inflammation from the injury. If doctors wait too long, there might be too much scar tissue for the cells to find room to grow, Okarma said.

Patients will be given a low-dose anti-rejection drug for 60 days to ensure their bodies don’t reject the GRNOPC1 cells, even though research indicates that the cells won’t be recognized by the human immune system, he said. The sites of the clinical trial will be announced in coming months.

Despite the risks, recruiting patients should not be difficult, said Peter Kiernan, chairman of the Reeve Foundation, which funds research to find cures for spinal cord injuries. Some patients already travel overseas for expensive, unproven therapies that purport to use various kinds of stem cells.

Though he hailed the FDA’s decision to allow Geron to proceed with the first phase of its trial, Kiernan cautioned that a cure could still be years away. He said he worried that if the improvement wasn’t immediate and dramatic, people might turn their backs on human embryonic stem cells altogether.

“It’s your worst nightmare,” he said. “There may be some people who say, ‘See, we told you so. It’s all hype.’ ”

--