One year in, Trump’s environmental agenda is already taking a measurable toll

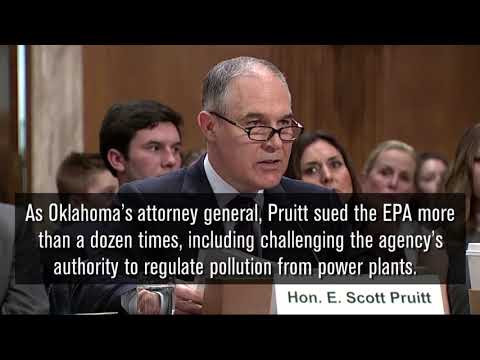

As Oklahoma’s attorney general, Scott Pruitt sued the EPA more than a dozen times, including challenging the agency’s authority to regulate pollution from power plants. He now leads the EPA.

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — A massive coal ash spill near Knoxville, Tenn., in 2008 forever changed life for Janie Clark’s family and left her husband with crippling health problems. So Clark was astounded late last year when she heard what the Environmental Protection Agency had done.

In September, at the behest of power companies, the agency shelved a requirement that coal plants remove some of the most toxic chemicals from their wastewater. The infamous Kingston power plant that released millions of cubic yards of toxic coal ash into area rivers was among some 50 plants given a reprieve.

After the EPA’s action, the plant’s owners delayed new wastewater treatment technology for at least two years.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Clark said. “It is like a slap in the face. It is like everything that has happened is just being ignored.”

One year into the Trump administration’s unrelenting push to dilute and disable clean air and water policies, the impact is being felt in communities across the country. Power plants have been given expanded license to pollute, the dirtiest trucks are being allowed to remain on the roads and punishment of the biggest environmental scofflaws is on the decline.

The real-time impact of the most industry-friendly regulatory regime in decades is at times overshadowed by policy battles that are years from resolution. President Trump’s moves to shrink national monuments, return drilling to the waters off the West Coast and allow natural gas companies to release more methane into the air are destined to be tied up in court for the foreseeable future. The contentious Keystone XL pipeline may never get built as volatile oil prices threaten its profitability.

Yet under EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt, the air and the water are already being affected as the administration tinkers with programs obscure to most Americans, with names like “Effluent Limitations Guidelines and Standards for Steam Electric Power Plants” and “Air Quality Designations for Ozone.”

Pruitt sued the EPA more than a dozen times when he was Oklahoma attorney general, challenging the agency’s restrictions on the fossil fuel industry and authority to protect the nation’s air and water. Now under his leadership, the agency’s enforcement actions against scofflaws have plummeted, agency data indicate.

The numbers emerging from the federal government’s database of enforcement actions against polluters show that from the time Pruitt took the helm early last year through November, the dollar amount of pollution-control equipment and cleanup activity the EPA demanded dropped by more than 85%. Even compared with the dollar amount required during the same period of the George W. Bush administration, there is a dropoff of more than 50%.

“It is one thing to say we have a change of administration and a different level of emphasis and focus,” said Cynthia Giles, who led the EPA’s enforcement office during the Obama administration and has analyzed the recent data. “But this kind of drop is not a change of emphasis. That is abandonment. That is a very, very big deal.”

The EPA strenuously objects to the characterization. The agency says holding polluters accountable remains a priority, that a nine-month snapshot of the data does not tell a complete story and that in many cases the EPA has shifted enforcement of environmental violations to state agencies.

Yet those state agencies often lack the resources and sophistication to handle them.

Even in California, where state leaders defiantly assert that their agencies will hold polluters accountable where the EPA retreats, a case involving large amounts of toxic material at the former Exxon Mobil refinery in Torrance highlights how ill-equipped the state can be for enforcement responsibilities.

When EPA inspectors arrived at the refinery in December 2016, they found 265 tons of toxic material had sat illegally at the site, in unsuitable tanks, for 26 years, according to a copy of their report provided to The Times by the Washington-based Environmental Integrity Project. Such material is supposed to be moved to a hazardous waste facility within a year, according to Kandice Bellamy, a retired EPA inspector in California who was part of the team.

State inspectors had earlier been to the site while the many tons of toxic material sat there, Bellamy said, but apparently had not done anything about it.

State officials refused to comment, saying the refinery remained subject to investigation.

“One of the alarming things with this facility is that not too far in the past there had been an explosion there, and they had to evacuate a sizable chunk of the area,” Bellamy said, referring to an incident in 2015 which the U.S. Chemical Safety Board, which investigates accidents at plants, called a “serious near miss” that could have resulted in a “potentially catastrophic release” into surrounding communities.

“And we still found things that were of concern.”

Bellamy said the federal team was dismayed EPA higher-ups did not pursue the long list of potential violations they drew up, many of them serious. Instead, the case was turned back over to the state.

“We had the sense that they [EPA] had decided not to take on any of these challenging type cases because any refinery operator and their attorney could just appeal directly to the administrator in Washington,” Bellamy said. “And their pleas would most likely be seen favorably by this administration.”

An EPA spokeswoman in Southern California declined to discuss the case, writing in an email that “EPA’s policy is not to comment on investigations nor potential investigations.”

In another case, in southwestern Michigan, the Trump administration abandoned a years-long push to require a coal-fired electrical plant operated by DTE Energy to update its pollution controls.

A federal appeals court had twice upheld the EPA’s position. But the administration changed direction and put the company in the clear. That decision relaxed restrictions on harmful emissions that owners of other coal-fired power plants will be subject to when they expand facilities.

Pruitt announced the new policy in a December memo, writing that it is not the EPA’s place to investigate whether plant operators are lowballing the emissions that renovated facilities will generate.

The move is expected to slow the pace at which plants install state of the art pollution controls, just as the EPA decision that so upset Janie Clark in Knoxville is moving utilities to slow down plans to remove some of the most toxic materials from coal plant wastewater.

The EPA delay of the wastewater rule, made after power companies protested it would cost jobs and undermine Trump’s energy agenda, is having ripple effects across the country.

Coal plants that were poised to start installing the new technology as soon as this year are now balking.

“We were working with a good number of utilities who immediately said we are putting this on hold,” said Jamie Peterson, CEO of San Diego-based Frontier Water Systems, a company that installs the treatment technology.

“If this rule had not been changed, there would be a significant amount of work being done right now,” said Peterson. “The market has dropped by 80 or 90%.” Regulatory documents obtained by the Southern Environmental Law Center confirm that plants are changing their plans.

As the market for high-tech equipment meant to keep some of the most harmful toxins from migrating into drinking water craters during the Trump administration, the market for the highest-polluting trucks is looking up.

The attorneys general of California and 11 other states call the trucks a “pollution menace” that produce 20 to 40 times the harmful emissions of new trucks their size, but the industry that makes “gliders” — trucks built using a new chassis and an old, refurbished diesel engine — has been given a big gift by the administration.

Federal officials are racing to block a rule taking effect this month that aims to keep gliders off the road. The regulation limits the number of new gliders not meeting emission standards to roughly 1,500 each year, nationwide, and eventually bans them altogether. The EPA is moving to change the rule to allow unlimited gliders.

Pruitt pilloried the cap as an attempt by the Obama administration to “bend the rule of law and expand the reach of the federal government in a way that threatened to put an entire industry of specialized truck manufacturers out of business.”

The California Air Resources Board warns the about-face threatens to completely offset all the clean-air gains it has made through the state’s aggressive regulation of heavy diesel trucks and “have a profoundly harmful impact on public health.”

The trucks would continue to roll onto the roads at the same time California and many other states are scrambling to deal with another blow the EPA delivered to their efforts to clean the air. The agency has delayed for at least six months its deadline for declaring which parts of the country are plagued with smog levels that violate new, stricter limits guided by the Clean Air Act.

The EPA’s delay inhibits state and regional air regulators from taking actions to confront the pollution. In California alone, the ozone standards are projected to save as many as 218 lives and prevent 120,000 missed days of school each year.

The EPA says it will have new rules ready by April, but Janet McCabe, who headed the agency’s clean air efforts during the Obama administration, said even so, the delay has consequences.

“If you are an asthmatic exposed to high levels of air pollution, it can mean a lot of missed school days in that six months,” McCabe said.

Follow me: @evanhalper

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.