House approves California drought bill that faces Obama veto

- Share via

The U.S. House on Tuesday passed a California drought bill, despite a veto threat from the Obama administration and its expected demise in the Senate in the final days before Congress adjourns.

The 230-182 vote was largely a symbolic gesture in the years-long effort by House Republicans to weaken endangered species protections that have restricted water deliveries from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta to San Joaquin Valley agribusiness and urban Southern California.

The measure, which was introduced last week after House GOP negotiations with Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) fell apart, was opposed by environmentalists, the White House and Gov. Jerry Brown’s administration.

“This is no time to re-ignite water wars, move water policy back into the courts, and try to pit one part of the state against another,” California Natural Resources Secretary John Laird wrote in a letter Tuesday to the California congressional delegation.

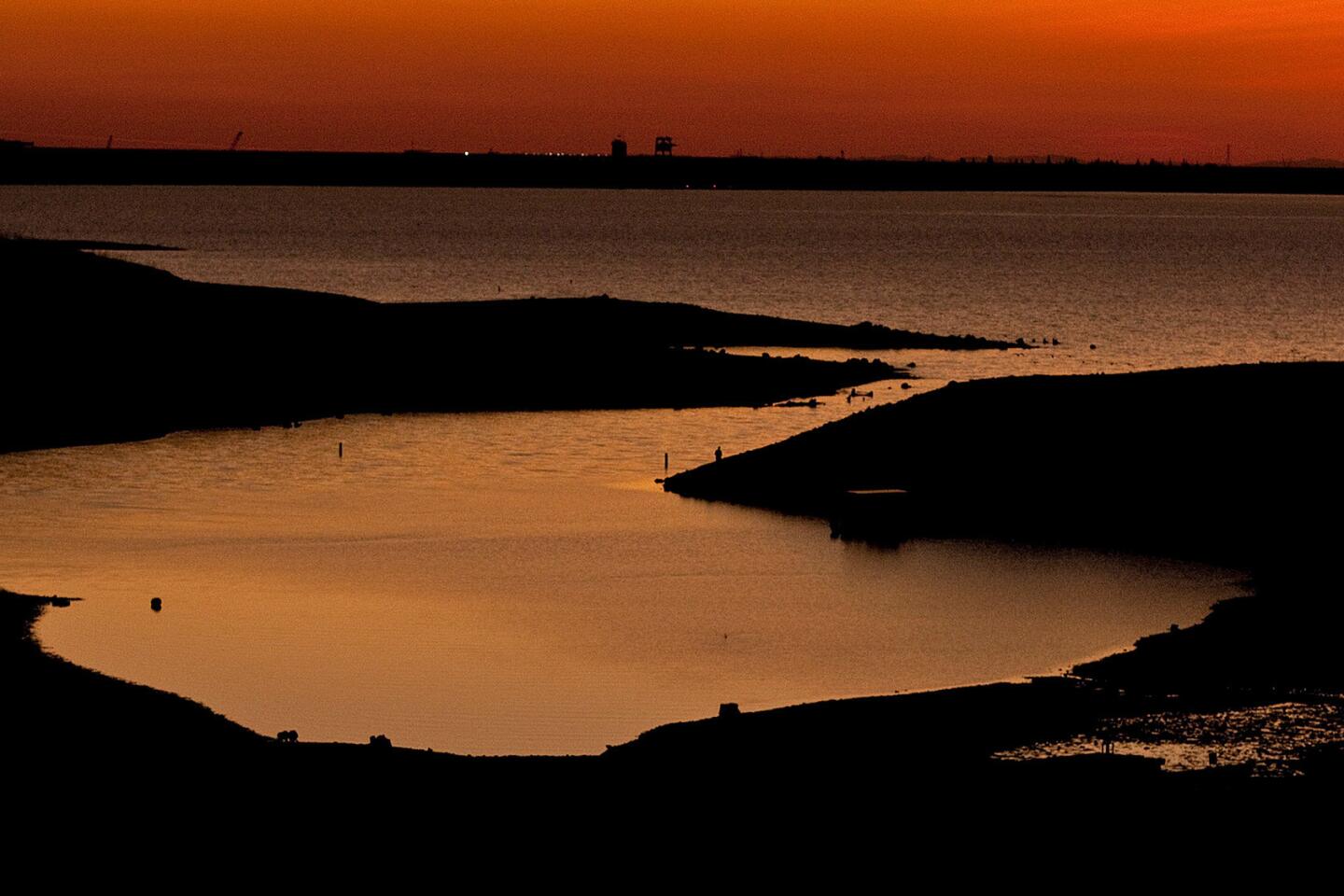

The 26-page bill focused on water operations in the delta and Northern California, directing federal agencies to take steps that would send more delta water south. Proponents of the measure said that endangered fish restrictions had significantly reduced delta pumping during storms in late 2012 and early 2013.

“We have seen farmers who normally help feed the nation being sent to wait in line at food banks and, in some cases … being served carrots imported from China,” said House Natural Resources Committee Chairman Doc Hastings (R-Wash.), during floor debate. He railed against the regulations that he said “have diverted water supplies in order to help a 3-inch fish.”

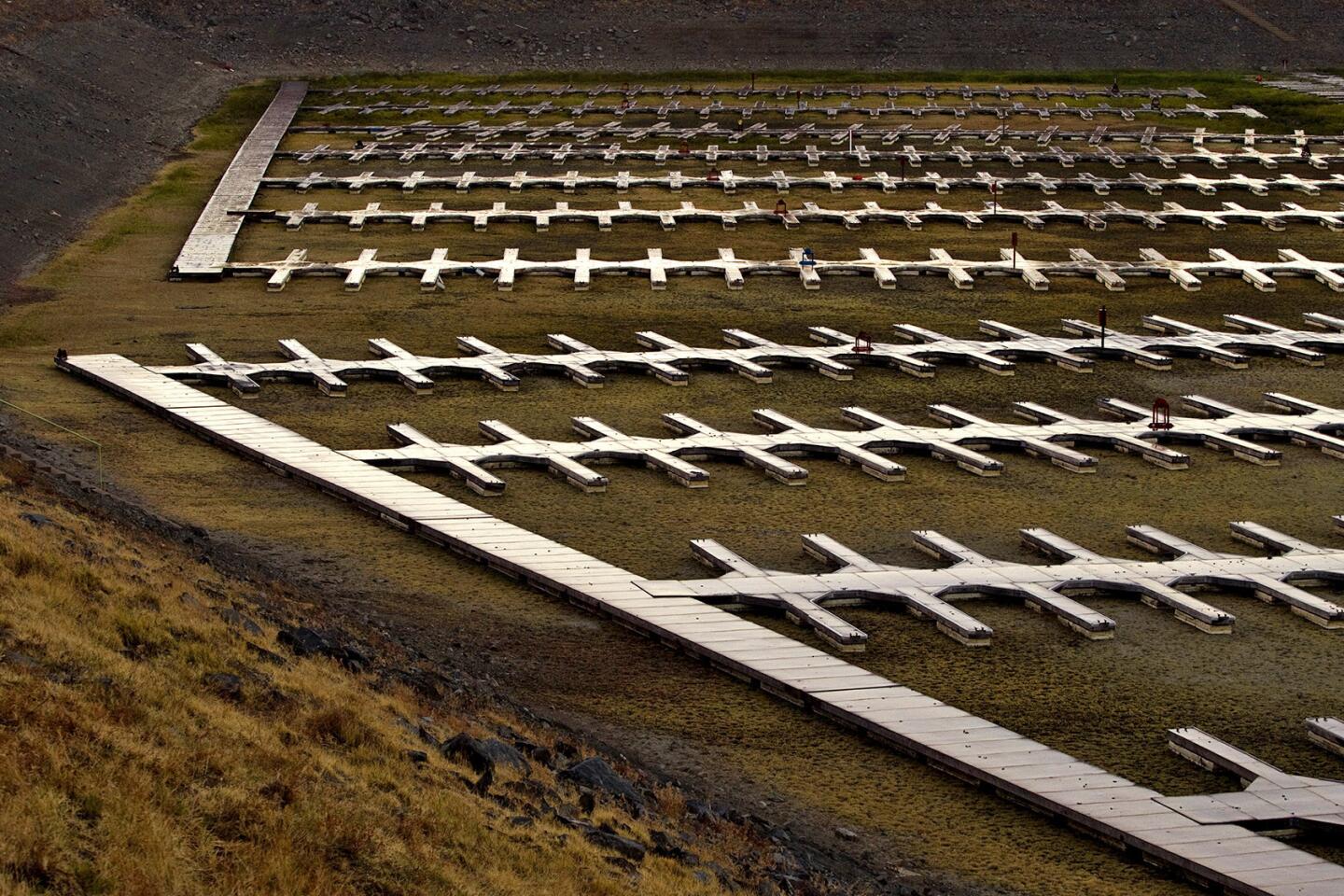

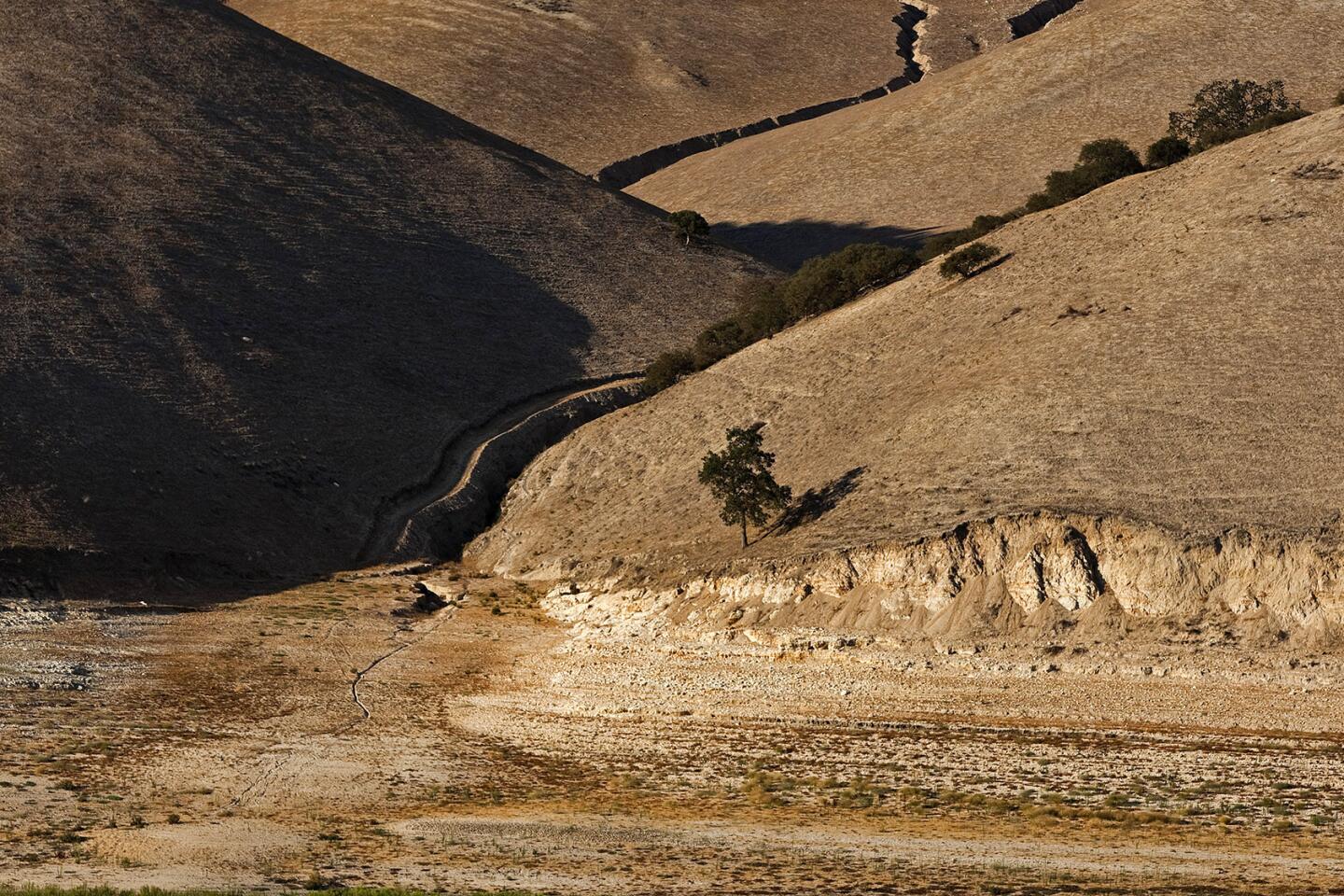

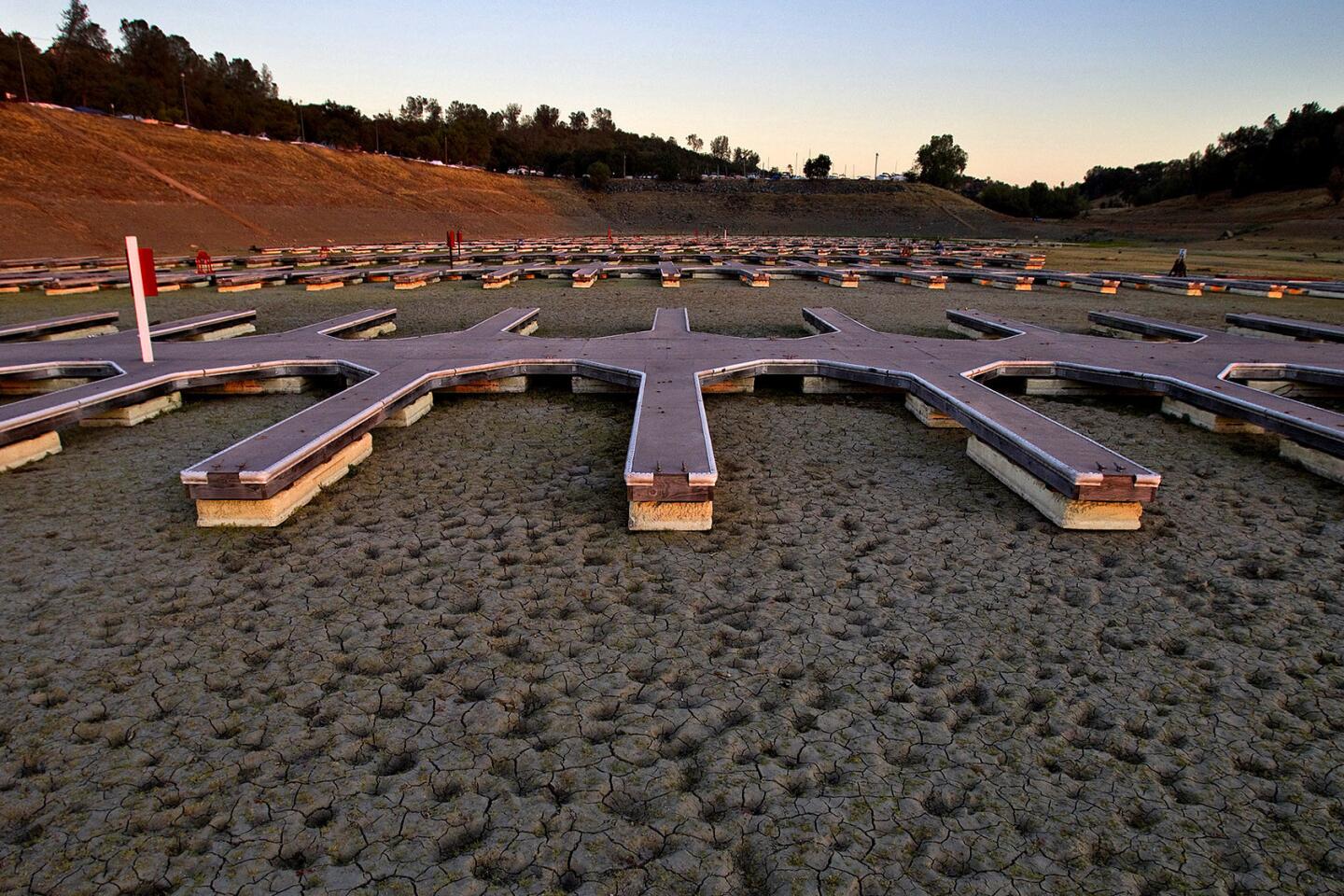

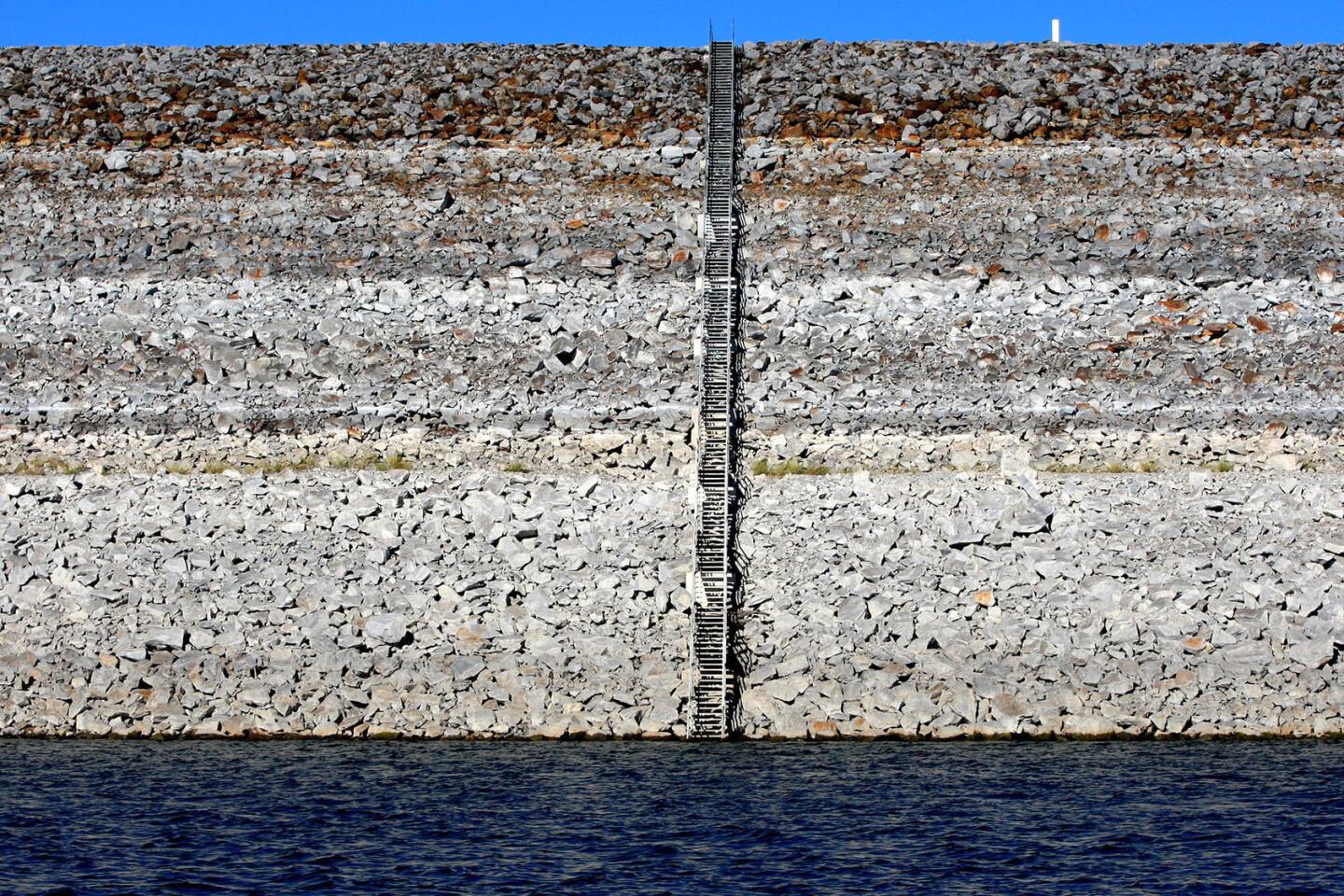

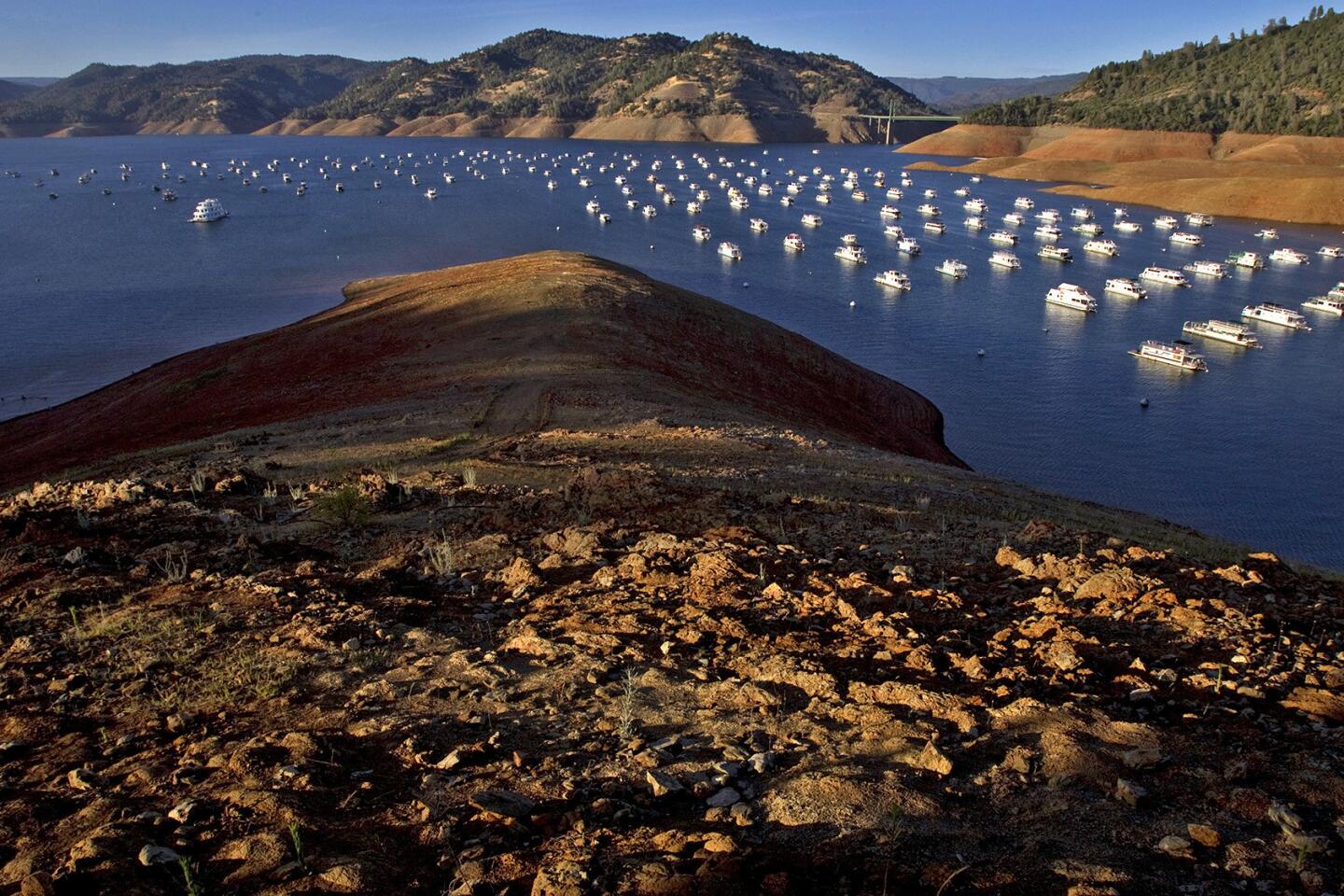

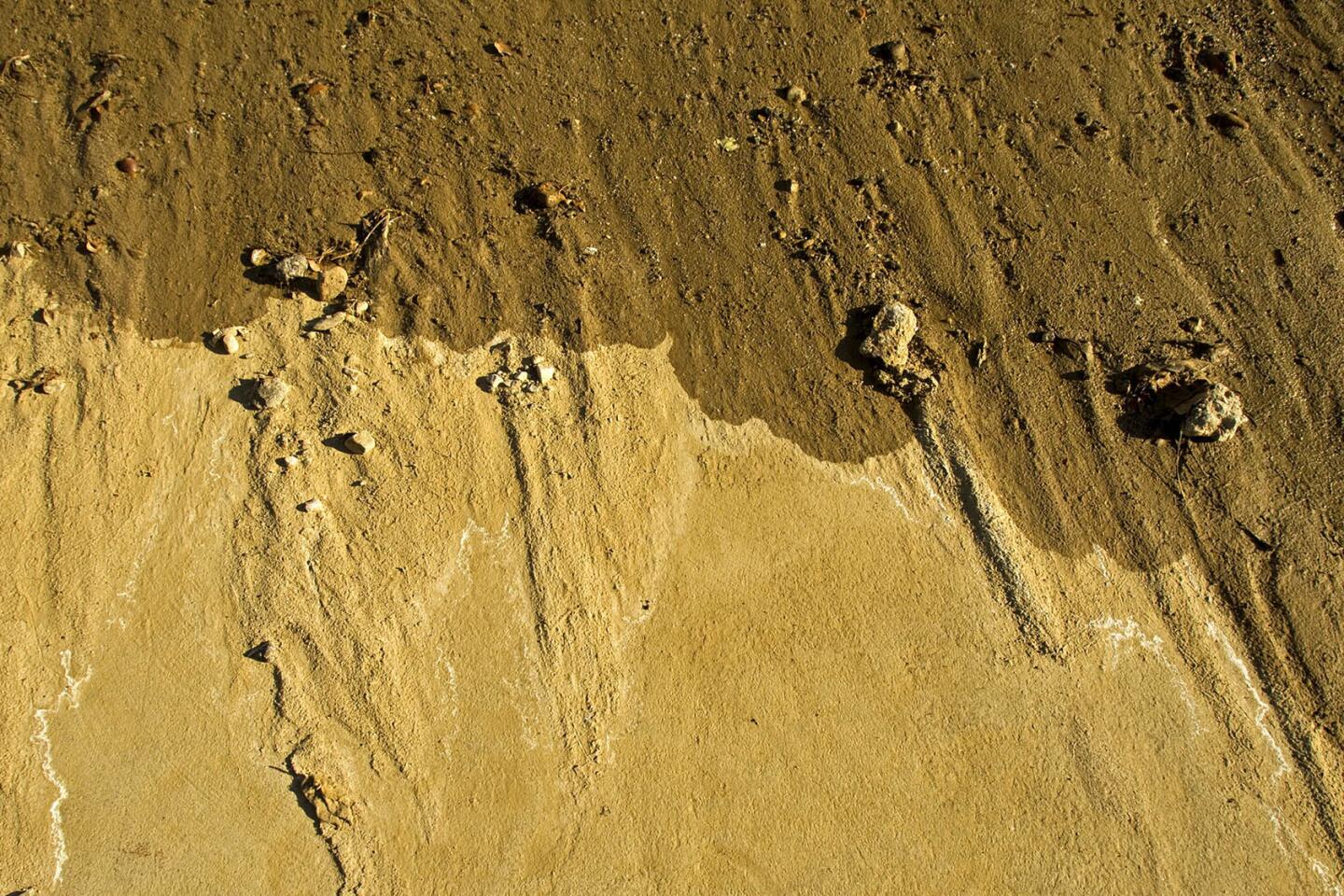

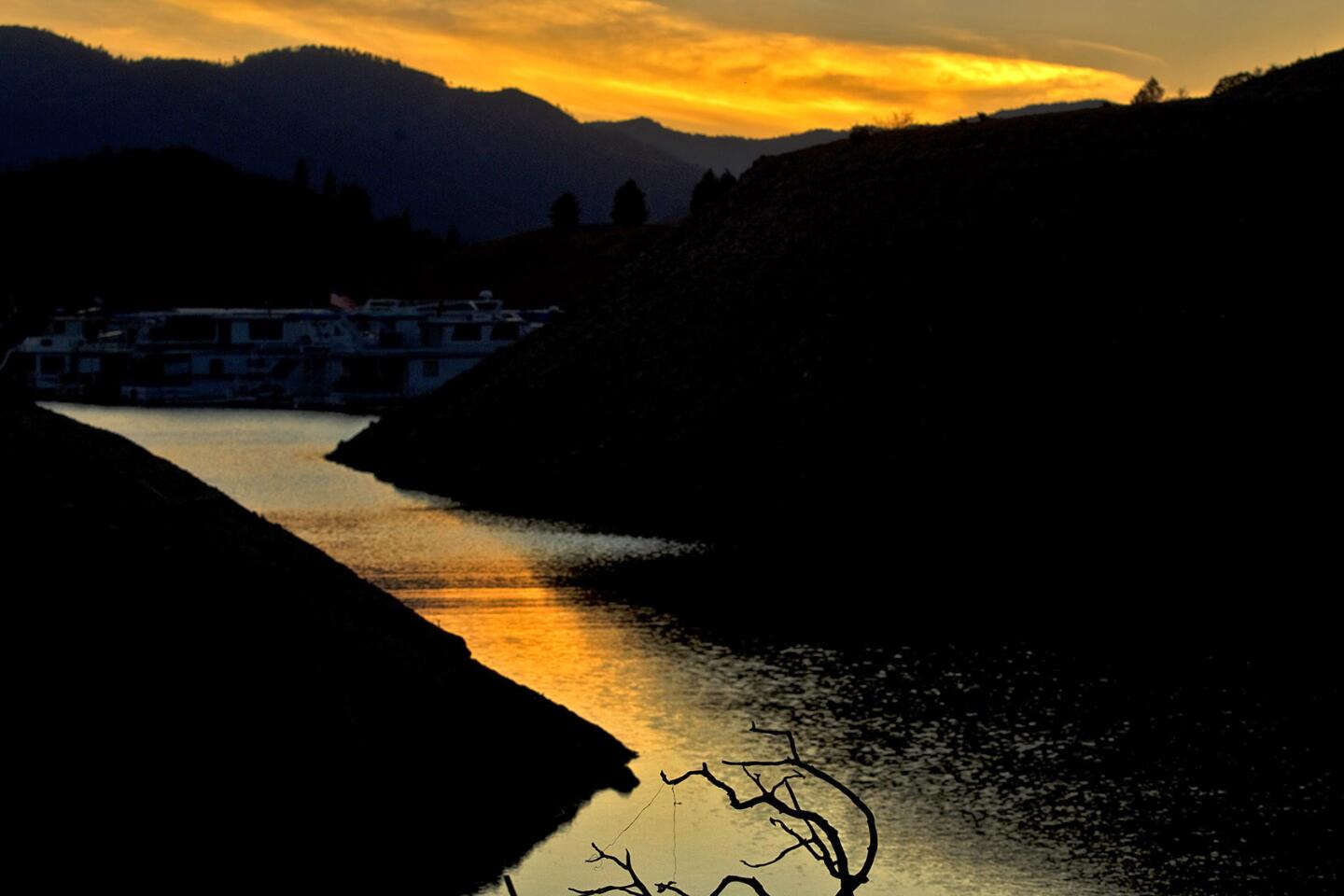

But the House measure would have done little to boost delta deliveries during this third year of the state’s drought, when shrinking reservoirs and scant rain and snow reduced state and federal water allocations to a trickle.

“Last [winter] I don’t recall that we actually lost any water due to restrictions,” said Jeffrey Kightlinger, general manager of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, which like other customers of the State Water Project, got only 5% of requested deliveries this year.

Metropolitan did not take a formal position on the House bill because it lacked bipartisan support. But Kightlinger said the district favored many of the measure’s provisions.

“I think folks are saying, if the governor has declared a drought emergency, then we would expect the agencies to take that into consideration and operate more aggressively,” Kightlinger said.

The bill, he said, was a congressional prod for more flexible water operations, not a dismantling of protections for imperiled salmon and delta smelt.

Environmentalists said that Republicans and water contractors such as Metropolitan and the Westlands Water District were using the drought as an excuse to weaken environmental regulations that have long frustrated them.

“This bill very clearly tries to override the requirements of the Endangered Species Act,” said attorney Doug Obegi of the Natural Resources Defense Council. “It’s obviously a warmup for next year with Senate control by the Republicans.”

The drought debate demonstrated the growing clout of California Republicans. The measure’s key champion was House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy of Bakersfield, who rose to the post only months ago. A longtime ally of agribusiness, McCarthy used his control over the legislative calendar to bring the GOP bill to the floor in the waning days of the legislative session, even though negotiations over a bipartisan bill had collapsed weeks earlier.

As Democrats tried to explain the nuances of water rights, wildlife habitats and the salmon industry, Republicans offered a simpler narrative. Farms are parched, farmworkers are unemployed and the water that could fix things, they argue, is flowing to the ocean.

Devin Nunes, a Central Valley Republican, compared the Democrats who opposed the water legislation to communist bureaucrats.

“This is about San Francisco and Los Angeles getting all of their water, never giving up one drop, and they have taken the water from our communities,” Nunes said. (In fact, delta deliveries have been cut to Los Angeles and the rest of the Southland.)

In the end, though, the Republicans are unlikely this year to overcome formidable opposition from most every major environmental group and Northern California Democrats, some of whom have been fighting the water battle for decades.

That coalition torpedoed Feinstein’s closed-door negotiations with the GOP to draft a compromise bill. And California’s other senator, Democrat Barbara Boxer, last week declared her opposition to the House measure, saying it would undermine federal and state protections and jeopardize the state’s salmon industry.

“It doesn’t look as if it’s going anywhere,” Kightlinger said.

Boxall reported from Los Angeles and Halper from Washington