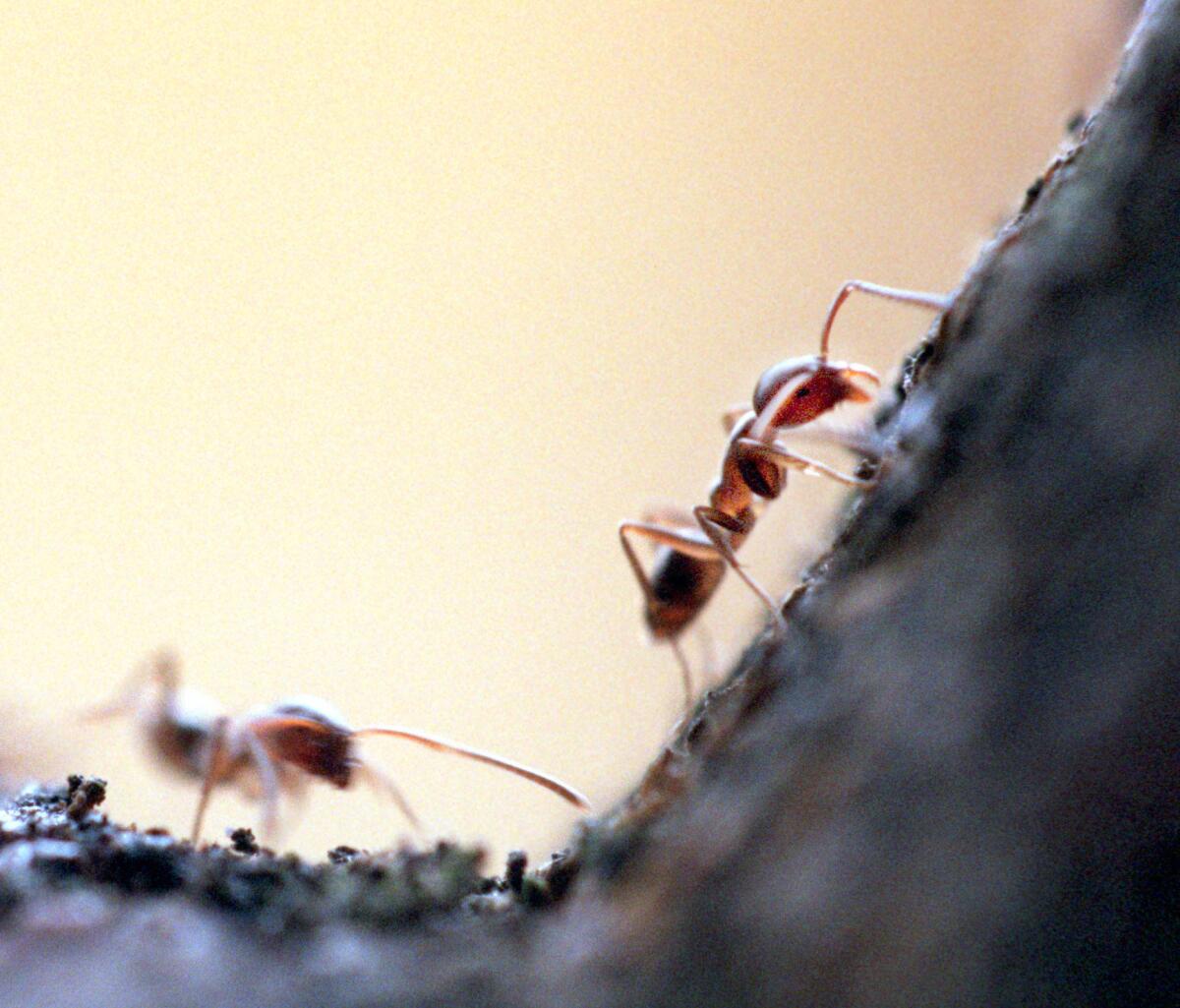

How ants’ amazing sense of smell controls their lives

Ants take social cues from each others’ body odors, a new study says. Their ability to smell tiny amounts of many different chemicals on each others’ bodies surpassed researchers’ expectations.

- Share via

Ants have a remarkably sophisticated sense of smell, allowing them to pick up odors that dictate how they behave and how they interact with each other, a new study says.

Each ant has a subtle, unique aroma, made from a blend of chemicals called pheromones stuck on the outside of its body. Minute differences in each ant’s body odor provide behavioral cues that allow the insects to maintain complex social colonies with different roles for queens, workers, nurses and soldiers — all without saying a word. Using exquisitely sensitive antennae instead of noses, they can even sniff out an intruder from another colony, according to a study published this week in Cell Reports.

“We are trying to decipher the language of chemicals that [ants] use to organize themselves into societies,” said Anandasankar Ray, an entomologist at UC Riverside and the research team leader.

Ray’s team began by putting Florida carpenter ants (Camponotus floridanus) on glass slides under a microscope and zooming in 1,000 times on their antennae, so they could see the hundreds of tiny sensory hairs that coat them. Next, they inserted a very thin glass electrode into a single sensory hair in order to record any biochemical activity on the insects’ antennae. In doing so, they were able to pinpoint the exact chemicals that ants could smell emitting from the queen, the workers and from ants from another colony.

“It was really surprising,” Ray said. “The ant was able to sense a very large number of [chemicals].” The ants’ sense of smell was so refined — much better than humans’, for example — that they could even distinguish between two molecules with the same chemical formula that differed “only ever so slightly.”

Ants’ ability to distinguish their colony-mates’ body odors is similar to a sommelier’s ability to sniff a glass of wine and tell the difference “between a Chardonnay and a Pinot Noir,” Ray said.

The ants were particularly good at sensing nonvolatile chemicals, which are notoriously hard to smell because they don’t easily evaporate and waft through the air the way some perfumes do. This is likely a clever evolutionary trait for insects living in such close quarters, Ray said.

“Imagine if you were getting into an elevator with a lot of people, and the only way you had of recognizing who you were interacting with was through your sense of smell,” Ray said. “It would be very difficult if everybody was wearing strong perfumes …. What [ants] have done is figured out a way to smell the very low-volatility compounds, so when they are in that elevator, they can only smell the person right next to them and be able to have an appropriate behavior interaction.”

Indeed, the chemical aromas the ants emitted determined how they acted toward each other. The queen, for example, produces “a cocktail of body odors,” which the rest of the colony can smell and which leads them to obey her, even to the extent of sacrificing their lives for her. “It’s a type of behavior control, or mind control,” Ray said.

The researchers tested the ants’ sense of smell by placing a tiny amount of two very similar chemical smells in a glass dish. When an ant went to a particular smell, the researchers rewarded it with sugar water. Even when the researchers moved the chemical odor associated with the reward to a new location in the dish, the ant was able to accurately find it.

“It’s just amazing they can do that,” said Grzegorz Buczkowski, an entomologist who studies ants at Purdue University who was not involved with the research. “They can tell the differences between chemicals and also between proportions of different chemicals.”

For more science news, follow me on Twitter @sasha_hl and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.