Atmospheric rivers fueled by climate change could decimate wild oysters in San Francisco Bay

- Share via

Climate change could supercharge the powerful storms often hailed for bringing drought-busting rains to California.

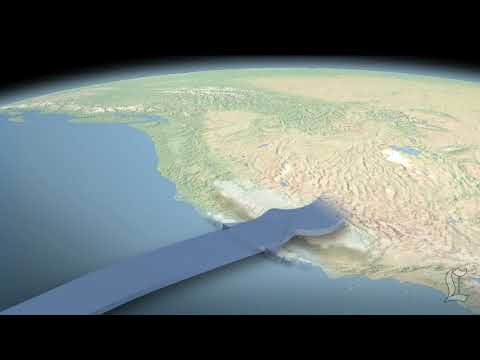

The storms, called atmospheric rivers, are long stretches of water vapor that travel from the tropics up to the West Coast of the U.S.. In California, they can deliver up to half of the state’s annual precipitation in just a couple of weeks.

But too much water at once can be a bad thing. The phenomena are capable of causing destructive floods and landslides — and now, according to a new study, ecological damage.

In March 2011, a series of atmospheric rivers contributed to a massive die-off of the struggling Olympia oyster population in the northern San Francisco Bay, according to researchers at UC Davis’ Bodega Marine Laboratory and the San Francisco Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve.

Their findings, published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, are the first to demonstrate the ecological effects of such storms — an example of the extreme climatic events expected to increase in size and frequency as climate change progresses.

See the most-read stories in Science this hour »

In California, climate models project that both intense droughts and floods, linked to strengthening El Niño and La Niña events, will increase by 50% by the end of the century. The reasoning is that warmer air can store more moisture and energy, which could in turn be unleashed in the form of bigger and badder storms.

While some ecological effects of climate change have been well-documented — such as warmer temperatures driving range shifts in plants and animal species — the impacts of extreme weather have proved difficult to study because of their unpredictable nature. However, scientists may have seen a preview of what’s to come over five years ago.

During the winter of 2010-11 — one of the wettest in almost 100 years — 20 atmospheric rivers hit California, building up snow in the Sierra Nevada mountains and filling reservoirs. In March alone, three of the rivers made landfall.

Atmospheric rivers are key to California’s rainfall.

On March 16, 2011, torrents of freshwater discharged into the San Francisco Bay from the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta. At its peak, 220,000 cubic feet of water rushed into the bay per second.

All that water diluted the bay, which caused low salinity levels that nearly matched the lowest threshold oysters can tolerate. For the oysters at China Camp State Park, one of the region’s biggest populations, the effect was catastrophic.

Just before the storms, study leader Brian Cheng, then with the Bodega Marine Lab, and colleagues counted about 180 oysters per square foot at the park. That was 30 times more oysters than the second-most populated site in the bay.

In the following months, the scientists observed dramatic declines in the mollusks’ population, finding decomposing oysters and gaping shells across the study sites. By July of 2011, almost all of the oysters had died.

Oysters match their internal salinity with that of their external environment. When the surrounding water gets less salty, they respond by sealing themselves up from the outside world. Olympia oysters can stay this way for about eight days until they asphyxiate or build up too much waste in their bodies.

By November 2013, the oysters at China Camp appeared to have rebounded to their pre-deluge numbers. Other populations around the bay likely provided the area with new “recruits” — larval oysters that float through the water until they find a hard surface to latch onto, allowing them to grow. However, the young oysters have yet to reach the same size as their predecessors, suggesting the population hasn’t fully recovered yet.

The once-abundant Olympia oyster, the West Coast’s only native species, has struggled for a century to recover from overfishing and habitat degradation since the time of the Gold Rush.

In the 1850s, the booming human population along the West Coast — especially in San Francisco — could not get enough of the little oysters, which have a coppery taste compared with the shellfish often served in restaurants today. Around the late 1800s or early 1900s, the fishery collapsed, and people began farming Pacific oysters introduced from Asia.

For many years, the San Francisco Bay has been the site of ambitious oyster restoration projects. Government agencies and environmental groups hope the filter-feeding, reef-building bivalves could protect the shoreline from erosion and sea level rise, as well as reinvigorate the underwater ecosystem.

“Mass mortality events may be a significant hurdle to the conservation and restoration of coastal marine organisms such as oysters, which are foundation species that provide numerous ecosystem functions,” the authors write.

Follow me on Twitter seangreene89 and “like” Los Angeles Times Science on Facebook.

ALSO

Hundreds of species are already going locally extinct because of climate change, study says

To mobilize Trump’s America for environmental protection, invoke the past

Sorry, Pokemon Go addicts, playing the video game doesn’t count as a real workout

UPDATES:

11:05 a.m.: This article has been updated with additional details from the study.

This article was originally published at 6 a.m.