Ex-Dodger Mike Marshall tries to repair his reputation

A key part of the Dodgers’ 1988 World Series-winning club, he was perceived as a whiner who wouldn’t play hurt. Now an independent league commissioner, he wants to get back to affiliated baseball, but the doors are not opening.

- Share via

On a summer night in a quaint ballpark nestled in thick pines and cool breezes, a crumpled piece of paper blows across the deepest part of center field.

No problem. A guy aimlessly dragging a large black garbage bag slips inside the center field fence between pitches, picks it up and keeps on walking.

Behind the dugout, the most famous man in Albert Park laughs. It has been 25 years, and he's cheerfully embracing the crazy soul of a sport that once tormented him.

This is independent league baseball, the Pacific Assn., the San Rafael Pacifics against the Maui Warriors, 1,200 people crammed into the stands at an ancient city park, buttery smiles and the scent of cooked meat everywhere.

One boy plays "Take Me Out to the Ballgame" on a ukulele. Another boy wins a contest by stuffing his face with a burrito at home plate. There is a whiffle-ball field back by the portable toilets. There are spectators sitting with the players in front of the dugout.

Beyond third base, a green hand-operated scoreboard records everything but balls and strikes because, well, it's just too darn hard to teeter atop that ladder for every ball and strike.

The most famous man in this wondrous place is so famous he actually has his name on the baseball being pitched by Eri Yoshida, Maui's 5-foot-1 female knuckleballer.

This is his league. This is his life.

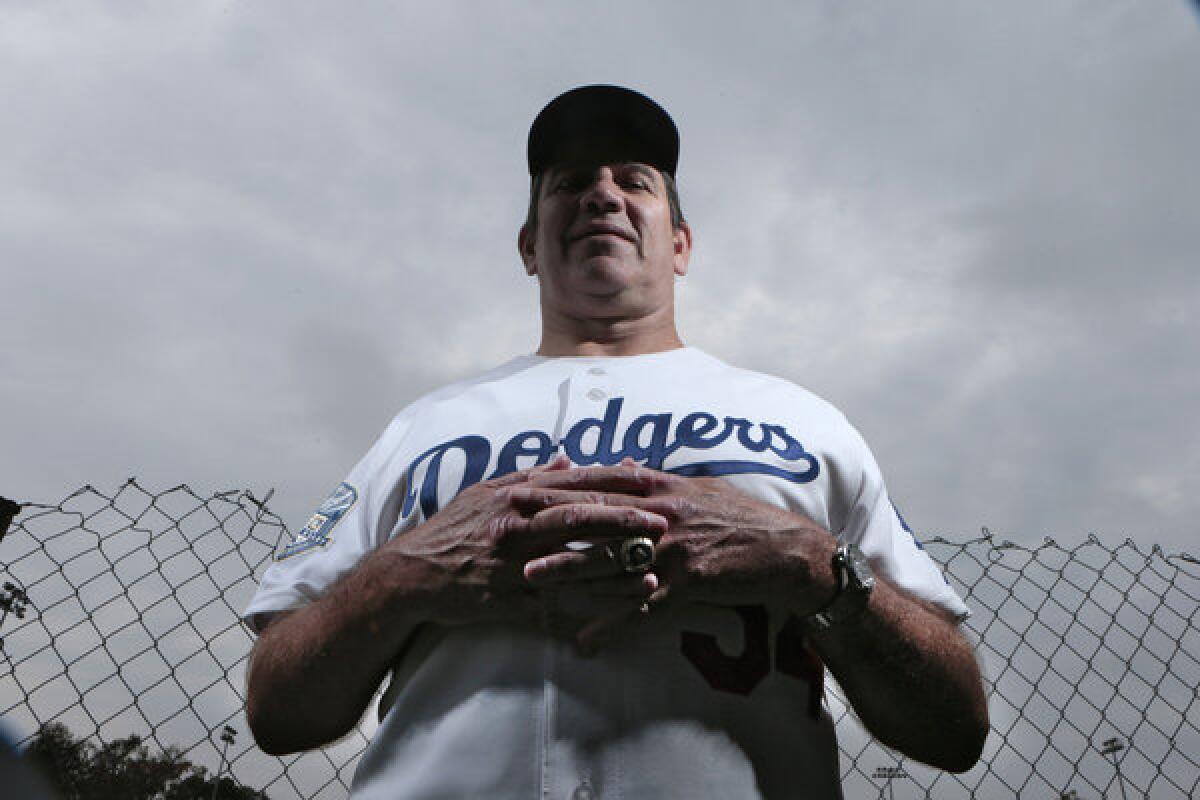

Mike Marshall, commissioner.

"Man, I just really love this game," Marshall says.

It was frustrating because this guy had all the ability in the world and didn't utilize it to the extent he should have."— Tom Lasorda, 1988 Dodgers Manager

Twenty-five years ago, many folks thought he didn't. Marshall was the right fielder and an integral part of the gritty 1988 World Series champion Dodgers, but he was perceived to be an enigma, the anti-Gibby, a star dressed in a shrug.

Marshall was ripped by the media and public for not playing hurt. He was attacked by his teammates for not being tough. He was even ridiculed by the Dodgers' media relations department when it was announced that he had been sidelined by, of all things, "general soreness."

When folks thought of Marshall, they thought of whining and wincing and how he once traded blows with Phil "Scrap Iron" Garner in the Dodger Stadium dugout runway. When they thought of Marshall in 1988, they grew particularly angry because his inability to overcome back pain and start Game 4 of the World Series led to the infamous proclamation that the Dodgers were fielding the worst lineup in World Series history.

"It was frustrating because this guy had all the ability in the world and didn't utilize it to the extent he should have," then-manager Tom Lasorda says.

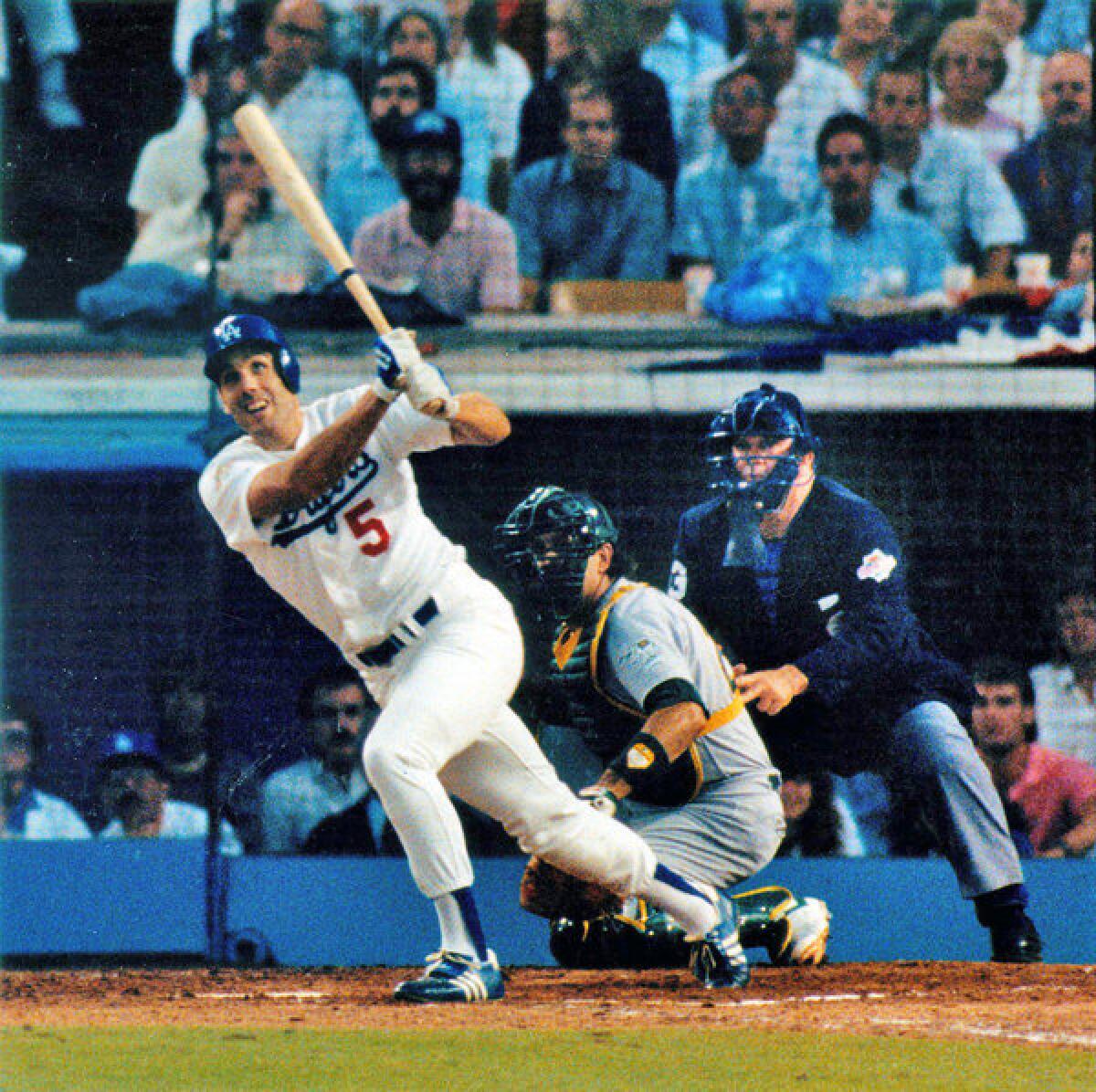

Yet people forget. They forget that Marshall led that championship team with 82 runs batted in, was second with 20 home runs, and ranked third with 577 plate appearances. They forget how Marshall's three-run home run in Game 2 of the World Series against the Oakland Athletics helped the Dodgers to a 6-0 victory. They forget his eight postseason RBIs.

Mike Marshall slugs a three-run homer in the second game of the 1988 World Series. The Dodgers won the game, 6-0. (Los Angles Times)

"I consider him an outstanding teammate, and I could not have accomplished what I did that year without him," Kirk Gibson says.

People forget so much that, 25 years later, Marshall has been all but forgotten.

He has spent the last 15 years working in all areas of independent baseball in hopes of showing affiliated baseball that he now understands toughness and teamwork. From Albany, N.Y., to Yuma, Ariz., he has done everything from washing jocks to raking fields to managing teams to, finally, running a league. He now works out of a tiny desk in the back of a storefront office as the commissioner of the four-team Pacific Assn., a job that involves everything from overseeing the umpires to driving the van carrying the visiting Maui team back to the San Francisco airport.

He has proven his love for baseball, but Major League Baseball has not loved him back. In his effort to return to the world where he once fueled a World Series title, Marshall has been shunned.

"I feel like that high school guy who always gets turned down when he asks for dates," Marshall says. "A lot of unreturned phone calls. A lot of rejection."

He has scoured the winter meetings looking for jobs. Nothing. He has called former teams looking for jobs — "Who are you again?"

I know I was not very well liked … I wish I had been tougher. I wish I had played."— Mike Marshall

On one of the several times he called the Dodgers, he says a team official wouldn't talk to him until he had seen a resume. Marshall immediately sent them a resume, yet never heard back. Ned Colletti, the Dodgers' general manager, said he is unaware that Marshall ever applied to his administration.

Actually, the Dodgers did reach out a couple of years ago. During a weekend when Marshall was in Los Angeles, he said he was asked to throw out a first pitch. Yet, a couple of hours before the game, he was told that the team was having a Latino-themed celebration, and that somebody else had been promised that pitch, and he was snubbed.

"I was like, of course, this figures," Marshall says with a grin.

He doesn't say it with bitterness, but understanding. Twenty-five years later, Marshall is open about his mistakes and honest about his remorse.

"I know I was not very well liked," he says. "I wish I had been tougher. I wish I had played."

Marshall was drafted by the Dodgers as a high school kid out of Libertyville, Ill., and by the time he was 21 he was hitting .373 with 34 home runs and 137 RBIs for triple-A Albuquerque.

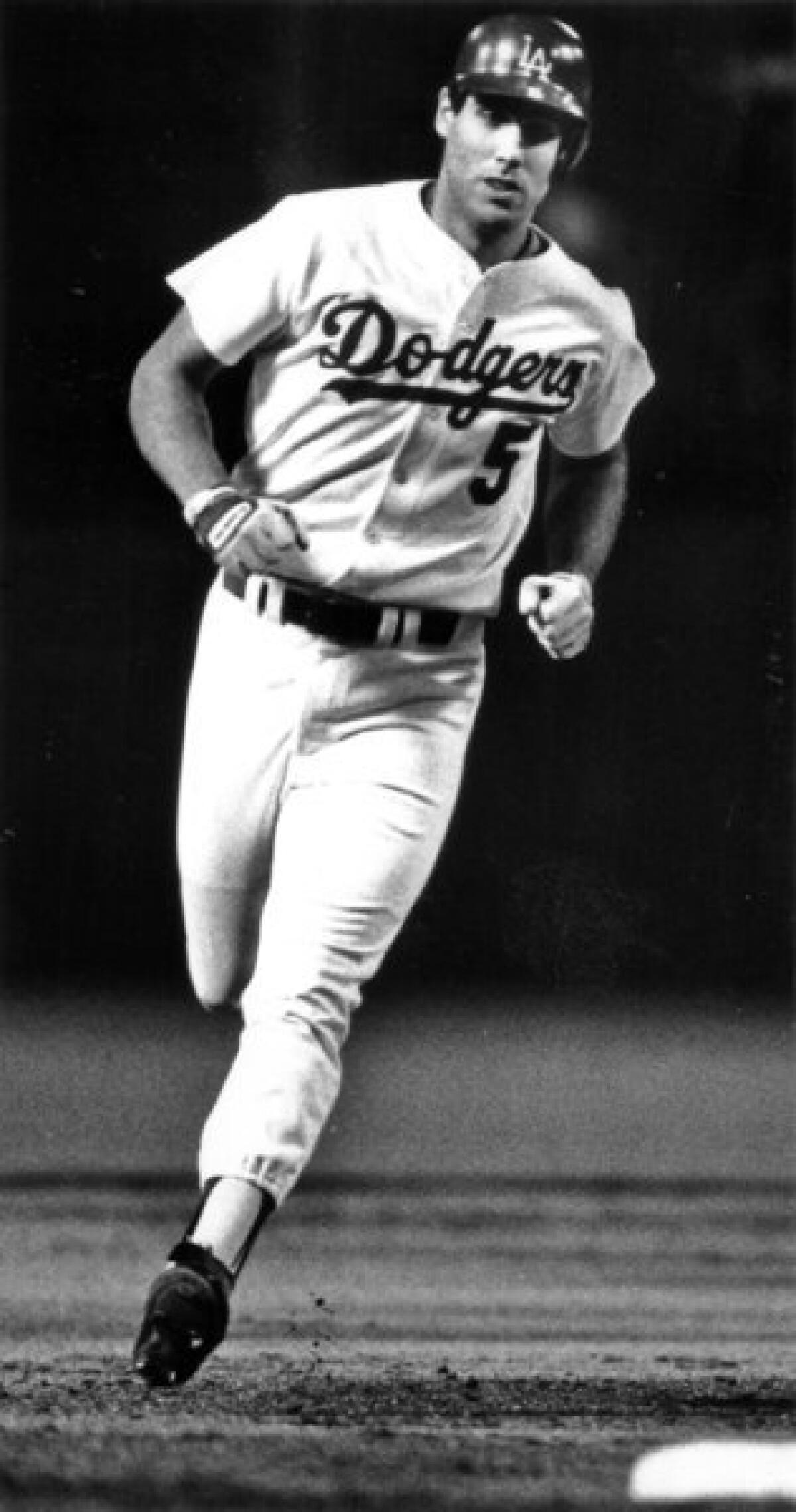

Former Los Angeles Dodger Mike Marshall rounds second base after hitting a second-inning home run. (Los Angeles Times)

Technically, his first full season with the Dodgers was 1983, but he never really played a full season. In the two years before the World Series-winning season, he sat out a combined 117 games.

It wasn't like he was just taking days off. His lanky 6-5 frame was always nicked or twisted in some fashion. The problem was that, while the long-season baseball culture demands that you play even when you aren't at full strength, Marshall could never fathom the idea.

"Some of my injuries, did I handle them perfectly? No, that was something I always regretted," he says. "I always wanted to be 100%. I always thought the team was better with someone else if I wasn't 100%. But, in hindsight, there are times I should have just rolled myself out there."

Now that Marshall has experienced all facets of the game, he understands where he went wrong. His voice trails off into a whisper and he slowly shakes his head.

"You're in your 20s, you're stupid, you make a lot of silly mistakes, a lot of silly decisions," he says. "You hate to have regrets, but, well, I have regrets."

When the Dodgers finished off Oakland to win the unlikely championship, Marshall said he felt more relief than joy. A year later, he was traded to the New York Mets, and two years later he had left affiliated baseball for good, retiring after playing his last game at 31, one of the potentially greatest Dodgers careers cut terribly short.

His 1988 World Series ring? He never wears it because, he says, it's painfully clunky.

"It just always hurt my finger," he says.

Several years after his early retirement, as if trying to erase that pain, Marshall returned to baseball. He heard about a job as a player-coach for the Schaumburg Flyers in an independent league near his Chicago home, and wanted to get back to his roots.

"I missed the game and thought I'd give it another shot," he says. "Turns out it was the greatest thing that ever happened to me."

All of a sudden, it all clicked in … This was my game. I had a purpose in this game. I was meant to do this."— Mike Marshall

It was certainly the hardest thing he has done, embarking on a journey that took him from Schaumburg to Albany to Fort Worth to El Paso to Yuma to Chico, Calif., to San Rafael. Along the way, he has been in the dugout, in the front office, in the league office, and in countless overheated buses and closet-size clubhouses.

He has managed games in front of 20 people in Hilo, Hawaii. He has managed games in 117-degree heat in Yuma. Yet, through this difficult devotion he has rediscovered a childlike joy in a game that once filled him with insecurity and overwhelmed him with pressure.

"All of a sudden, it all clicked in," he says. "This was my game. I had a purpose in this game. I was meant to do this."

The devotion worked for him, and it worked for his family. He and wife Mary, the Pacifics' assistant general manager, have been married 27 years. His two children, son Michael and daughter Marcheta, have graduated from Stanford.

Now, if it could only work to get him back to a major league organization.

"In view of the things that Mike has done in the game since his retirement, I think he deserves a better fate, a better image," says Fred Claire, the Dodgers general manager in 1988. "His love and devotion to the game has come back, and he's proven there should be a role for him a major league organization, no doubt.''

You want Mike Marshall's resume? It requires only eight words, spoken to him recently by wife Mary after watching him work another 16-hour day building a mound or draining a field or buying equipment or pitching batting practice or comforting a kid outfielder whose fears were once his own.

They are eight brutally honest words that chronicle a journey, seven words that have redefined a man.

"Mike," his wife told him, "I didn't know you were so tough."

Follow Bill Plaschke (@BillPlaschke) on Twitter

More on the 1988 Dodgers

His 1988 World Series 'minute' sustains Gilberto Reyes

For Tim Leary Dodgers' 1988 championship season never ends

I needed work. I needed to get better. I had to go to Tijuana.

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.