Derided Computer Plan Clicks With Maine Students

- Share via

KITTERY, Maine — In strong, direct terms, many Maine residents let Gov. Angus King know that his plan to provide laptop computers to every seventh-grader in the state was crazy.

“Dear Governor,” read one typical e-mail when King first floated the proposal almost three years ago: “This is the stupidest idea any politician ever had. What are you smoking?”

Undeterred by correspondence and legislative outcries that ran 10 to 1 against him, King proceeded with the “study in perseverance” that became the signature issue of a two-term, independent governor who reasoned that by using technology to raise education levels, Maine could build a better work force and thus strengthen its economy.

This fall, as 18,000 seventh-graders added Apple laptops in neat black cases to the school supplies they tote home each night, the missives to King’s office took on a new tone.

“Dear Governor,” wrote the mother of a child whose seizure disorders kept him from holding a pencil long enough to complete a spelling test: “I want to thank you for saving my son’s life.”

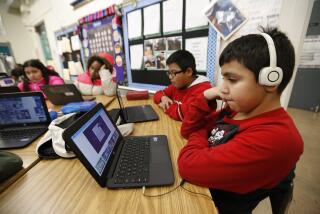

As school administrators such as Principal Gregory Goodness of the Shapleigh Middle School here lauded his state’s effort to “level the academic playing field,” the $37-million “learning technology initiative” made Maine the first state to offer universal laptop distribution to an entire grade of middle-schoolers. With the flip of a laptop “on” switch, Goodness and others asserted, students who live in rusty trailers stood on a tech par with classmates whose seaside mansions boast broadband connections and troves of software.

The ambitious plan to equalize learning opportunities for 12-year-olds is too new to have withstood standardized testing. But at a trial run last spring at one school in rural Washington County, absenteeism dropped 50% with the arrival of state-issued laptops. Pre-laptops, seventh-graders at Pembroke School received 28 detentions in 96 days. With laptops, the same students numbered just three detentions in 79 days. Using the laptops, 91% raised their grades in at least one academic area; 82% improved in two subjects; 73% in three or more fields.

“I was a skeptic at first,” said Goodness, whose school board passed a resolution two years ago opposing the laptop proposal. “But this really is changing the face of education.”

Educators from around the country -- as well as from Scotland, Canada and France -- have come to Maine to study the novel plan to boost computer literacy, instituted with foundation help from Microsoft Corp. Chairman Bill Gates. Early this month, a Texas company announced a software donation valued at $400 million to aid the pioneering program. Last week, native-son novelist Stephen King signed on as a volunteer online writing coach.

“One thing I want to remind you about this technology,” King, who is not related to the governor, told the state’s seventh-graders. “If you don’t like what I say, you can use the button that says ‘delete’ and make it go away.”

Poring over her pearl-white laptop, Shapleigh Middle School seventh-grader Jackie Ransome said she could hardly wait to ask the legendary horror author for advice about the story she was writing. In the fashion of many seventh-graders who speak in taut monosyllables, she barely looked up from her screen as she said: “I’m psyched.”

In an interview last week as he prepares to leave office in January, Gov. King said he realized a fresh leadership approach was needed as he suffered through a soporific session at a national governors’ conference three years ago. “Everybody was using the same formula: regulatory streamlining, tax cuts, investments in research and development,” King said.

“I had this clear insight that we were trapped at being 37th in per capita income.”

That same snowy winter of 1999, Maine woke up to a surprise budget surplus of more than $50 million. King decided to use the cash to help vault the state out of poverty by making it a leader in technology education.

“Dear Governor,” fumed an e-mail that summarily arrived at his office: “We are a poor state. Let someone else lead.”

“And we will stay a poor state,” King responded, “unless we lead.”

After a year of haggling, the state Legislature approved a $30-million endowment that staggers the initial apportionment of 36,000 laptops over two years. Foundation donations paid the difference for the $37-million contract with Apple Computer Inc.

This year’s seventh-graders will use the current batch of machines again next year, in the eighth grade, while the incoming seventh-graders will receive new Apples.

An annual outlay of $15 million to $20 million -- out of the state’s $1.8-billion school budget -- could keep the program going indefinitely, King said. He said that during a 15-hour special session Wednesday, in which lawmakers grappled with a $240-million budget shortfall, no one called for eliminating the laptop spending.

King said his office worked closely with Apple to ensure that the laptops were learning aids, not entertainment devices. Except for chess -- considered a mental discipline -- no games were installed, and none can be downloaded, said Jim Doyle, a King aide who oversaw the project. Students have limited e-mail access and cannot perform instant messaging. Music and pop culture sites also are restricted. Pop-up ads do not appear.

Essentially, the laptops serve as high-tech tools for writing and research, with students and parents promising in writing to adhere to the boundaries.

“I have a 12-year-old and I know how attractive these games can be,” King said. “I was not going to be the governor who brought 36,000 Game Boys to Maine.”

All 239 middle schools in Maine have been equipped with wireless networks, but laptop policies vary. Most districts let students use the laptops at home, after parents complete a short orientation course.

Students say transporting the computers is the closest thing to a problem -- not so much because they are cumbersome, but because the kids sometimes forget to zip their carrying cases. Still, boasted Shapleigh School seventh-grader John Wright, “I dropped mine three times and nothing happened.” His friend Nick Bartek glanced up to remark, “It’s a shock that they actually trust us with these things.”

Chafing at the notion of serving as a laboratory for educational innovation, some in the state of 1.2 million residents label the initiative a waste of time and, more importantly, money.

“We’re on our backs up here financially, and there are a lot of people who think this just doesn’t make a whole lot of sense,” said Mary Adams, a longtime tax activist from central Maine. “I don’t know how they’re going to use these laptops effectively to justify the expenditure.”

But the governor compares the critics to naysayers who rose up generations ago when schools talked about sending children home with other learning devices. “They said they could throw them at each other, or dump them in mud puddles and destroy them,” King said. “They were talking about books.”

Preparing to leave office in January and travel with his wife and two children on a long-promised Winnebago tour of the United States, King said he will use laptops to home-school his kids along the way. He also said he would not mind at all if laptops became the best-known legacy of his eight-year tenure.

“This is beyond anything we expected,” he said. “We wrought better than we thought.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.