Strike at elite India film school: Students take on politicians

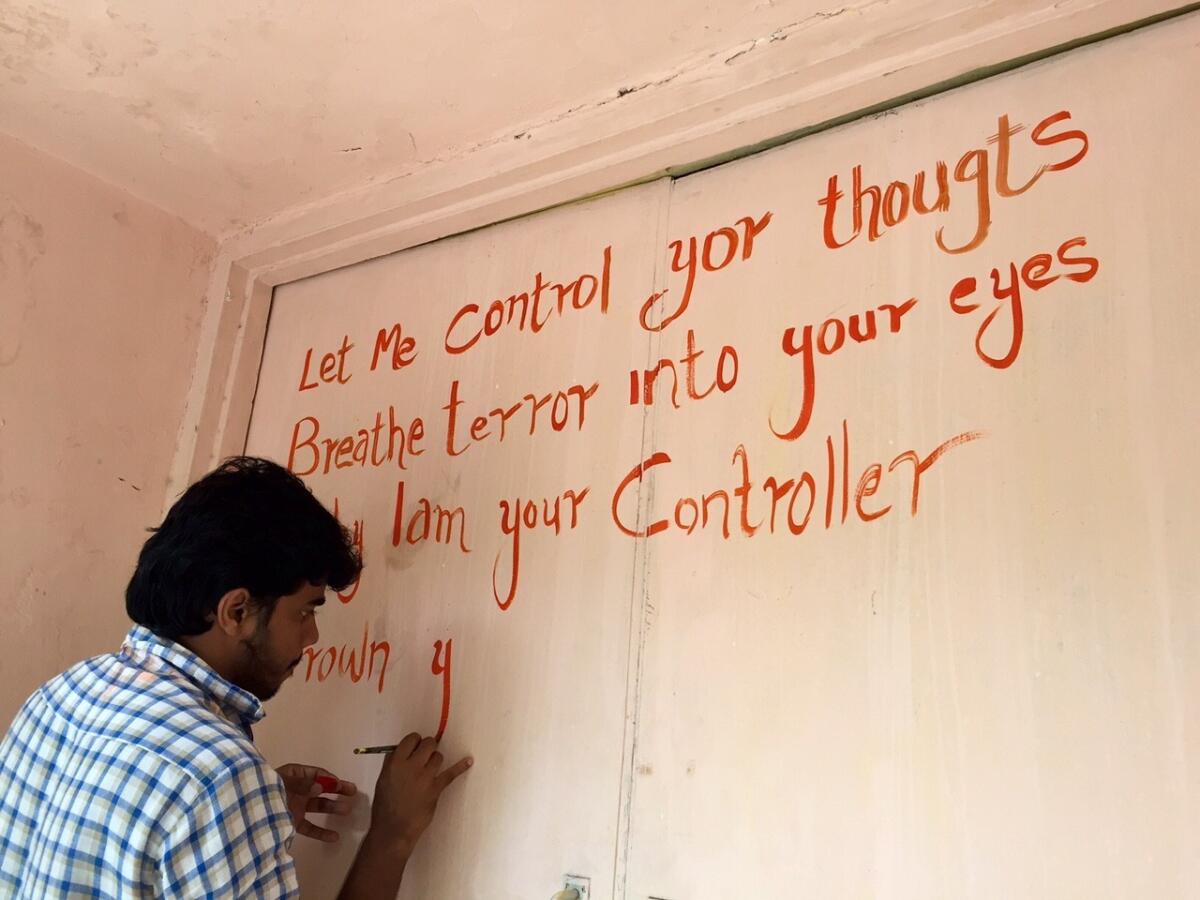

A student paints graffiti on a campus wall at the Film and Television Institute of India in Pune, where students have been on strike for nearly three months.

- Share via

Reporting from Pune, India — As battlegrounds go, the leafy campus of India’s premier film school must count among the more graceful, with its rows of tidy bungalows gently shaded by neem and tamarind trees.

Yet there is no mistaking the ferment at the Film and Television Institute of India. Hand-painted slogans snake across building walls, quoting Albert Camus and Martin Luther King. Outside the cafeteria, students in sweat pants and unkempt beards smoke hand-rolled cigarettes, talking of fascism and free speech.

For nearly three months, the roughly 400 students here have been on strike, protesting the Indian government’s appointments of loyalists with dubious credentials -- including an actor who appeared in B-grade adult movies and a maker of right-wing propaganda films -- to the state-funded school’s governing body.

“They want to turn FTII into a factory for their political views,” said Ranjit Nair, a directing student helping lead the protests. “We totally reject that.”

-----------

FOR THE RECORD

Aug. 26, 8:58 p.m.: An earlier version of this article misspelled Ranjit Nair’s surname as Naik.

------------

The skirmish is over not just the future of the foremost film academy in the world’s biggest moviemaking nation, a breeding ground for Oscar winners, expert technicians, darlings of the international festival circuit and stalwarts of Bollywood and India’s thriving regional cinema.

But it also represents the biggest showdown yet over Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s efforts to reshape India’s cultural institutions to fit his conservative, Hindu nationalist agenda.

During 16 months in power, Modi has packed the national censorship board with political supporters, named an obscure historian who believes in a literal reading of Hindu mythology to lead a prestigious research institute and created a government ministry to promote yoga and traditional medicine, including homeopathy and herbal remedies derived from Hindu scriptures, while cutting the country’s overall health budget.

“It’s obvious that these moves are connected,” said Jabeen Merchant, a film editor and FTII alumna. “Every government nominates people it likes; that’s inevitable. But this particular government is doing it in such a way that nobody can miss the agenda that’s being promoted.”

The confrontation escalated early this month after a group of students refused to let the institute’s director, Prashant Pathrabe, leave a meeting in his office late one night. They formed a chain and blocked Pathrabe’s door in a type of civil disobedience known as a gherao, or encirclement, a favorite tactic of Indian labor activists in the 1960s.

Police arrived to free Pathrabe, who filed charges the next day saying he had been subjected to “mental torture.” That night, police arrested five students who were later freed on bail.

Supporters of the strike accused police and administrators of overreacting, while those sympathetic to Modi’s government called the students insubordinate.

“They are not discussing with the government; they are trying to dictate,” said Uday Shankar Pani, a 1974 FTII graduate who was a first assistant director on Richard Attenborough’s “Gandhi.”

“They’re saying, ‘We don’t want anyone connected to your party.’ Hey, man, who are you talking to? The government is paying for this school.”

At the core of the dispute is the peculiar status of FTII, which is formally a unit of India’s Ministry of Information and Broadcasting founded in 1960 to train skilled workers for the country’s nascent film industry. The full-time professors are civil servants. On the campus in the bustling western city of Pune, everything is subsidized -- from the $1,100 annual tuition and fees to the cafeteria’s $1 chicken curry.

New Delhi’s view of FTII as a polytechnic school has long clashed with students’ creative aspirations. The school vacuums up national film awards, and its graduates include some of the leading lights of Indian film and theater, including actor Anupam Kher, director Shyam Benegal and Resul Pookutty, who won a sound mixing Oscar in 2009 for “Slumdog Millionaire.”

“FTII has contributed immensely to the flowering of both mainstream and art house Indian cinema,” said Indranil Bhattacharya, a directing professor. “Its place in the industry is extremely crucial.”

It has also developed a reputation as a hotbed of protests -- “‘One strike a decade’ is an unofficial FTII slogan,” a professor said -- although they never before spilled into national politics.

The latest agitation began in June, when Modi announced nominees to the FTII Society, from which the school’s governing council is selected. His choice for chairman was Gajendra Chauhan, a doughy, 58-year-old actor who appeared in a few sleazy, soft-core movies but is best known for playing a prince in a TV series based on the Hindu epic Mahabharata.

The other nominees included Anagha Ghaisas, producer of a fawning documentary about Modi subtitled “A Tale of Extraordinary Leadership,” and Narendra Pathak, who was leader of the local student branch of Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party in 2013 when its members assaulted FTII students who had invited a leftist cultural group to perform.

Pathak was quoted as saying of the protesters, “If there are mischief makers who work against the government, they should be taught a lesson.”

Chauhan has said he can solve the administrative crisis at FTII, which for years has admitted more students than its limited resources could support.

“Previous FTII chairpersons had almost no rapport with the government,” Chauhan told the Indian Express newspaper. His membership in Modi’s party would help him “get work done faster.”

Faculty say it is impossible to complete the syllabus in the prescribed three years, leading to a backlog of scores of students who enrolled as long ago as 2008 but have failed to complete their diploma films. Some continue to live rent-free in the dorms, whiling away days under the “Wisdom Tree,” a campus monument so revered it has its own Facebook and Tumblr pages -- both of which now provide regular strike updates.

The government’s latest proposal is to issue final grades to the 2008 cohort based on their existing work and force them to leave campus. Many professors oppose the plan, saying they can’t issue grades on half-completed films.

Students believe the government is trying to split the students, portraying the 2008 class to media outlets as lazy drug users who would rather strike than enter “the real world.” “They have called us every name: anti-nationalist, anti-Hindu, Naxals,” said one member of the 2008 entering class, Ajayan Adat, referring to an anti-government Indian guerrilla group. “We’re waiting for them to label us [Islamic State] and the Taliban.”

Lean and intense with a mop of curly hair, Adat’s path to FTII was like that of many students who can’t afford expensive private film schools in Mumbai, the heart of Bollywood.

He grew up without a television in a village in Kerala state, yet dreamed of becoming a sound engineer. To submit his FTII application, a friend helped him create his first email account. His father, a retired civil servant, borrowed about $8,000 to send him to the institute at age 19.

“People have this impression that FTII is an elitist institution,” said Adat, his voice hoarse from protests. “But I came here on a bank loan.”

Three years after he enrolled, when the loan was due, his father spent almost his entire government pension to pay it back.

“He has nothing now,” Adat said. “He’s hoping for me to get out and work, but still I’m here striking. And he’s worried, but he supports me.”

Adat and Nair were among 17 students for whom arrest warrants were issued for allegedly harassing the director. They surrendered to police and borrowed money to post bail.

A few hours later they were back on campus, amid the anti-government graffiti, the haze of cigarette smoke and the edgy tedium of a strike with no easy denouement in sight.

”The whole idea of dissent is built into this place,” Nair said. “It’s a creative environment. It’s only natural for us to stand up and ask these questions of the government.”

Special correspondent Parth M.N. contributed to this report.

Follow @SBengali on Twitter for news out of South Asia

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.