Bad drugs, unsafe surgeries: Deaths highlight India’s healthcare woes

- Share via

Reporting from Mumbai, India — India produces world-class doctors and lifesaving generic drugs, but the deaths last week of more than a dozen women who underwent sterilization surgeries have refocused attention on the less exemplary aspects of the country’s health system.

Activists have called for an end to the government-backed sterilization operations, a harsh form of population control still widely employed in rural India. The procedures are often carried out in assembly-line fashion at unsanitary and poorly equipped public “health camps” that result in scores of deaths every year.

------------

For the Record:

India sterilization: An article in the Nov. 16 Section A on India’s healthcare system incorrectly stated that between 2002 and 2012 an average of 12 Indian women a week died due to complications from tubal ligation surgeries. On average 12 women died a month.

------------

While the doctor who performed last week’s surgeries in impoverished central India is behind bars, authorities are also investigating whether women at the clinic were given antibiotics that contained traces of rat poison – underscoring how easily fake or tainted drugs can enter India’s health system.

Preliminary tests of pills handed out at the clinic in the state of Chhattisgarh found that they include zinc phosphide, a compound often used in pest control chemicals, officials said Saturday. Police have arrested the director of the drug manufacturer, Mahawar Pharma, a small, family-run company that supplies the state government.

State and local health officials continued to buy drugs from the company even though a court found in 2012 that it had sold fake generic medicines, The Indian Express newspaper reported Saturday. Chhattisgarh’s food and drug controller even gave Mahawar Pharma a certificate last year for maintaining “quality standards,” the newspaper said.

India exports $15 billion in pharmaceuticals annually, including 40% of the prescription medications used in the United States, but fake or faulty drugs are a major concern in the domestic market. There are no reliable estimates of the number of spurious medicines in circulation nationwide, but in a 2010 survey by nongovernmental organizations of pharmacies in the capital, New Delhi, 12% of drugs purchased were found to be substandard. Most contained either no active ingredients or nonlethal components such as chalk or talcum powder.

Cases of drugs tainted with poisonous compounds are rare, but when deaths are blamed on such drugs, authorities frequently arrest manufacturers to deflect attention from problems in the supply chain. The process of buying drugs is plagued by corruption and collusion between state-level officials – who are responsible for implementing health policies – and middlemen who secure favorable prices without regard for quality control, experts say.

“The government tends to buy from intermediaries because of cuts and commissions, and that is where the fault is,” said Bejon Misra, founder of the Partnership for Safe Medicines India, an advocacy group.

“It’s not that the states don’t have the budget. They have enough money to buy quality products – it is just their intent to prop up intermediaries for their own benefit.”

The effect of bad drugs is compounded, Misra said, when state health officials conduct mass clinics for procedures such as sterilizations, which often bring in hundreds of patients in quick succession.

Most of the 4 million Indian women who undergo tubal ligations every year – the highest number in the world -- are poor, uneducated and from rural areas. The “health camps” are heavily promoted by local health workers, often to meet quotas encouraged by state officials, critics say.

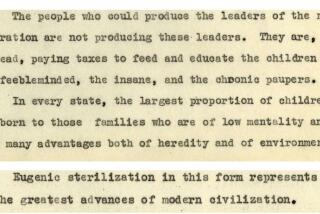

India, which launched a campaign of state-backed sterilizations under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi to curb population growth in the 1970s, has officially abandoned national quotas for the procedures. In reality, however, activists and patients say that state officials still set targets and offer cash and other incentives to lure patients.

R.K. Gupta, the doctor arrested last week for performing the surgeries on women in the town of Bilaspur, said that he was a “scapegoat” and faced pressure from supervisors to meet targets.

The state health minister, Amar Agarwal, denied setting targets but said the sterilization camps “are held in the interest of people, to keep the population in check” in a nation of 1.2 billion people.

Official statistics show that between 2002 and 2012, 1,434 women died due to complications from tubal ligation surgeries – an average of 12 every week. In 2012, three men were arrested in the northern state of Bihar for operating on 53 women in two hours in a field without using anesthesia.

Health officials say that Gupta performed more than 80 surgeries in six hours last weekend at the clinic in Bilaspur.

Aarti Gorwadkar, a doctor who has attended sterilization clinics in the western state of Maharashtra, said that basic hygiene procedures often aren’t followed. Surgical tools are rudimentary, doctors conduct only cursory evaluations before operating and women are sometimes left to recover on dirty floors.

Sometimes, she said, surgical implements aren’t sanitized before being used on the next patient, raising the risk of infections.

“I have seen them being cleaned in a hurry under running tap water,” Gorwadkar said.

Although vasectomies are a much safer procedure, few men are sterilized, owing largely to patriarchal traditions. Often, husbands pressure their wives to undergo sterilization to grab the cash incentives.

“Most of the time, women are kept in the dark about the details of the procedure and consequences of it,” said Abhay Bang, an activist in Maharashtra.

Many activists question why the surgeries are being performed at all, given India’s declining fertility rate. In 1971, the average Indian woman had 5.1 children, but that rate has fallen to 2.4, just above the level at which a population stabilizes.

Yet growth rates remain relatively high in India’s poorest areas, such as Chhattisgarh, where sterilization drives continue.

“It cannot be a coincidence that the more prosperous regions of the country have less fertility rates,” said Kiran Moghe, secretary of the nongovernmental All India Democratic Women’s Assn. “The challenge before the government is to raise the standard of living of the poor districts and not indulge in short-term goals like sterilization.”

Special correspondent Parth M.N. reported from Mumbai and Times staff writer Bengali from Kabul, Afghanistan.

For more news from South Asia, follow @SBengali on Twitter

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.