Long forgotten, a star of prewar Germany is rediscovered more than 70 years after his death at Auschwitz

- Share via

For a time, Max Ehrlich got to live his best life: He was married to a woman he loved; he was one of the world’s most sought-after cabaret actors and composers, performing with the likes of Marlene Dietrich; his books were international best-sellers.

Famous from Berlin to Los Angeles, his cheerful, fleshy mug was recognized around the world, like a Milton Berle or Stephen Colbert of his time.

But celebrity is no shield against misfortune.

When, late in 1944, he was deposited at the Auschwitz death camp, a Nazi captain familiar with the Berlin club scene recognized him, pulled him aside, positioned him in front of an SS firing squad and ordered that he deliver jokes or die.

“We have many eyewitness testimonies of this. People remembered this event specifically,” said a spokesman for Yad Vashem, the Holocaust museum in Jerusalem.

Ehrlich survived the little game only to be killed in Auschwitz’s gas chamber on Oct. 1, 1944, at age 51, alongside his friend, collaborator and fellow cabaret superstar Willy Rosen.

His story could have ended there, were it not for the tireless work of a nephew, Alan Ehrlich, who was born in New York seven months after Max’s death. As a tribute to his father, Max’s younger brother Herbert, Alan Ehrlich has devoted decades to saving the story of his uncle from oblivion.

His efforts will culminate Sunday, when two of Max Ehrlich’s long-lost songs will be performed at a concert in Jerusalem, “Notes of Hope,” marking the 70th anniversary of the founding of the state of Israel.

Almost no one remembers Max Ehrlich today. But in his time, before the Nazis erased Jews from public life, he was a giant of stage and screen, known for his elegant satire. He thrived in the anything-goes cabaret scene of prewar Berlin.

The change came in the early 1930s, with the rise of the Nazi party in Germany. In 1933, Ehrlich accompanied the great Berlin cabaret composer Rudolf Nelson to Vienna. As soon as Ehrlich took the stage, the hissing and jeering started. Within seconds, hooligans were yelling, "Jews out! Jews out!"

The show closed. The troupe fled.

His glittering film career, including more than 40 movies in which he is credited as an actor, director or screenwriter, abruptly ended that year.

In July 1937, Max and his wife, Charlotte, left Berlin for New York, seeking opportunities far from Nazism. They reunited with old friends including actress Eva Ortmann and her husband, Fritz Lechner, an opera singer, who had been in America since late 1936.

On Aug. 3, 1937, Ortmann wrote a letter to her daughter, Sybille, who was safe in London.

“My darling,” she began. “We spent a recent evening with Max Ehrlich, the comedian from Berlin. He is currently still in the Kulturbund and is only here to get to know the place. He plans to return [to Germany] because he leads the entire cabaret and doesn’t want to leave the troupe in the lurch.”

The Jüdischer Kulturbund, popularly known as KuBu, was an association of German Jewish artists established by the Nazi government in 1933, when Jews were banned from performing for non-Jewish audiences. At its height, it employed some 180,000 people, and Max, one of its top names, was deeply committed to his fellow artists.

“Next year,” Ortmann continued, “he wants to open a German cabaret here in New York as he believes there’s a big enough audience.”

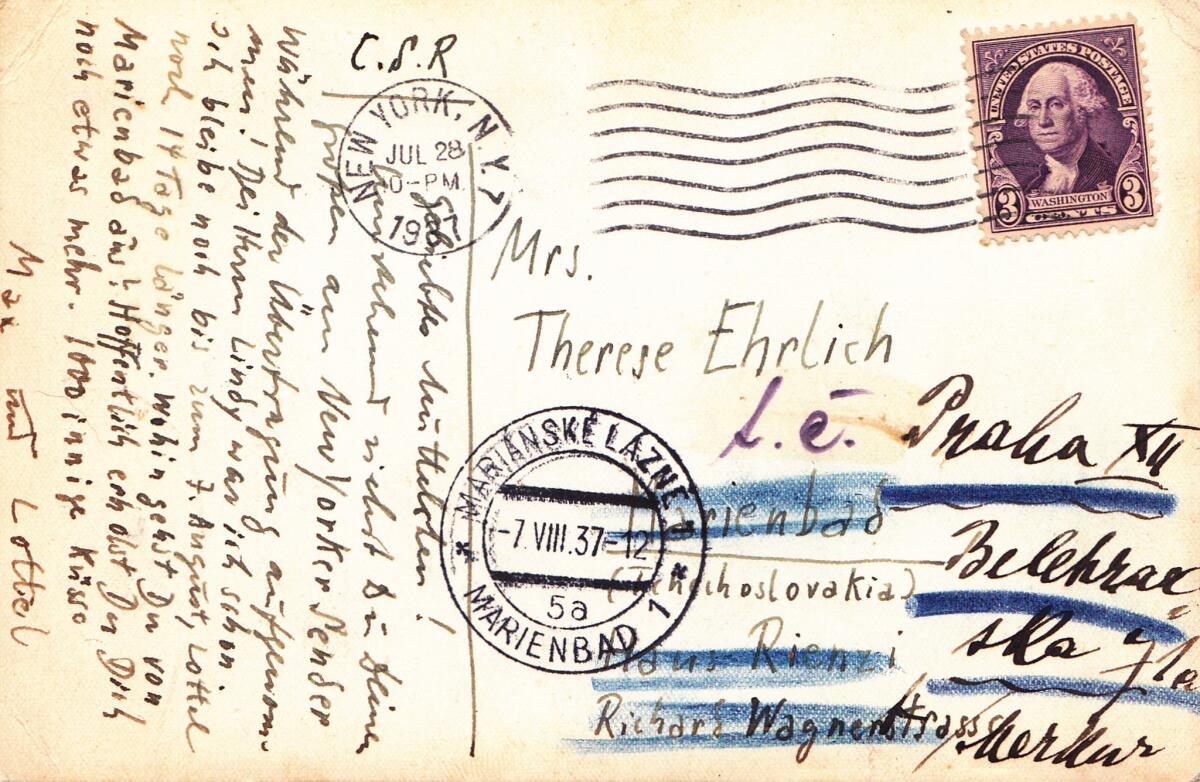

Max sent relatives exuberant postcards with pictures of him performing at a New York radio studio with what appears to be a full orchestra. One card went to his mother, Therese, at an address in Marienbad, a Czech spa town.

“Beloved mommy, On the other side you can see your son at the New York radio station, a picture taken during the broadcast. I’ve already been to Mr. Lindy’s [presumably referring to the famous Lindy’s deli]. … 1,000 loving kisses.”

Friends urged the Ehrlichs to stay in America, but Max had KuBu commitments. They set sail back to Europe in August 1937.

In November 1938, the Nazis carried out the outburst of murderous violence known as Kristallnacht, auguring the Final Solution, and prompting Ehrlich to resolve to leave Germany. His final Berlin appearances were boisterous, sold-out events, the audience begging for more.

With few options available, he headed to Amsterdam, where he had led the cast of a popular revue in 1934.

In 1940 the Nazis invaded Holland. As normal life became untenable, Ehrlich reached out to his second cousin, Ernst Lubitsch, by then a celebrated Hollywood director and producer. The two had been childhood playmates and then classmates at Max Reinhardt's seminar at the elite Deutsches Theater. Lubitsch had left Germany in 1922 when he was hired by Mary Pickford to direct the hit “Rosita.”

But at some point, Lubitsch and Erhlich had a falling-out. “Is he maybe angry with me?” Ehrlich asked in a March 1941 letter to Trude Lubitsch, a mutual cousin.

In November 1941, he wrote again to Trude Lubitsch, this time sounding more desperate and using an alias he had adopted for safety: Peter.

“We sit here and don’t know what will happen to us. We’d hoped that on the other side [America] something would happen with our immigration…. Something has to be done now, immediately before it is too late! Maybe Ernst is no longer angry and we can ask him for help? ... If nothing happens, there is hardly any hope that Peter will ever see you again.”

On Nov. 18, 1942, according to a Red Cross certificate issued a decade later, the Ehrlichs were rounded up with other Amsterdam Jews and taken to Westerbork, a Nazi camp deep in the Dutch countryside.

There, the uncanny happened. For 22 months, Max Ehrlich, along with Rosen, wrote for, conducted and directed the Westerbork Theater Group, an ensemble consisting of some of Europe’s most renowned performers, suddenly playing for their lives.

The camp commandant, Albert Konrad Gemmeker, was “starstruck,” Alan Ehrlich said. “He suddenly had a Hollywood cast at his disposal.” Gemmeker kept the names of members of his personal theater company off the lists of inmates heading to extermination camps so he could entertain other SS officers.

“The lives of the people in that crew depended on their ability to put on a good show,” Alan Ehrlich said.

In late 1944, sensing that the end was coming, Max Erhlich handed an envelope containing his final works to one of Westerbork’s few visitors: the 18-year-old-son of Jetty Cantor, once a leading light of the Amsterdam stage, then a fellow inmate at the camp.

Ehrlich had been right. The end came within months.

Jetty Cantor survived the Holocaust and returned to postwar stardom. All of Ehrlich’s brothers survived — one in Havana, one in Paris and one, Herbert, in New York. Max’s wife, Charlotte, survived Auschwitz and supported herself as a masseuse in Los Angeles until her death in 1978.

At some point, Herbert’s son Alan began digging into the story of an uncle he had never known.

“Mostly, it had to do with my father,” he said during a recent visit to Westerbork, a desolate site in which only one original building — the commandant’s house — still stands. “Max was the one dark thing in his life. The only thing that he felt he had failed at and had wanted more than anything was to bring his brother to America, to save him, and that left a mark on me as well.”

Alan set up a website, max-ehrlich.org, where he documented whatever he could find. He hopped on planes at the drop of a hat to explore unexpected tips. But one remote possibility always tugged at him: What if a part of Max’s very public life had never been publicly known?

One day, Ehrlich ran one of his regular internet searches for “Max Ehrlich” and a new item came up on a Dutch theater community website. Someone posted that a newly located file had been deposited at the Theater Institute of the Netherlands.

“I flew there immediately,” said Ehrlich, who lives in Geneva and is a retired organizational psychologist. The file had been found months before, and contained the script that Max Ehrlich had turned over to Jaap Cantor, the young son of his fellow inmate at Westerbork. Fifty years later, nearing retirement, Jaap Cantor was about to throw out the envelope when a neighbor encouraged him to turn it over to the Theater Institute.

“I was able to confirm that it was Max’s staging notes on the script, in his handwriting using green fountain pen ink, just like he used in the letter to my father,” Alan Ehrlich said.

“Totally Crazy” is the apt name of the cabaret that Alan Ehrlich discovered that day. It was his uncle’s final, unknown revue, whose premiere and sole performance was in June 1944, on Westerbork’s stage.

The papers divulged the existence of the show, but there was a catch. “The file solely contained words,” Ehrlich said. “No music at all. Not one note.”

“The music at that point became my biggest mystery,” he added. “How do you pull music out of the air?”

He had help, first from Katja Zaich, the world’s foremost expert on Jewish exile theater in Holland. The title of her book, “I Urgently Request a Happy End,” is taken from one of the last lines Max Ehrlich ever uttered onstage.

Zaich introduced Ehrlich to Louis de Wijze, who, half a century earlier, had been a talented young amateur member of the Westerbork Theater Group.

De Wijze remembered about half the songs. Zaich and Ehrlich then joined forces with Francesco Lotoro, an Italian musician who has dedicated 30 years to recovering music lost to concentration camps. He called it musica concentrazionaria.

Working only with his wife, Grazia, Lotoro had created Last Musik, an institute he has self-funded for three decades, with a repertoire of 4,000 papers and 13,000 microfiches of music sheets, letters, drawings and photos. He has self-published five CDs of music, including works produced by Gypsies held by the Nazis and that of Dutch prisoners interned by the Japanese in Indonesia.

“In the Ehrlich case,” Lotoro said, “we had to find the music out of nothing. Out of air.”

Based on the cabaret script and De Wijze’s a cappella singing from memory, Lotoro recreated about half of “Totally Crazy,” some of which will be heard for the first time at the Jerusalem concert.

“Hearing this music means new life,” said Samuel Hayek, chairman of the British charity Jewish National Fund U.K., who is organizing the concert, in which high school musicians will play alongside the Symphony Orchestra of Ashdod. “I can’t think of a better celebration.”

The Jerusalem audience will hear Tatata, a jaunty, legs-lifted-high cabaret tune. It includes the words: “This must be a hit! I commend it / You cannot fail / because the text and music are mine. Tatata, this tune / Tatata, you never forget!”

Tarnopolsky is a special correspondent.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.