- Share via

Sandra Ruiz thought nothing of it when a man and his 8-year-old daughter walked into her intro to computer science course.

After all, working parents were nothing new at Crafton Hills College in Yucaipa.

“I thought, ‘Here comes a dad — the student — and his daughter,’” the veteran assistant professor said. “I thought he was in need of a babysitter.”

Imagine her surprise when it turned out she had it backward.

Right before class began, Rafael Perales departed — leaving his daughter, Alisa, to begin her second semester of college.

“It was my first time I had ever had a student so young,” said Ruiz, who taught Alisa for two semesters and served as her programming coach. “It turned out she was quite an amazing student who brought a level of focus and creativity that made her stand out as much as her age.”

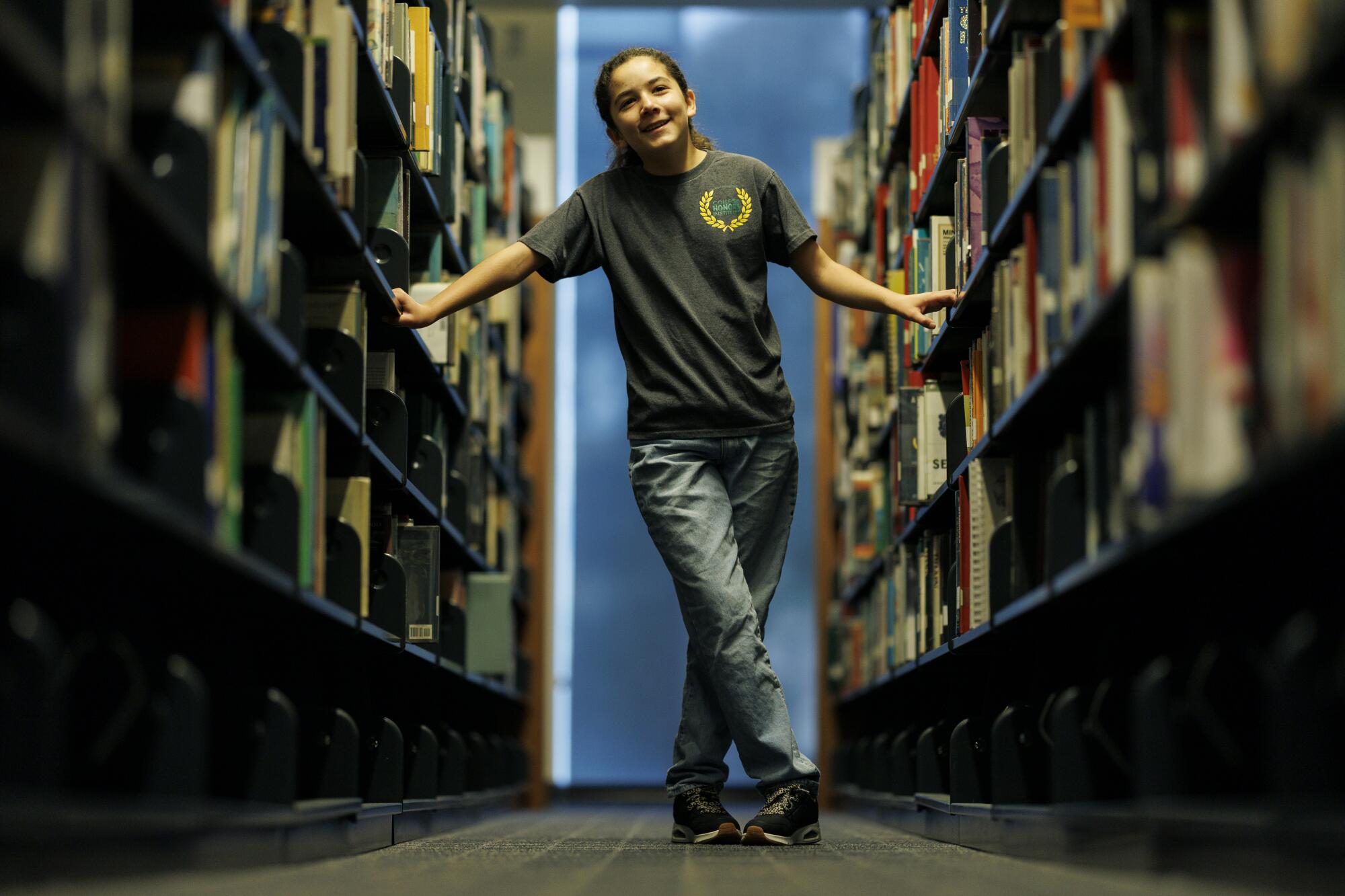

Far from just standing out because of her youth, Alisa proved to be a standout student. Over 2½ years at the college, she posted a 3.8 GPA.

Now 11, she graduates Friday with associate degrees in multiple sciences and mathematics. She is the school’s youngest graduate and among the youngest in California state history.

Up next is a university — she’s already been accepted to a few University of California campuses, though she hasn’t yet decided where she’s heading this fall. Eventually, the tween dynamo dreams of working with artificial intelligence at aerospace giant SpaceX.

“It’s a really exciting time to be graduating and preparing for my future,” Alisa said.

The path toward the graduation stage started a decade ago, when Perales noticed his daughter’s natural academic prowess.

“I wanted to see what my kid could do with full-time attention and learning,” Perales said. “It wasn’t an easy choice, but she was worth it.”

A civil lawyer by trade who is divorced and raised his daughter alone, Perales quit his burgeoning practice to become Alisa’s instructor.

The duo treated learning like a profession, studying eight hours a day, six days a week.

“I worked hard from the beginning till now,” Alisa said. “I felt like I was a natural at the work, at learning, but it was still a lot of hard work.”

By her 2nd birthday — when most children are expected to recognize basic shapes and colors and converse in short two- to four-word sentences — Alisa had already mastered the alphabet and could count into the hundreds.

At 2½ years old, she could read on her own. By 3, she was writing with upper elementary school precision, had conquered multiplication tables and understood division, her father said.

“I had to buy her larger, thicker pencils she could hold in her hands to do the work,” he said.

Alisa moved onto long division by age 4 and basic algebra by the time she was 5.

Perales said he eschewed more established public and charter schools, feeling they wouldn’t offer the same rigor he could. He couldn’t afford private schools or tutors, and balked at home-schooling formats and curricula for his daughter, feeling he knew his child best.

He received his educational training from what he calls “YouTube University,” mixing in do-it-yourself tutorials and educational entertainment such as the Busy Beavers language skills videos with old-fashioned staples such as flash cards and coloring books.

“I wanted something out-of-the-box for my daughter and I tailored the learning just for her,” Perales said.

Perales said the shift from earner to educator came with a massive economic hit that left him “scraping by for many years.” Father and daughter subsisted on a few real estate investments that allowed him “to pay the bills.”

But the work paid off. By 8, Alisa had completed all the coursework mandated by the state to graduate from high school with a diploma.

“She obviously had some innate spark that really drives her to excel, but she has put in the time,” Perales said.

It wasn’t all hard work, though. Between the ages of 4 and 8, Perales scaled back — reducing classroom time to five days a week.

Wanting to reward his daughter, Perales bought a Disneyland season pass and took Alisa to the Happiest Place on Earth every weekend.

There, she found joy noshing on chicken tenders, turkey legs and Mickey Mouse cookies.

While the scientific part of Alisa’s mind wondered how many cast members were necessary to operate her favorite ride — Star Wars: Rise of the Resistance — the rest enjoyed the drops, dark turns and ultimately successful escape.

As graduation day drew closer, however, her path to this point also drew some backlash.

You might already have heard of Michael Kearney, who moved to the San Fernando Valley last year after graduating from college.

Crafton Hills College put out a statement April 16 touting Alisa’s accomplishment. But after the news was picked up by media outlets, some online commentators pushed back — telling Perales to “let children be children,” or questioning what the end goal was.

To Perales, the criticism from strangers was as surprising as it was off base.

“She runs into the crowd of kids and makes new friends and everybody is having a great time instantly,” he said. “Everything that people feared about her being awkward or unsociable was completely wrong.”

Alisa said she plays soccer with friends in her San Bernardino neighborhood, often racing to find them at a local park once she’s finished with her schoolwork.

She also connects with pals over the online video game platform Roblox.

Making friends can be challenging for children and their parents no matter the circumstances.

The University of Michigan’s C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital released a poll last year in which they sampled parents of children ages 6 to 12.

Almost 1 in 5 parents surveyed said their child had either no friends or not enough. In that same poll, 21% of parents said shyness or social awkwardness had stunted their kids’ ability to make friends.

Alisa, for her part, says she would introduce “myself to kids my age, start talking and asking when they were available to play. That’s how I made new friends.”

A 12-year-old boy who is graduating from Fullerton College with five degrees, said he’s interested in careers in commercial piloting and aerospace.

Alisa’s first year at Crafton Hills was a mix of nerves and excitement.

“It was nice meeting new people there from the first day on,” she said. “Everything was new, but semester after semester, I was getting more and more comfortable there.”

Perales bought a pair of walkie-talkies so he could communicate with his daughter on breaks and in between classes.

He sat directly outside her class as the then 8-year-old student began her collegiate career. After the first year, he waited down the hall and eventually outside buildings, in school courtyards and off campus.

In college, Alisa studied 35 hours a week independent of the coursework, according to Perales. While enrolled, she was also a contributor on the school’s programming team that Ruiz, her computer science instructor, helped coach.

The 15-member squad competed in the International Collegiate Programming Contest Southern California Reigonal at Riverside City College in November.

Students competed to solve sets of programming problems in three-person teams over a 12-hour day. Ruiz said that Alisa was easily the youngest participant there.

“She worked so confidently alongside the older students while there was no one even close to her age,” Ruiz said. “Just watching her problem-solve under pressure and seeing how her teammates looked to her for ideas was incredibly inspiring.”

Not content with just accelerating her high school and collegiate career, Alisa also tried to get a jump start on another activity usually reserved for those older than she: voting.

Jack Rico, who earned his bachelor’s degree in history, says he wants to aim for a master’s degree next.

In April 2023, she sued California and the federal government, arguing that the 26th Amendment — which lowered the national voting age from 21 to 18 — constituted age discrimination. Her father served as counsel.

Alisa said she was inspired to challenge the amendment during her political science class, the lone college course in which she did not receive an “A.”

She argued she should be allowed to participate in democracy, and that her high school education and enrollment in Crafton Hills’ College Honors Institute proved she was more than competent enough to vote.

A U.S. Central District Court judge was not swayed, and dismissed the case in January 2024.

Pamela S. Karlan, co-director of the Supreme Court Litigation Clinic at Stanford University, agreed that voting-age laws discriminate on the basis of age.

However, she noted in an email to The Times that the Supreme Court has repeatedly held that the government may do so as long as “the age classification in question is rationally related to a legitimate state interest.”

“As long as there’s some basis to treat people differently based on their age, the law stands,” she said.

Perales said he and his daughter will not appeal the decision due to the prohibitive cost.

“I might not be the person to change the law but maybe someone else will pick this up and challenge,” Alisa said.

That can wait, anyway. She has a cap and gown to get ready.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.