One Mexican town revolts against violence and corruption. Six years in, its experiment is working

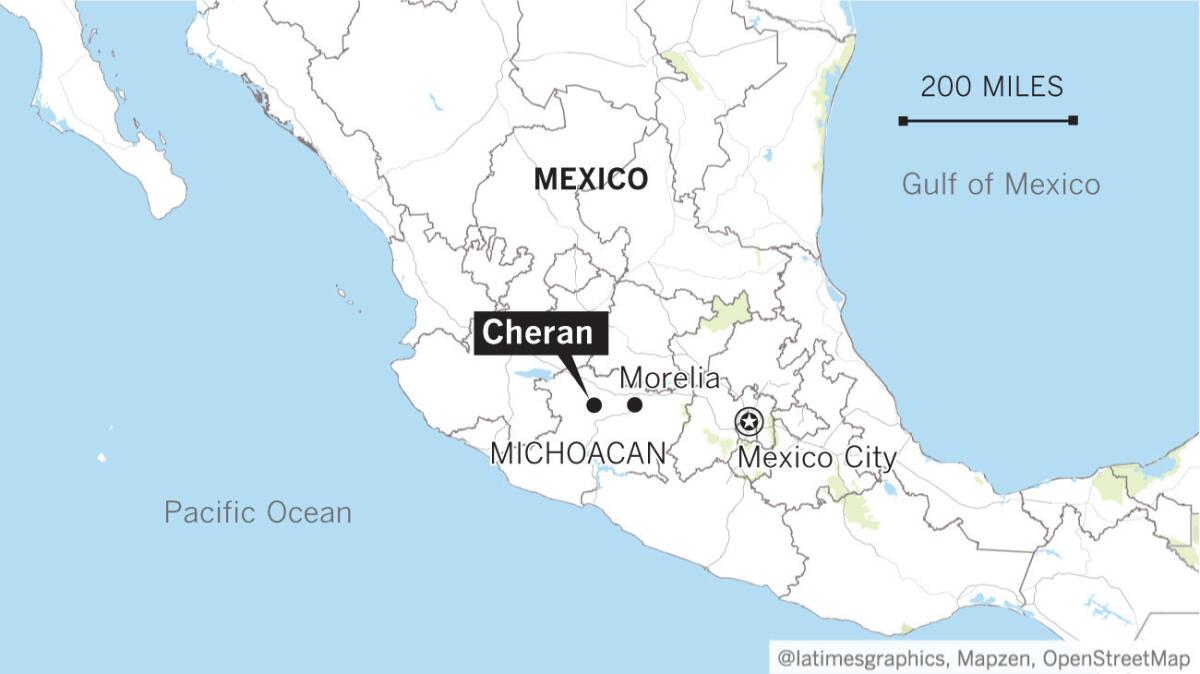

The town of Cheran in Mexico’s Michoacan state has thrown out politicians, cops and the mayor to relieve itself from violence and illegal logging.

- Share via

Checkpoints staffed by men with assault rifles, camouflage and body armor greet visitors at the three major entrances to this town.

The guards are not soldiers, police officers, drug enforcers or vigilantes. They are members of homegrown patrols that have helped keep Cheran a bastion of tranquillity within one of Mexico’s most violent regions.

The town of 20,000 sits in the northwest corner of Michoacan, a state where authorities say at least 599 people were killed between January and May, an increase of almost 40% compared with the same period last year. Cheran hasn’t had a slaying or other serious crime since early 2011.

That was the year that residents, most of them indigenous and poor, waged an insurrection and declared self-rule in hopes of ridding themselves of the ills that plague so much of Mexico: raging violence, corrupt politicians, a toothless justice system and gangs that have expanded from drug smuggling to extortion, kidnapping and illegal logging.

Six years in, against all odds, Cheran’s experiment appears to be working.

“We couldn’t trust the authorities or police any more,” said Josefina Estrada, a petite grandmother who is among the women who spearheaded the revolt. “We didn’t feel that they protected us or helped us. We saw them as accomplices with the criminals.”

Indeed, the criminal syndicates that have long dominated Michoacan are part of the reason, along with rampant poverty, that Cheran and other rural areas in the state have sent so many immigrants to the United States.

Cheran’s scourge were the talamontes, illegal loggers who worked at the behest of larger mafias and raided the communal forests that are vital to its economy and culture.

The timber thieves would parade through town on hulking trucks, ferrying illegal loads of pine, brandishing weapons and threatening anyone resisting.

Rafael Garcia Avila resisted. He belonged to a town committee that monitored forest use and had taken a stand against illegal logging. He and a colleague were kidnapped by gunmen on Feb. 11, 2011, and never seen again, joining the multitudes of “disappeared” who have vanished during Mexico’s war on drugs.

“My husband loved the forests, the woods, the natural world,” recalled his widow, Maria Juarez Gonzalez, tears welling in her eyes.

The disappearances — along with other killings, assaults, threats, and the plunder of the town’s ancestral forests — became unbearable in a community whose residents retain their identity as Purepecha Indians, one of the few indigenous groups in the area that did not succumb to the Aztec empire.

“The talamontes would drive by in their trucks, laughing at us,” recalled Estrada, a mother of eight — six of them living in the United States — who sells health shakes from a small storefront. “It wasn’t safe to be out at night. It wasn’t safe to be in the forest…. Sometimes I went home and cried and cried.”

Finally, she called some other women and decided to strike back.

On April 15, 2011, before dawn, the people of Cheran sounded the bells at the Roman Catholic Chapel of the Calvary and set off homemade fireworks to summon help. Few had firearms, so they brought picks, shovels and rocks.

Then they struck, seizing the first timber truck of the day, dragging its two crew members from the cab and taking them hostage. Lacking rope, they tied up their prisoners with rebozos, or shawls.

As more people responded, an initial crowd of about 30 swelled to more than 200.

Residents dug ditches and placed timber barricades to block entry to the town. As the sun went down, the people of Cheran set tires ablaze and lit campfires to ensure no one would pass.

Eventually, they took five loggers hostage and torched seven of their trucks.

The gangs retreated and hostages were returned.

But the revolt lived on. Known simply as the “uprising,” it entered the lore of violence-plagued Michoacan state, where gangster exploits in recent years include rolling five human heads onto a dance floor.

The townspeople grasped an essential fact: The talamontes were part of a larger criminal network that controlled drug trafficking and worked hand-in-hand with politicians and police.

“To defend ourselves, we had to change the whole system — out with the political parties, out with City Hall, out with the police and everything,” said Pedro Chavez, a teacher and community leader. “We had to organize our own way of living to survive.”

They decided to target the nexus between crime and politics that has haunted Mexico and do away with the police, the mayor, the political parties.

The town recruited outside legal expertise to exploit provisions of Mexican law that allow communities with indigenous majorities to set up a form of self-government, incorporating traditional “uses and customs” into their rule.

The political parties and their patrons resisted the radical transformation. The case eventually made its way to Mexico’s Supreme Court.

Finally, in 2014 Cheran’s provisional system of self-government was declared legal. The town remains part of Mexico but runs its own show.

On the surface, Cheran seems no different from other places in rural Mexico.

Stands set up in the colonial-era central square hawk foodstuffs, cheap clothing and other items. Each afternoon, residents gather to enjoy an ice cream, sip a juice drink and share gossip and small talk, often about loved ones and neighbors now in the United States.

But something is missing: There is no sign of the political slogans and emblems that are ubiquitous in much of the country.

Electioneering is forbidden inside the town limits, as are political parties. Even motorists entering Cheran are obliged to remove or cover up party bumper stickers.

Residents can cast ballots in state and national elections, but they must do so at special booths set up in nearby towns.

Instead of the traditional mayor and city council, each of the town’s four barrios is governed by its own local assembly, whose members are chosen by consensus from 172 block committees known as fogatas — after the campfires that came to symbolize the 2011 rebellion.

Each assembly also sends three representatives — including at least one woman — to serve on a 12-member town council.

The town receives all the funds — the equivalent of about $2.6 million per year, officials say — that are its due from the state and federal governments. Salaries of 200 or so town employees max out at the equivalent of roughly $450 a month, leaving money to help fund the municipal water system and other services, including a trash recycling program that is a rarity in Mexico.

The armed guards at the town entrances are part of a locally selected police force of 120 or so, known as la ronda comunitaria. No one enters or leaves without inspection.

Cheran was ahead of the curve in the so-called auto defensa movement, which saw many Mexican towns, especially in crime-ridden Michoacan state, set up local militias starting in 2013 as a response to gang-related violence. But other local militias have often turned to the dark side, integrating into existing criminal rings or forming new ones, or have simply disbanded with time. In Cheran, the community police force has stuck and become an integral part of the town’s security.

Without any major crime in Cheran, local officials handle minor offenses such as theft, drunk-driving and disorderly conduct, typically imposing sentences of community service.

Specialized squads also patrol the forests.

“These forests are our essence, they were left to us by our forefathers for protection and nurturing,” said Francisco Huaroco, 41, a member of the forest patrol, as he and a team trekked past stumps that attest to former ransacking. “Without these woods, our community is not whole, is not itself.”

Swaths of bald earth slice through former woods, the scars of looting by the talamontes. Between 2008 and the revolt in April 2011, roughly half of Cheran’s 59,000 acres of forest was illegally felled, authorities said.

“If it had gone on much longer, we would have had nothing left of the forests,” said Roberto Sixtos Ceja.

Sixtos said he left Cheran as a teenager to work in North Carolina — a destination for many here — but returned in 2010 to help the community confront the escalating crisis.

Now 47, he helps manage a vast tree nursery where pine cones are grown into saplings, part of an effort to replenish the hillsides. The nursery holds more than 1 million young trees, of three indigenous pine varieties. The town only allows harvesting of diseased timber or logs downed by storms or other natural causes.

Cheran natives who live in the United States have been closely following events here.

“We never stop being members of this community, people of Cheran,” said Ramiro Romero Ramos, 61, who left almost four decades ago but now heads the Cheran Club of Los Angeles. He recently was visiting to inaugurate a new roof on a primary school playground — a project partially funded by L.A.-area residents from Cheran.

At the Cheran town hall, a multi-hued mural of Emiliano Zapata, the Mexican revolutionary icon, bears the inscription: “Cheran will neither surrender nor be sold!”

Other towns have endeavored to copy Cheran’s transformation, with limited success. The model has relatively little application elsewhere in Mexico, where the vast majority of the population is of mestizo, or mixed-race, origins. Self-rule laws for indigenous communities do not apply.

Not that Cheran doesn’t have its problems, including poverty, lack of opportunity, petty crime.

“But the problems of today don’t compare with what it was like before,” said Estrada, the rebellion organizer. “Now we can go out at night. Before the community felt a great fear: Everyone went inside at 9 o’clock at night and shut their doors.”

With slayings, kidnappings and extortion plaguing areas just outside of Cheran, all here are aware that it would take little for turmoil and conflict to reemerge. The governor of Michoacan has publicly threatened a court case to reverse the town’s system of self-government.

“We in Cheran remain vigilant,” said Juarez Gonzalez, who, six years after her husband’s disappearance, is now a fogata coordinator. “We all know the criminals are close by, and may try to return any time.”

To read the article in Spanish, click here

Twitter: @mcdneville

To read the article in Spanish, click here

Cecilia Sanchez of The Times’ Mexico City bureau and special correspondent Liliana Nieto del Rio in Cheran contributed.

ALSO

Who is spying on Mexico's opposition leaders, journalists and activists?

Venezuelan opposition leader Leopoldo Lopez released from prison and placed under house arrest

How do you prosecute a murder without a body? California has been doing it for more than a century

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.