- Share via

A few months ago, while visiting the rooftop bar at a Residence Inn in Berkeley, I picked up the city’s glossy “official visitors’ guide” and searched it for the historical nuggets that these kinds of publications invariably include.

“For thousands of years before the local arrival of Europeans,” I read, “Berkeley, and the entire East Bay, was the home of the Chochenyo-speaking Ohlone. The specific area of present-day Berkeley was known as Huchiun.”

Not too bad for a public-relations freebie, except it then skipped a few millennia in a speed rush to the appearance of the Spanish in the late 1700s, the discovery of gold (1848), the founding of the University of California in Berkeley (1873) and the free speech movement and Summer of Love in the 1960s, which, according to the guide, endowed the city with “a bias for original thinking” and an “off-beat college town vibe.”

When forces unite with no care for the Constitution, the rule of law or anything you learned in civics class, you can end up with the entrenched overreach of the Plenary Power Doctrine.

I’ve spent most of the last five years digging into California’s past to expose UC’s role on the wrong side of history, in particular Native American history. Beginning in the early 20th century, scholars at Berkeley (and at USC and the Huntington Library) played a central role in shaping the state’s public, cultural identity. They wrote textbooks and popular histories, consulted with journalists and amateur historians, and generated a semiofficial narrative that depicted Indigenous peoples as frozen in time and irresponsible stewards of the land. Their version of California’s story reimagined land grabs and massacres as progress and popularized the fiction that Native people quietly vanished into the premodern past.

Today, prodded by new research and persistent Indigenous organizing, tribal groups and a later generation of historians have worked to set the record straight. For thousands of years, California tribes and the land they lived on thrived, the result of creative adaptation to changing circumstances.

UC Berkeley’s decision to remove Louis Kroeber’s name from its anthropology building was the wrong response to complaints from Native American tribes.

When Spanish and American colonizers conquered the West, tribal groups resisted. In fact, the state was one of the country’s bloodiest regions in the 19th century, deserving of a vocabulary that we usually associate with other countries and other times: pogroms, ethnic cleansing, apartheid, genocide. Despite this devastation, California’s population today includes more than 100 tribes and rancherias.

Very few details from authentic pre-California history filter into our public spaces, our cultural common knowledge. I’ve become a collector of the retrospective fantasies we consume instead — those few sentences in the Berkeley visitors’ guide, Google, whitewashed facts on menus, snippets on maps and in park brochures, what’s engraved on a million wall plaques and enshrined on roadside markers. These are the places where most people encounter historical narratives, and where history acquires the patina of veracity.

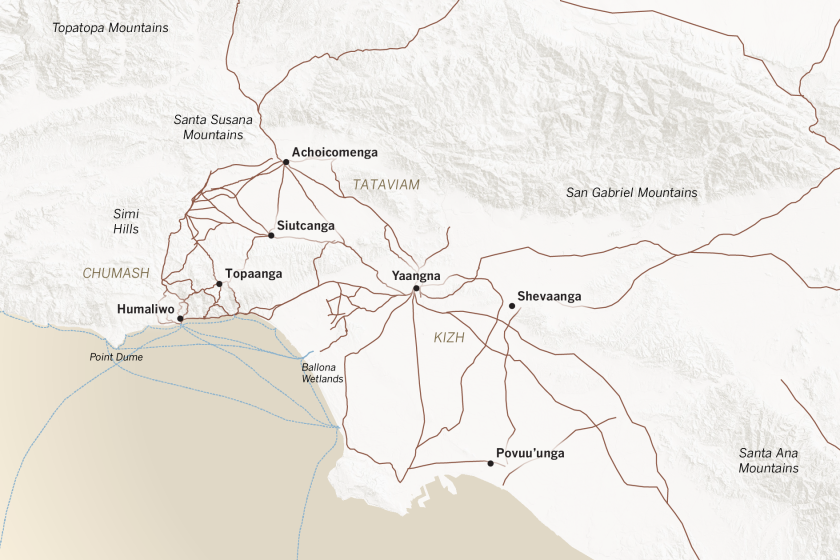

The ‘Mapping Los Angeles Landscape History’ project seeks to illustrate major Los Angeles-area Indigenous settlements.

One Sunday, while waiting for an order of the ethereal lemon-ricotta pancakes at the Oceanside Diner on Fourth Street in Berkeley, I read a bit of history on the menu. The neighborhood, it said, was created in the early 1850s when workers and farmers developed a commercial hub — a grist mill, soap factory, blacksmith and an inn. There was no mention that the restaurant occupied an Ohlone site that flourished for 2,000 to 3,000 years, part of a network of interrelated communities that stretched from the San Francisco Bay, crossing what is now the Berkeley campus, and following a canyon and a fresh-flowing stream into the hills.

A friend who knows I like rye whiskey recently gave me a bottle of Redwood Empire. The wordy label explains that the whiskey is named after “a sparsely populated area” in Northern California characterized by an “often inaccessible coastline drenched in fog, rocky cliffs, and steep mountains” and “home to majestic coastal redwoods.” It’s a place “where you can connect with Nature” but apparently not with the tribes who make it their home now and have done since time immemorial.

Traditional travel guides skip the most troubling information and emphasize California as an exemplar of diversity and prosperity. The bad old days are blamed on Franciscan missionaries who, according to the 1997 Eyewitness Travel Guide for the state, “used natives as cheap labor” and on “European colonists who committed a more serious crime by spreading diseases that would reduce the native population to about 16,000 by 1900.” This shaky history leapfrogs the crimes of Americans and lands in the mid-20th century when Native Americans, they may be surprised to learn, “opted for integration throughout the state.”

The Wilton Rancheria tribe have fought for years to reclaim stolen lands. A 77-acre parcel outside Sacramento is theirs once more.

Guides have become more hip, though they’re still mostly ahistorical. The Wildsam “Field Guide to California,” for example, includes “There There,” by Tommy Orange (Oakland-born, Arapaho and Cheyenne) on its list of must-read fiction, provides a detailed LGBTQ+ chronology, covers Chez Panisse and the Black Panther Party but also reduces Indigenous history to the “1400s [when] diverse native tribes flourish.”

UC Berkeley’s botanical garden, with “one of the largest collections of California native plants in the world,” is located in Strawberry Canyon, the route followed by generations of Ohlone to hunting grounds in the hills. No plaques in the 34-acre park acknowledge the site’s pre-California past and no books in the gift store educate visitors about what contemporary environmentalists are learning from Indigenous land management practices, such as prescribed burns and selective harvesting.

The gaps created by the tendency to present California’s origins sunny-side-up dampen curiosity and contaminate a basic understanding of American history.

Indigenous tribes without federal recognition fiercely opposed a bill that would treat tribes with and without federal recognition differently during land development disputes, prompting the author to pull it.

For example, the Lawrence Hall of Science, a teaching lab for Berkeley students and a public science center, has initiated a project to “promote a clear understanding of the lived experiences of the Ohlone people.” Unfortunately, it dodges the university’s role in systematically plundering Indigenous graves in California and appropriating ancestral burial grounds in Los Alamos, N.M., where UC Berkeley had a role in the creation of the atomic bomb.

Similarly, just about everybody on campus knows the story of the free speech demonstrations, but almost nobody knows about the longest, continuous protest movement in the state, and one still being vigorously waged against the university: the struggle to repatriate ancestral remains and cultural objects that began in the 1900s when the Yokayo Rancheria, according to local media accounts, successfully hired lawyers to stop “grave-robbing operations by [Cal] scientists in the vicinity of Ukiah.”

Even activists in the Bay Area are not immune to this amnesia. In April, I participated in a rally on the Berkeley campus to protest the Trump administration’s devastating attacks on academia. The main speakers, who represented a variety of departments — ethnic studies, African American studies, Latinx studies, Asian American studies and the humanities — defended the importance of anti-racism education and testified to the long history of student protests on the Berkeley campus. What was missing was not only the inclusion of a Native American speaker but also any reference to the ransacking of Indigenous sites that was inseparable from the university’s material and cultural foundations.

I’m reminded of Yurok Tribal Court Chief Judge Abby Abinanti’s admonition: “The hardest mistakes to correct are those that are ingrained.”

Out of history, out of mind.

Tony Platt is a scholar at UC Berkeley’s Center for the Study of Law and Society. He is the author of “Grave Matters: The Controversy over Excavating California’s Buried Indigenous Past” and most recently, “The Scandal of Cal.”

More to Read

Insights

L.A. Times Insights delivers AI-generated analysis on Voices content to offer all points of view. Insights does not appear on any news articles.

Viewpoint

Perspectives

The following AI-generated content is powered by Perplexity. The Los Angeles Times editorial staff does not create or edit the content.

Ideas expressed in the piece

Tony Platt argues that California’s history, particularly regarding Indigenous peoples, is systematically erased from public consciousness through selective storytelling[1]. His key perspectives include:

- Public spaces like visitor guides, menus, and product labels minimize or omit pre-colonial Indigenous history, reducing thousands of years of Ohlone heritage to brief mentions while emphasizing colonial “progress”[1].

- Academic institutions like UC Berkeley historically crafted narratives depicting Native peoples as “vanished” and justified land theft, obscuring atrocities like ethnic cleansing and genocide[2][3].

- Contemporary efforts (e.g., UC Berkeley’s botanical garden, science centers) continue to ignore Indigenous connections to land and the university’s role in plundering graves, despite initiatives claiming to honor Ohlone history[1].

- Even progressive activists and educators overlook Indigenous struggles, such as the century-long fight for repatriation of ancestral remains, focusing instead on more widely recognized social justice movements[1].

- This erasure perpetuates the myth that California’s development was fundamentally benevolent, rather than rooted in violence against its original inhabitants[3][4].

Different views on the topic

Contrasting perspectives emphasize practical limitations and differing priorities in historical representation:

- Public-facing materials (travel guides, menus) prioritize brevity and tourism appeal; comprehensive historical context is impractical for casual consumption and could deter engagement with California’s cultural offerings[1].

- Universities like UC Berkeley contribute significantly to historical reckoning through contemporary research and programs, rendering Platt’s criticism of past academic practices less relevant to current institutional missions[3][4].

- Resource constraints necessitate selectivity in memorialization; focusing on universally resonant narratives (e.g., Free Speech Movement) ensures broader public impact than niche historical grievances[1].

- Corporations (e.g., Redwood Empire whiskey) emphasize natural aesthetics over human history to create marketable brand identities; invoking Indigenous connections could be seen as exploitative if not authentically led by tribes[1].

- Past injustices, while acknowledged, are considered resolved through modern legal frameworks and reparations; continual focus on historical crimes distracts from present-day solutions for Native communities[3].

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.