Migrants in U.S.-bound caravan break through fence at Guatemala-Mexico border

Central Americans traveling in a mass caravan toward the United States crossed into Mexico by jumping from a bridge on the Guatemalan border and swimming to the Mexican side or climbing aboard makeshift rafts, which ferried them to shore.

- Share via

Reporting from Ciudad Hidalgo, mexico — Thousands of Central Americans in a U.S.-bound migrant caravan began pushing their way from Guatemala into Mexico on Friday, pulling down border fences and storming toward the Mexican immigration post.

“One way or another, we will pass!” the migrants chanted as they approached the gates in the Guatemalan town of Tecun Uman.

The migrants rushed past Guatemalan soldiers onto a bridge that crosses the muddy Suchiate River, which separates the two countries.

But Mexican police in riot gear, at one point using tear gas to keep the crowd at bay, appeared to have stopped the group, which originated in Honduras last week, from bypassing immigration controls and illegally advancing further into Mexican territory.

The caravan of more than 2,000 people — men and women, teenagers and infants — on foot and in vehicles has become politically explosive. President Trump has made it an issue in the midterm election and threatened to cut aid to Central American nations, close the U.S.-Mexico border and deploy troops there if Mexico failed to stop the migrants.

At a campaign stop in Arizona on Friday, Trump expressed gratitude to Mexican officials for their efforts to deter the caravan. “It’s being stopped as of this moment by Mexico. So we appreciate very much what Mexico is doing,” he told reporters in Scottsdale. “As of this moment, I thank Mexico. I hope they continue.”

As they neared the Mexican side of the bridge, the migrants clashed with Mexican authorities, and several people were injured — including migrants, police and at least one Mexican journalist.

While a Mexican federal police helicopter hovered overhead, hundreds of migrants remained massed on the bridge, demanding that they be allowed to cross.

Migrants gathered outside the Mexican immigration headquarters shouted “Ayuda!” for help, as some women in the group appeared to be fainting in the sweltering heat.

The Mexican government brought a large bus to the crossing, and a small number of migrants, mostly women and children, were allowed to board. It appears they were to be processed for refugee status or other potential protections.

Mexican authorities, who have also sought help from the United Nations, said each migrant would be subjected to immigration inspection and that those lacking legal papers to be in Mexico would be detained and deported. Those seeking asylum would be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

Many shops here in Ciudad Hidalgo, on the Mexican side of the border, were closed because of fears of violence and looting. But residents of the town lined up to watch the spectacle.

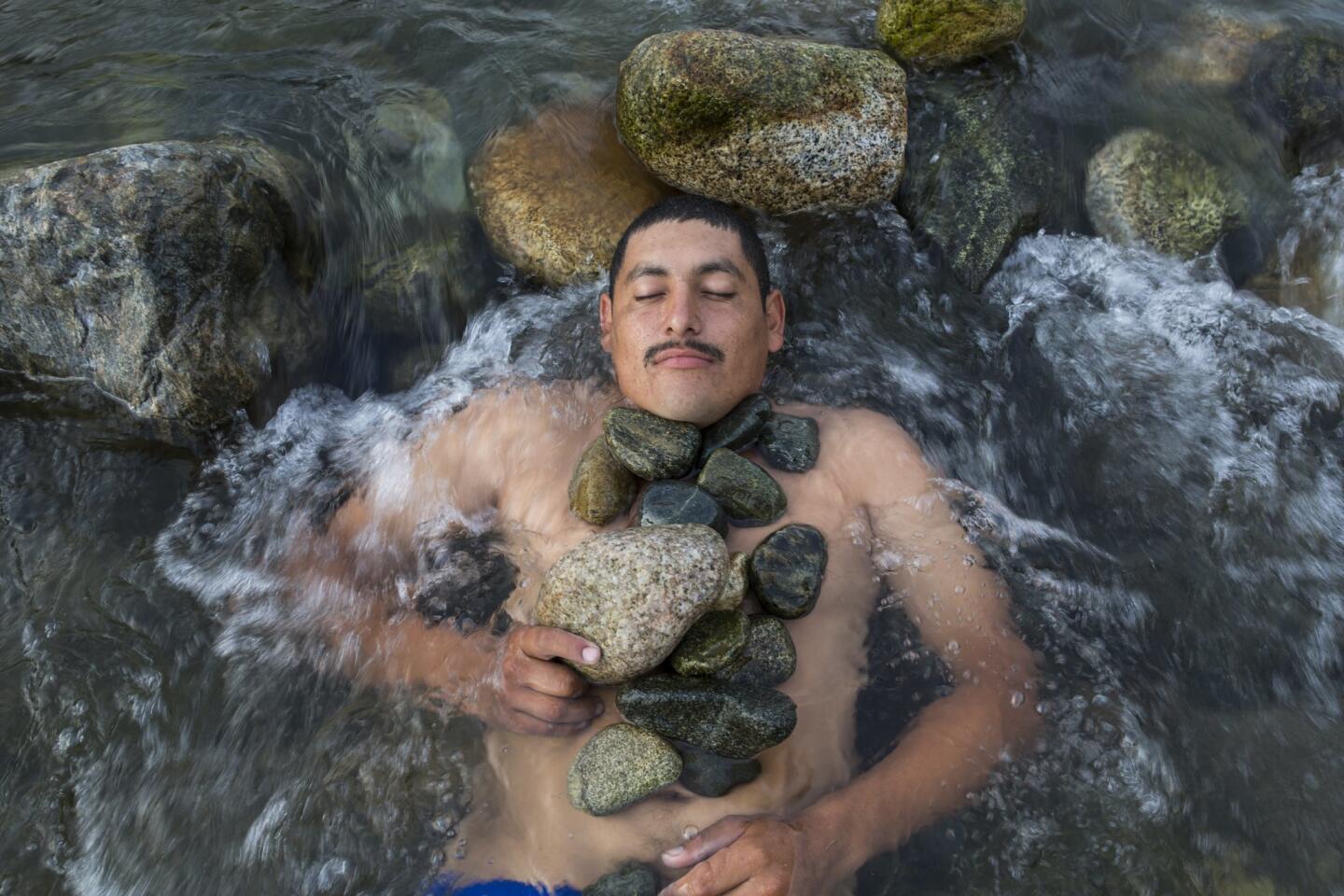

As the day wore on, migrants began jumping from the bridge and swimming to the Mexican side or climbing aboard makeshift rafts, which ferried them to shore.

Darling Mejia, 20, had been waiting on the bridge for two hours before he began to worry that he might suffocate and decided to jump. He emerged on the shore shaking and dripping wet, his red shirt hanging off his thin figure.

“You have to understand,” he said. “All we want is a better life.”

It was the kind of chaotic scene that Mexican authorities had hoped to avoid.

In recent days, as the much-publicized caravan traversed Guatemala, Mexico dispatched planeloads of federal police and other authorities in anticipation of an influx.

Most of the migrants are citizens of Honduras, and many waved its blue-and-white national flag.

It was not immediately clear how many had entered Mexico.

One who made it in was 19-year-old Mario Leon, who abandoned the caravan after a week and crossed Thursday in a raft.

He left Honduras, he said, because he had no choice. “There’s no work. There’s no money,” he said. “The work there pays just three dollars a day. How can I make a life?”

Now Leon was waiting for two of his aunts who he said were stuck on the bridge. Waving a Honduran flag to cheer on the migrants, he didn’t seem particularly worried about Mexican immigration authorities.

Stopping illegal immigration and erecting a wall along the border with Mexico have been hallmark promises of Trump since he was a presidential candidate.

Late Thursday, Trump retweeted an image of reinforcements arriving at Mexico’s southern border and wrote: “Thank you Mexico, we look forward to working with you!”

For Mexico, the caravan had posed a major dilemma, pitting compassion for the migrants and respect for human rights against the country’s relationship with the United States.

Mexican authorities have vowed to respect the human rights of the migrants but said those lacking legal authorization to cross into Mexico would be detained.

“The essence of our position is the respect of the human rights and dignity of the people, and the protection of this migrant group, particularly the most vulnerable,” Mexico’s foreign secretary, Luis Videgaray, said Friday at a meeting in Mexico City with U.S. Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo.

Pompeo said the situation was reaching “a moment of crisis.”

Mexico’s interior secretary, Alfonso Navarrete Prida, denounced violence and acts of “provocation” by some of the migrants in the caravan and vowed that Mexico would respect the rights of those seeking entry into Mexico.

Some in the caravan had broken an accord with Mexican authorities to proceed in an orderly fashion at the border, Navarette said.

Mexico has long been the major route for Central Americans seeking to make it to the United States. Organized groups of smugglers assist the migrants on their way north, charging $5,000 or more a person.

In recent years, Mexican authorities have stepped up efforts to stop Central Americans from illegally entering the country, and set up checkpoints to catch those who get past the border.

Between January and August, Mexican authorities deported 69,929 Central Americans, an almost 40% increase compared with the same period during 2017.

Linthicum reported from Ciudad Hidalgo and McDonnell from Mexico City. Cecilia Sanchez of The Times’ Mexico City bureau and Times staff writers Tracy Wilkinson in Washington contributed to this report.

UPDATES:

4:10 p.m.: This article has been updated throughout with staff reporting.

12:25 p.m.: This article was updated with additional reporting on the gate being taken down.

This article was originally published at noon.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.