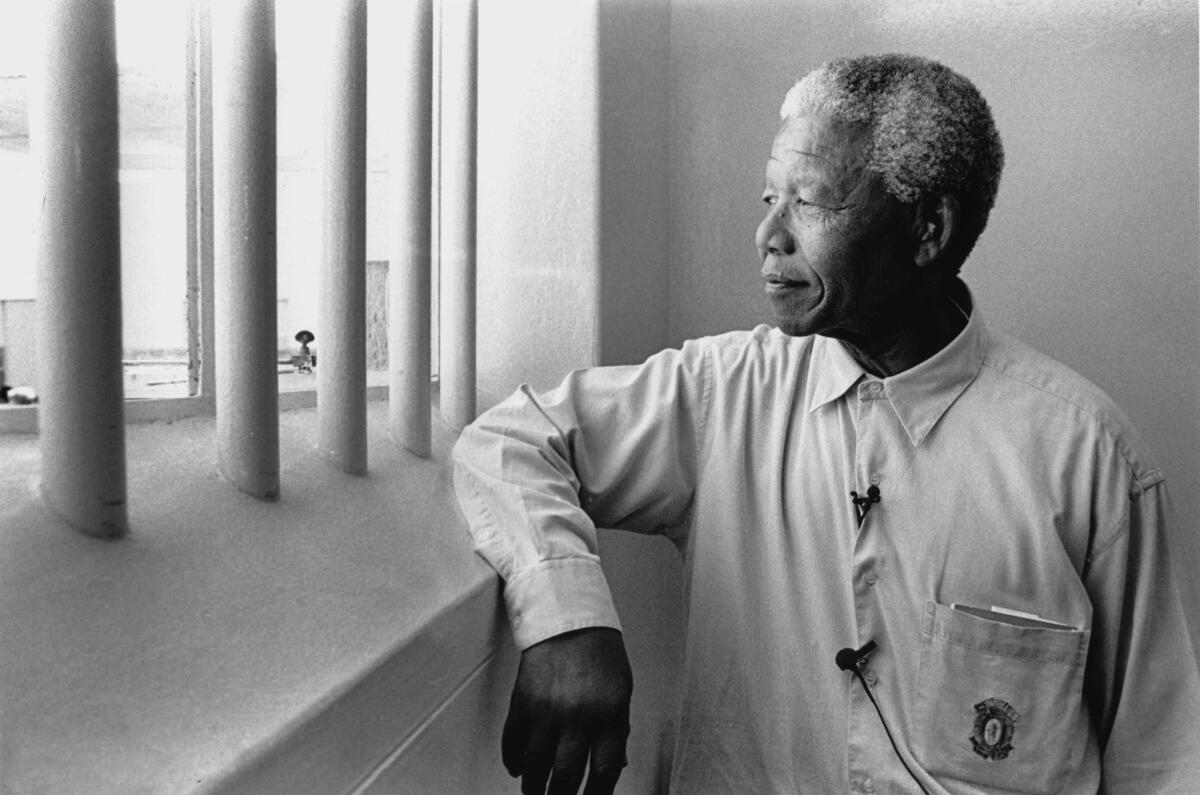

Robben Island: The place that changed Nelson Mandela

- Share via

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa — The brightly painted ferry sailed to the island prison like a dazzling bird swooping down to land. The prisoner caught sight of the vessel, far off on the shimmering sea.

The boat was his friend. It was bringing his family to see him.

It was Nov. 9, 1970, and the prisoner was Nelson Mandela, held on Robben Island for his leading role in planning bomb attacks.

“A visit to a prison has a significance difficult to put into words,” Mandela wrote in a letter to a friend in 1987. These were the “unforgettable occasions when that frustrating monotony is broken and the entire world is literally ushered into the cell.”

PHOTOS: Nelson Mandela through the years

Later that afternoon, watching the ferry steam away with his wife, who looked frail, Mandela felt desolate. The boat was no longer his friend, but his enemy.

“Though it still retained its brightness, the beauty I had seen only a few hours before was gone. Now it looked grotesque and quite unfriendly. As it drifted slowly away with you, I felt all alone in the world,” he wrote in a November 1970 letter to his wife, Winnie Mandela.

Mandela’s cell was small and bare with a lidded metal bucket for a toilet, a narrow bed, a small table and three small painted metal cupboards fixed high on the wall. Outside, tall stone towers glared with slitted windows like ever-watching eyes.

The prisoners emptied their own buckets each morning. Mandela emptied his and that of a neighboring prisoner who left his cell for his daily labor. The job had fallen to another prisoner, who refused.

“So then I cleaned it for him because it meant nothing for me. I cleaned my bucket every day and I had no problem, you see, in cleaning the bucket of another,” he says in his book “Conversations With Myself.”

FULL COVERAGE: Anti-apartheid icon Nelson Mandela dies

On Robben Island, the political prisoners faced hard labor, breaking rocks in the lime quarry. They were ordered not to sing, and were denied reading material and the opportunity to play sports.

“They wanted to break our spirits. So what we did was sing freedom songs and everybody … went through the work with high morale and then of course dancing to the music as we were working, you know. Then the authorities realized that … ‘these chaps are too militant. They’re in high spirits.’ And they say, ‘No singing as you are working.’ So you really felt the toughness of the work.”

Charges were trumped up by the wardens and punishments ensued: solitary confinement and withholding of food.

“What happened was that they would decide in the morning before we [went] to work that so-and-so and so-and-so would be punished. And once they took that decision, it didn’t matter how hard you worked that morning. You would be punished at the end of the day.”

PHOTOS: The world reacts to Nelson Mandela’s death

One of the wardens would urinate next to the prisoners, sometimes right by the table where their food was dished out.

But the apartheid regime made a mistake: keeping the political prisoners together, allowing the leaders of the banned African National Congress and other resistance groups to mix. Politics went on inside the prison. Mandela penned an autobiography, letters to lawyers and other political statements, all of which were smuggled out.

In addition to politics, there was education. Robben Island was later known to the liberation struggle veterans as “Mandela University.” Between their laboring in the quarry, prisoners gave one another lessons. The current South African president, Jacob Zuma, was taught to read and write on Robben Island. Mandela completed a law degree.

The ANC leadership used the daily injustices in the prison as another platform for its struggle against oppression of blacks.

For Mandela and the other prisoners, the routine was hard to bear.

“Every day is for all practical purposes like the day before: the same surroundings, same faces, same dialogue, same odor, walls rising to the skies and the ever-present feeling that outside the prison gates there is an exciting world to which you have no access,” Mandela wrote in the 1987 letter. Toward the end of his 27 years in prison, most of them on Robben Island, some wondered whether Mandela would be out of touch when he was released.

“Businesspeople and Western officials fretted that he would be a Rip Van Winkle figure, clinging to the outdated economic philosophy he had espoused before being imprisoned,” Alec Russell wrote in the book “After Mandela.” “Some nervously remembered that as a politician he had a reputation for being a hothead.”

He had gone into prison an angry rebel who believed that violent revolution was the only answer. After his release, the firebrand rhetoric was gone (to the disappointment of some). Rather than the stirring oratory of yesteryear, his speeches were calm and pacifying, always calling for reconciliation and unity.

At the negotiating table, he persuaded whites to surrender power. He averted a tribal and civil war that many felt certain was inevitable, and managed to unite South Africans under his banner of nonracial democracy.

Mandela never forgot the good prison guards and police, or the bad. Years later, he and fellow prisoner Ahmed Kathrada discussed the idea of inviting wardens and some members of the apartheid security police over for lunch. They even talked of inviting one of the worst, who’d severely tortured some ANC activists before they went to prison.

Robben Island left him damaged. But without the years of self-examination and meditation — seeing positive things in his darkest hours — Mandela might never have become such a remarkable leader after he walked free.

“At least, if for nothing else,” he wrote in a 1975 letter to his wife, “the cell gives you the opportunity to look daily into your entire conduct, to overcome the bad and develop whatever is good in you.

“Never forget that a saint is a sinner who keeps on trying.”

ALSO:

The words of Nelson Mandela echo through the decades

The brave, the powerful, the liberated remember Nelson Mandela

Nelson Mandela’s legacy: As a leader, he was willing to use violence

Twitter: @robyndixon

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.