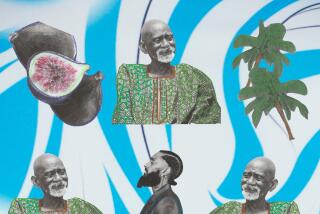

Those Clinging to Old Ways Come to Him for Cures : Seminole Medicine Man Still Active at 84

- Share via

BRIGHTON RESERVATION, Fla. — Frank Shore slowly leans back into a well-worn sofa in his cement-block house and shuts his eyes as he seemingly goes back in time.

After a pause, he says with eyes still closed: “In the old days, it was just Indian medicine when the Indian lived alone. Now, Indians take white man’s medicine.”

Shore, at 84, has been a Seminole medicine man for almost 60 years. He continues to care for older residents among the 355 Indians living on this 45,000-acre reservation isolated on the northwest corner of Lake Okeechobee.

Those who come to him for his special herbs and cures adhere to the “old ways” or believe that modern medicine administered at the reservation’s health clinic cannot cure all health problems.

He learned his profession from an uncle, Billie Smith, who, he says, taught him nature’s secrets. It took seven years of apprenticeship to learn how to convert grasses, roots, leaves and myriad ingredients into salves, ointments and remedies. Hundreds of ceremonial songs and chants are needed for the process of making Indian medicine, he added.

Medicine men not only treat aches, pains and illnesses, but also provide potions to resolve bad dreams and unrequited love. There are also medicine women in the Seminole tribe who help with female ailments, childbirth and personal problems that women may have.

Held at Secret Site

Medicine men and women have little authority in tribal government. However, it is the medicine man who reigns during the Green Corn Dance, a four-night ceremony similar to Thanksgiving.

It is a time when the Seminoles reacquaint themselves with their heritage.

The annual celebration occurs in early summer and is a joyous occasion filled with folklore, storytelling and dancing. The tribe congregates at a secret site chosen by the medicine man and outsiders are rarely permitted.

No modern conveniences are used during the Green Corn Dance. The participants live in open-sided, thatch-roofed chickees, cook by open fire and wear traditional clothing.

Although this reservation, one of four in Florida, has limited contact with white people, Shore is gradually losing touch with his own people because of a language barrier. He speaks Creek with his wife, Lottie, family members and those who were taught the language of their ancestors, while most of the residents use English.

Some also speak the language of the Miccosukees, another linguistic group of the Seminoles who have their reservation on Tamiami Trail southwest of Miami.

“The Indian children don’t speak Creek anymore,” Shore laments. “They learn English first.” Partly because of the language barrier with the younger Seminole generation, Shore has no one to whom to pass on his knowledge.

“If someone would ask me, I’d teach them,” he said through an interpreter.

Shore remembers hardships that Indians once suffered because of discrimination and the scarcity of decent jobs, but he shows no bitterness.

“Some whites didn’t care too much for Indians, but some were friendly.

“The white man is interested in the Seminole ways and is getting information from the older ones and putting it on paper,” he said. “The Indians aren’t doing it.”

Seldom Watches TV

Shore lives quietly with his wife and a married daughter, one of seven children the couple have. His favorite foods are fried fish and lemon pie. He seldom watches the black-and-white portable television in the house. “Too much talking,” he explains.

Old friends like Frank Cypress still come by. Cypress will bring a jug filled with herbs for Shore to turn into medicine and the two will spend hours telling tales and singing songs.

Despite arthritis in his feet and failing eyesight, Shore still finds humor in life.

When Lottie recalls that she has been married to Shore since 1937, Shore responds with a laugh: “It seems longer than that.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.