- Share via

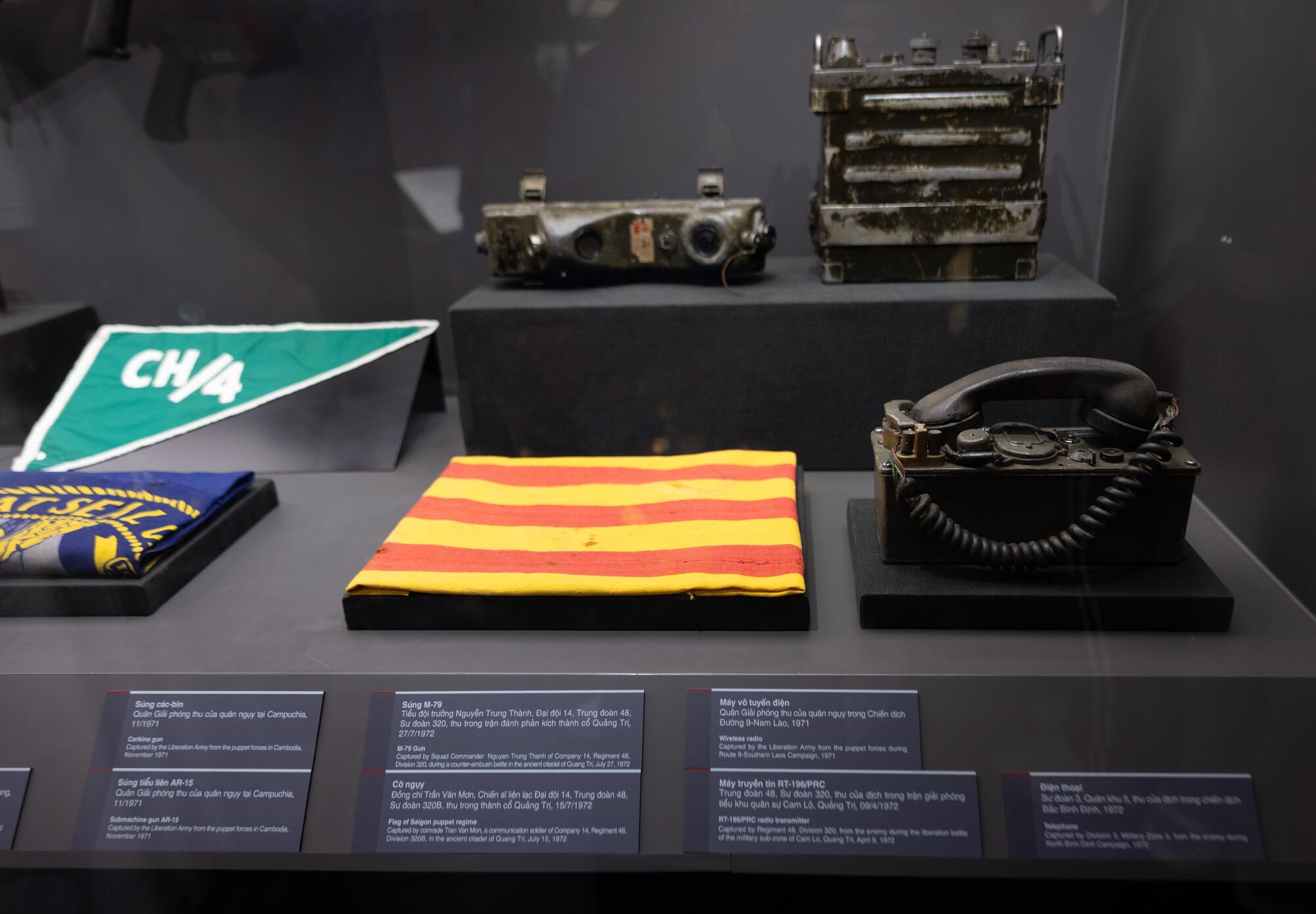

HANOI, Vietnam — Last fall, Vietnam opened a sprawling new military museum here, and among thousands of artifacts in the four-story building and a courtyard filled with tanks and aircrafts, one exhibit quickly became the star attraction: the flag of South Vietnam.

The government regards the yellow banner with three red stripes as a sign of resistance to the communist regime, violating laws about inciting dissent. With few exceptions, it is not displayed.

Reactions to the rare sighting soon went viral. Young visitors at the Vietnam Military History Museum posted photos of themselves next to the flag with deep frowns, thumbs down or middle fingers raised. As the photos drew unwanted attention, the flag was unpinned from a wall and folded within a display case. Social media content featuring rude hand gestures was scrubbed from the internet.

But the phenomenon persisted.

Several weeks ago, schoolchildren who were on tour made it a point to check out the flag. Every few minutes, a new group crowded around the banner — also known online as the “Cali” flag — holding up middle fingers or crossing their hands to form an “X.”

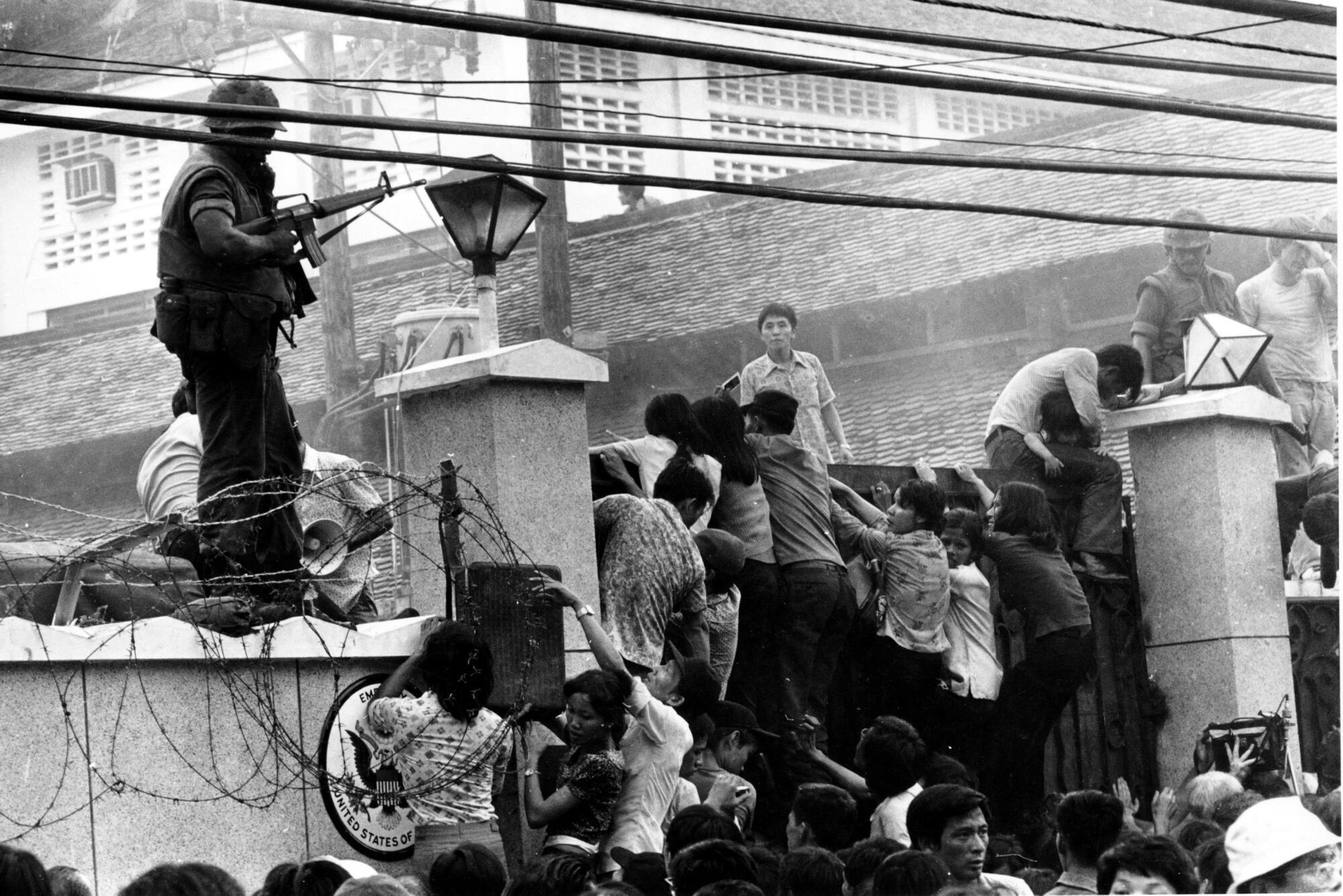

In Vietnam, Cali — sometimes written as “kali” — has long been a reference to the Vietnamese diaspora in California, where many Vietnamese-Americans still fly the flag of the south to represent the fight against communism and the nation they lost with the war.

People who live in Vietnam, however, are more likely to view it as a symbol of American imperialism, and as nationalistic sentiment here has swelled in recent years, evoking the Golden State has become a shorthand of sorts to criticize those opponents.

“They use that as a label against anyone who disagrees with state policy,” says Nguyen Khac Giang, a research fellow at Singapore’s Yusof Ishak Institute, known for its political and socioeconomic research on Southeast Asia.

There have been other signs of growing nationalism in the past year, often in response to perceptions of American influence. In addition to animosity toward the “Cali” flag, a U.S.-backed university in Ho Chi Minh City was attacked over suspicions of foreign interference. And an aspiring Vietnamese pop star who’d been a contestant on “American Idol” was savaged on social media last summer after footage of her singing at the U.S. memorial service of an anti-communist activist surfaced.

Vietnamese nationalism, Giang said, is bolstered at every level by the country’s one-party rule.

The government controls education and public media; independent journalists and bloggers who have criticized the government have been imprisoned. In addition, the party’s ability to influence social media narratives has improved over the last several years, particularly among the nation’s youth.

Since 2017, Vietnamese authorities have employed thousands of cyber troops to police content online, forming a military unit under the defense ministry known as Force 47. In 2018, the country passed a cybersecurity law that enabled it to demand social media platforms take down any content that it deems anti-state. The resulting one-sided discourse means that views that don’t align with official propaganda often draw harassment and ostracism.

At times, the government has also used that power to try and rein in nationalism when it grows too extreme — though banning posts about the South Vietnam flag did little to quell enthusiasm at the museum.

Some visitors who were making hand signs said they were expressing their disapproval of a regime that, they’d been taught, oppressed Vietnamese people. One teenager unfurled and held up the national flag — red with a yellow star — for a photo.

“It’s hard to say if I agree or disagree with the rude gestures,” said Dang Thi Bich Hanh, a 25-year-old coffee shop manager who was among the visitors. “Those young people’s gestures were not quite right, but I think they reflect their feelings when looking at the flag and thinking about that part of history and what previous generations had to endure.”

Before she left, she took a selfie with her middle finger raised to the folded cloth.

:::

Five years ago, when a student from a rural region of the Mekong Delta earned a full scholarship to an international university in Ho Chi Minh City, it seemed like a dream come true. But last August, when the school was caught up in the growing wave of nationalism, he began to worry that his association with Fulbright University Vietnam could affect his safety and his future.

“I was scared,” said the recent graduate, who requested anonymity for fear of retribution. He had just started a new job in education and avoided mentioning his alma mater to coworkers and wearing shirts marked with the school name.

“You had all kinds of narratives. Especially with the disinformation spreading at the time, it had some negative impacts on my mental health.”

The attacks included allegations that Fulbright, which opened in 2016 with partial funding from the U.S. government, was cultivating Western liberal and democratic values that could undermine the Vietnamese government.

Nationalists criticized any possible hint of anti-communist leanings at the school, such as not prominently displaying the Vietnamese flag at commencement. Even last year’s graduation slogan, “Fearless,” sparked suspicions that students could be plotting a political movement.

“You are seeing new heights of nationalism for sure, and it’s hard to measure,” said Vu Minh Hoang, a diplomatic historian and professor at the university.

Hoang said the online allegations — none of which were true — led to threats of violence against the university, and there was talk that some parents withdrew their children because of them. Several students said their affiliation drew hate speech from strangers and distrustful questions from family members and employers.

Academics said the Vietnamese government likely acted quickly to shut down the backlash against Fulbright in order to prevent the anti-American sentiment from harming its ties with the U.S., its largest trade partner. But some of the original accusations were propagated by state media and bots associated with the Ministry of Defense, hinting at a schism within the party.

Hoang said that while nationalism is often utilized as a uniting force in Vietnam and beyond, it also has the potential to create instability if it grows beyond the government’s estimation or control. “For a long time, it has been the official policy to make peace with the overseas Vietnamese community and the United States,” Hoang said. “So this wave of online ultranationalism is seen by the Vietnamese state as unhelpful, inaccurate and, to some extent, going against official directions.”

:::

Last summer, footage of Myra Tran singing at the Westminster funeral of Ly Tong, an anti-communist activist, surfaced online. She’d achieved a degree of fame by winning a singing reality show in Vietnam and appearing on “American Idol” in 2019, but she received harsh condemnation from online nationalists and state media when the video from several years ago went viral.

Facebook and TikTok users labeled Tran, now 25, as traitorous, anti-Vietnam — and Cali.

The controversy prompted a more broadly-based movement to ferret out other Vietnamese celebrities suspected of conspiring against the country. Internet sleuths scoured the web for anyone who, like Tran, had appeared alongside the flag of South Vietnam and attacked them.

An entertainment writer in Ho Chi Minh City, who did not want to be identified for fear of being targeted, says that as Vietnamese youth have become more nationalistic online, musicians and other artists have felt pressure to actively demonstrate their patriotism or risk the wrath of cancel culture.

He added that the scrutiny of symbols like the South Vietnam flag has given those with connections to the U.S. greater reason to worry about being attacked online or losing job opportunities. That could discourage Vietnamese who live overseas — a demographic that the government has long sought to attract back to the country — from pursuing business or careers in Vietnam.

“There used to be a time when artists were very chill and careless, even though they know there has been this rivalry and this history,” he said. “I think everybody is getting more sensitive now. Everyone is nervous and trying to be more careful.”

Tran was bullied online and cut from a music television program for her “transgression.” She issued a public apology in which she expressed gratitude to be Vietnamese, denied any intention of harming national security and promised to learn from her mistakes.

Two months later, Tran was allowed to perform again. She returned to the stage at a concert in Ho Chi Minh City, where she cried and thanked fans for forgiving her.

But not everyone was willing to excuse her. From the crowd, several viewers jeered and yelled at Tran to “go home.” Videos of the concert sparked fierce debate on Facebook among Tran’s defenders and her critics.

“The patriotic youth are so chaotic now,” one Vietnamese user complained after denouncing the hate that Tran was receiving online.

Another shot back: “Then go back to Cali.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.