Vaccine Found to Prevent Herpes in Lab Animals; ‘First Step’ to Human Antidote

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Animal studies have demonstrated for the first time that a genetically engineered herpes vaccine can prevent both initial and later outbreaks of the disease, “the first step toward developing a vaccine at the human level,” researchers at the National Institutes of Health announced Thursday.

Studies on mice show that the vaccine, unlike others being tested, protects against the development of “latency”--the potential for subsequent infections--for some weeks or months after initial exposure to the herpes virus, said Dr. Abner L. Notkins, lead scientist on the project.

Human Vaccine Long Way Off

However, Notkins emphasized in an interview that, even if the experiments continued to prove successful, a human vaccine is still as long as four or five years away. The vaccine, if it is developed, will be valuable only in protecting those persons who have never contracted herpes and is expected to have no effect on those who already have the disease.

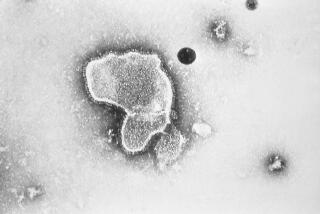

Herpes simplex II, one of several types of the herpes virus, is the strain responsible for genital herpes, the incurable, sexually transmitted disease that may already afflict as many as 20 million Americans and results in an estimated 200,000 to 300,000 new cases each year. With genital herpes, the virus invades the nerves and continues to live in the ganglia, or nerve endings, often producing subsequent outbreaks of infection.

“If a vaccine is going to be effective in (treating) human herpes, it has to prevent the development of this latent infection,” said Notkins, chief of the oral medicine laboratory of the National Institute of Dental Research. “Once the virus gets into the nerves, that’s it. It’s all over. We have to prevent it from getting into the nerves.”

Results ‘Very Promising’

He called the preliminary results “very promising” but said that more research is needed.

“We still have to determine the duration of immunity,” said Notkins, who conducted the work with Dr. Bernard Moss of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. “We know it lasts several months, but we don’t know yet if it lasts much longer than that. Only when we get the answer will we be able to make a decision about going on to human studies.”

The National Institutes of Health scientists used genetic engineering techniques to insert a gene from the herpes virus into another virus, called vaccinia, or cowpox, which is the basis of the smallpox vaccine. The combined vaccine was then injected into hundreds of mice and produced high levels of neutralizing antibodies, substances carried in the bloodstream that fight disease.

The researchers said that the experimental vaccine gave the mice initial protection against two kinds of herpes viruses--herpes simplex I, which causes human cold sores, and herpes simplex II. More important, Notkins said, subsequent experiments exposing immunized mice to additional doses of herpes virus showed that about two-thirds of the animals were also protected from developing a latent infection, even though they were given “fairly high” doses of herpes virus.

Raises Antibodies in Animals

“This vaccine will raise neutralizing antibodies in animals,” Notkins said. “It will protect animals from a lethal challenge, and it will prevent the majority of the animals from developing a latent infection.”

He said that further work is needed to determine why the antibodies failed to work in the one-third of the mice who developed latent infections.

In January, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first pill to treat and prevent outbreaks of genital herpes. The pill, sold under the name Zovirax, is not a cure for the disease but can provide effective, long-term relief from symptoms and significantly reduce the chance of spreading the virus.