Argentine Army Parades for 1st Time Since Falklands

- Share via

BUENOS AIRES — Beleaguered and resentful, the Argentine armed forces Tuesday paraded through the streets of Buenos Aires for the first time since losing a war, a government and public confidence.

On a bright winter’s day, 2,500 troops marched through the historic Plaza de Mayo in an Independence Day celebration. They saluted elected President Raul Alfonsin, who has vowed to strengthen civilian control over a military establishment that has long been the decisive arbiter of Argentine political life.

With units ranging from a squadron of jet fighters to a ceremonial cavalry regiment in colonial uniform, the military parade was the Argentine capital’s first since the disastrous 1982 Falkland Islands War. Loss of the war with Britain speeded the end of military government--a process that began in 1976 and ended with Alfonsin’s election in 1983.

Smaller Crowds

Crowds were smaller than at past parades commemorating Argentina’s 1816 independence from Spain. However, the overall public reaction was positive, both to Alfonsin and to marching units drawn principally from military academies.

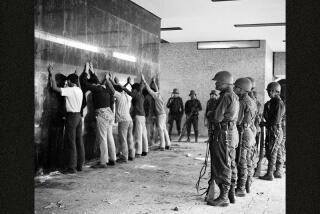

About 100 people who tried to call attention to those who disappeared during the military’s “dirty war” against terrorism in the 1970s were barred from the plaza by riot police. The demonstrators carried a banner that read: “We Demand Justice for the 30,000 Desaparecidos and Trial for the Guilty.”

Right-wing youths crossed police lines several times to scuffle briefly with the human rights activists.

The ceremonial reappearance of the armed forces in the capital’s streets amounted to a successful test of public reaction. Anti-military sentiments, which ran high after the 1982 defeat, have been stoked by the trial of nine former junta members alleged to have been involved in the “dirty war,” including three generals who ruled Argentina from 1976 to 1983.

Alfonsin, who personally ordered the trial, calls for a reconciliation between the people and the armed forces, but at the same time he insists that the armed forces accept civilian control.

Reform Urged

In a tough speech at an annual military banquet last week, Alfonsin called for “true military reform” in which the armed forces “will acquire new moral tone within the framework of absolute respect for institutional order.”

Scoring Argentina’s history in the last half century of repeated military coups supported by civilian politicians, Alfonsin urged the armed forces to stick to their constitutional task of defending against foreign threats.

“In recent years, vast sectors of Argentine society fell into the tragic error of believing that by sacrificing democracy they were creating better conditions to fight terrorism,” Alfonsin said. “Instead, terrorism simply changed its colors. Cruelty grew to include violence and contempt for human life--the very things which were supposed to be under attack.”

Alfonsin’s audience of military leaders heard the 45-minute address stony-faced. There was no applause.

“It is difficult to believe that a civilian president would dare speak of military reform. Or, that he would treat the military as his subordinates,” wrote Argentine newspaper editor Jacobo Timerman after the speech. “For the first time in modern Argentine history, a president has said military leaders of the last half century did not comply with their duty.”

Key Officers Fired

Armed forces resistance to greater civilian supervision and to austerity budgets--part of an overall attack on government waste--has led to the dismissal of some key officers and the resignation of others.

There is a particular and ill-concealed military hostility to the trial in which the former commanders are accused of masterminding state terrorism to combat Marxist guerrillas between 1976 and the end of 1980.

By documented count of a blue ribbon government commission, 9,000 people--the “desaparecidos”--are still missing. Human rights groups say the true number is much higher.

The armed forces deride the trial--”a Roman circus” one retired general called it. Officers say the guerrillas started the so-called dirty war and that the only way to defeat them was by fighting fire with fire. By military count, the guerrillas killed 531 armed forces and police personnel and 118 civilians between 1970 and 1980.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.