He Keeps Predicting, Come Hail, High Water : Forecasts Weather Years in Advance

- Share via

World War II might have been different without Irving Krick.

The 1960 Winter Olympics could have flopped.

Even a party thrown Sept. 29 by Lady Bird Johnson was scheduled only after calling on this silver-haired consultant’s expertise.

Because, at 78, after five decades of forecasting the future, Irving Krick is not your average weatherman.

Using a controversial method he developed in the 1940s, Krick claims to be the only meteorologist--inside or outside of government--capable of making reliable long-range weather predictions for dates years in advance. Krick says that, after being consulted, he accurately forecast the weather for the D-Day invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, the VIII Winter Olympics at Squaw Valley, Calif., and Lady Bird Johnson’s picnic for the National Wildflower Research Center in Middleburg, Va., last month.

By studying records of past weather patterns dating to the turn of the century, rather than waiting for weather to show up on satellite pictures, Krick claims that he can consistently make such predictions with an accuracy rate of up to 90%.

Rarely Accurate

More conventional forecasters believe that long-range predictions, if possible at all, rarely are accurate.

Described by friends as a pioneer and by foes as a quack, Krick has made a $1-million-a-year business of providing prognoses for industry, agriculture, the armed forces and celebrities. His firm, Irving Krick Associates Inc., employs four meteorologists in Palm Springs, but Krick operates mostly out of his Pasadena home, where he maintains close ties with Caltech and Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

A tall man with large, imposing features, Krick has not let age slow his work. His manner is feisty and gregarious, traits which friends say make him appear eccentric and unorthodox to the scientific community.

“Weather is my life,” Krick said. “If I retired, I’d be dead the next day.”

His clients, who come from 33 states and 14 foreign countries, have ranged from Walt Disney to the Mexican Department of Agriculture to the old Brooklyn Dodgers to the inaugural committees of every U.S. President from Dwight D. Eisenhower to Jimmy Carter.

“A lot of people swear by the Farmer’s Almanac,” said Bess Abell, social secretary for the Administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson and organizer of the picnic sponsored by Johnson’s widow.

“I swear by Dr. Krick.”

Success Where Others Fail

And whether he is predicting the weather for a wedding date or projecting rainy seasons for a hydroelectric company, Krick appears to succeed where other forecasters falter.

The National Weather Service, for example, publishes a winter forecast every year at the end of November, but a spokesman for the government agency said that the seasonal prediction is only a little better than 50% accurate.

“You could do almost better flipping a coin,” said Jack LaCovey, a spokesman for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Rockville, Md., which oversees the National Weather Service.

Weather Services Corp. in Bedford, Mass., which claims to be the nation’s largest forecasting business, does not charge its clients for extended forecasts. “When you start talking beyond 10 days, you enter the stage of speculation,” said Dave Taylor, chief climatologist. “It’s totally beyond the state-of-the-art.”

Although Krick is reluctant to share the secrets of his craft, he says his predictions are based on atmospheric rhythms influenced by a combination of “terrestrial and extraterrestrial forces.” Most forecasters base their predictions on current weather activity, but Krick has been able to discover historical weather patterns that he says are unknown to other meteorologists.

“We’ve maintained a position at least a generation ahead of our peers,” Krick said.

Years in Advance

While forecasts from most of the other 97 weather firms in the country are reliable only for a few days, Krick said, his clients pay fees ranging from $100 to $100,000 for accurate predictions made weeks, months and often years in advance.

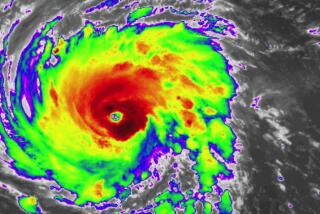

Dow Chemical Co. uses Krick’s forecasts to determine when it should be prepared for hurricanes at its Freeport, Tex., plant.

Farmer-Stockman Magazines, an agricultural journal serving Oklahoma and Texas, has been publishing Krick’s monthly forecasts for 40 years.

“The Weather Bureau couldn’t give us what we needed,” said Ferdie Deering, former editor of the magazines, who added that Krick has been about 75% to 85% accurate. “Only Krick could tell us the weather three or four weeks down the road.”

The Nashville, Tenn., Gas Co. anticipates fuel shortages based on Krick’s winter predictions. “We feel he’s the best there is,” said Les Enoch, senior vice president of the utility. “The local weatherman sure has more trouble than Krick and company.”

In fact, Krick’s claims of accuracy have precipitated a rather stormy reaction from fellow meteorologists, most of whom doubt that reliable long-range forecasts are a scientific possibility.

‘You Can’t Work With Him’

“The Weather Bureau used to tell me: ‘Krick is just a quack. You can’t work with him,’ ” said Abell, who has used Krick’s forecasts for 25 years. “But the Weather Bureau can’t even predict more than three days in advance.”

LaCovey, spokesman for the National Weather Service, said he was not familiar with Krick’s work but added that he would advise his colleagues not to comment on the matter. Kenneth Spengler, executive director of the American Meteorological Society in Boston, also refused to comment on Krick’s methods.

Krick, a current member of the American Meteorological Society, said he resigned in 1958 after the group ruled that his unusual techniques were unscientific. Krick rejoined the meteorological society in January because, he said, he had outlived most of his enemies.

“I don’t think you’ll find anyone in the weather establishment who will say anything too positive about Irving Krick,” said Victor Boesen, author of the 1978 book “Storm: Irving Krick vs. the U.S. Weather Bureaucracy.”

“Krick is a maverick,” Boesen said. “Those kind of people are never very popular among the establishment in any field.”

Other meteorologists are “jealous of Irving Krick,” Deering agreed. “That’s the reason they condemn him.”

Problems Began in 1930s

His problems with the weather bureaucracy began in the 1930s, Krick said, when he was fresh out of Caltech with one of the nation’s first degrees in meteorology. He soon went to work in Hollywood, where the Motion Picture Producers Assn. saw great value in precision forecasting. One of Krick’s first assignments was to pick the night for the burning of Atlanta in “Gone With the Wind.”

As word of Krick’s ability spread, so did the skepticism with which the forecasting industry greeted him.

“Some of the things he’s done have not set well with his colleagues,” said Henry Houghton, professor emeritus of meteorology at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “There are very few, if any, meteorologists who are interested in Dr. Krick’s work.”

But Krick was not deterred. As head of meteorology at Caltech, he developed the basis of his long-range forecasting system by classifying weather patterns for most of the Northern Hemisphere.

During World War II, Krick, a colonel, used that knowledge to provide weather forecasts for the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe. In June, 1944, as one of six consultants to Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Krick said that he and his Caltech staff prepared forecasts for the invasion of Normandy and subsequently for all Allied air and ground forces in Europe.

However, a historian at the University of New Orleans and author of “Eisenhower” said that Krick’s claims are exaggerated. According to Steven Ambrose, it was Group-Capt. James Stagg of the Royal Air Force who forecast the D-Day weather for Ike.

‘Stagg . . . the Most Important’

“Ike told me that when Stagg made the prediction he was the most important man in the Allied world,” Ambrose said.

But records kept by Krick and other forecasters indicate that Stagg collapsed under pressure several days before the invasion, Boesen writes in “Storm.”

“Stagg at one point broke down,” he said. “Ike’s decision to invade was based on Krick’s forecast.”

Despite the controversy surrounding his role in the war, Krick was honored by a group of U.S. military forecasters last summer on the 40th anniversary of D-Day for his role in the invasion.

“We wanted to recognize his selfless contributions and the hardships and agony he has suffered over the years from his contemporaries,” said June Bacon Bercey, chairwoman of the Northern California chapter of the American Meteorological Society and coordinator of the ceremony honoring Krick.

After the war, Krick said he again aroused controversy among forecasters by initiating the world’s first commercial “cloud-seeding” program. He claims that the procedure, which in 1957 was certified as effective by the President’s Committee on Weather Modification, can increase precipitation by 10% to 25% of what would have occurred naturally.

Silver Iodide Particles Released

The release of small silver iodide particles into the atmosphere, Krick said, can increase river flows for hydroelectric projects or reduce hail damage in agricultural areas. As “weather engineer” for the 1960 Winter Olympics, Krick said that he generated seven feet of snow through cloud-seeding after he predicted a potentially dry spell several weeks before the Games.

“Nobody else thought it could be done,” he said. “They still keep knocking it as voodoo.”

Krick has continued to perform cloud-seeding around the world, claiming that he has made it rain in Spain--as well as in France, Italy, Canada and Israel. The 1977 California drought also could have been prevented through weather modification, Krick says, noting that he performed similar measures for farmers in Oklahoma during many of the parched years there.

“About 1970, Krick called one day and said there would be an extreme drought over the next 10 years,” said Deering, who coordinated many of Krick’s cloud-seeding projects in Oklahoma. “I was skeptical at first, but I’ve seen it work.”

After nearly 50 years of predicting what others said was the unpredictable, Krick prides himself on what he describes as “a partnership with nature.”

When Abell asked Krick this spring to select a suitable date for Lady Bird Johnson’s fall picnic in Virginia, Krick picked Sept. 29, just one day after Hurricane Gloria swept through the Northeast.

“Some people here said we should consider canceling the picnic because the hurricane was coming,” Abell said. “But I told them, ‘No, Krick said the day would be lovely.’ In the end, we stuck by our guns and it was beautiful.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.