Voyager 2 Detects Uranus Radio Waves

- Share via

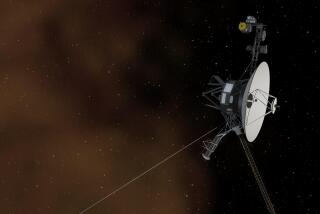

Voyager 2, speeding toward its closest encounter with Uranus this morning, has detected bursts of natural radio waves emitted by the gaseous planet, giving scientists a valuable new tool to help unlock its secrets.

The spacecraft, which will pass within about 50,000 miles of Uranus’s cloud tops at exactly 50 seconds past 9:58 a.m. today, picked up the first burst of natural radiation on Monday, scientists at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena said Thursday.

They said subsequent bursts confirmed the finding, which proves that Uranus has a magnetic field. Such a field should help provide more knowledge about the nature of Uranus and its origins.

The magnetic field, according to Voyager’s chief scientist, Edward Stone, should tell scientists much about what will be hidden from Voyager’s cameras as it speeds past the cloudy planet at more than 40,000 m.p.h.

A magnetic field means that Uranus, like Earth, has some form of internal dynamo, indicating either that its center may be molten or that it could be covered by an electrically charged ocean, Stone said.

Scientists should be able to tell which of those is more likely when Voyager’s instruments reveal the strength of the field.

“Once we know how strong it is, one can begin to understand where it (the magnetic field) was generated,” said Stone, who is chairman of the Caltech physics department.

A magnetic field means that the planet is rotating and that there must be an internal energy source--either a hot, molten core or, if the field is weak enough, a huge, ionized ocean, Stone said.

The magnetic field should also help scientists determine the length of the Uranian day, because the field rotates with the planet and that rotation should be measurable. Determining the rotation of Uranus could otherwise prove very elusive, because the surface of the planet is hidden by the dense atmosphere, thus obscuring any signposts.

The discovery of the magnetic field was no surprise to Voyager scientists. In fact, they had expected it to show up much sooner than it did. Stone said it appears to be only about one-tenth as strong as the Earth’s magnetic field.

The discovery of the magnetic field came amid a continuing flow of images and data from the spacecraft.

Meteor Impacts

The latest photos of the Uranian moons reveal what appear to be cratered surfaces--apparently caused by meteor impacts--but scientists were frustrated in their effort to pick out surface details.

They remain perplexed over why the moons are so dim. The Uranian moons are believed to contain water ice, and that should make them highly reflective.

“If this is water ice, there obviously is something very dark lying on the surface,” said Brad Smith, chief of Voyager’s imaging team.

The mood at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory was one of restless anticipation Thursday, as scientists waited for their first close-up look at Uranus and its moons.

The last set of instructions were to be transmitted to the spacecraft at about 1 a.m. today.

Although it took eight years and a 3-billion-mile odyssey to get there, Voyager will arrive at its closest approach to the planet exactly one minute and nine seconds early.