Iceberg Hunters’ Wreath Honors Victims of Titanic

- Share via

OVER THE NORTH ATLANTIC — The huge plane’s rear cargo doors whooshed open as the navigator somberly chanted the falling altitude: 8,000 feet . . . 5,000 . . . 2,000 . . .

“Drop, drop, drop,” he suddenly crackled on the intercom.

Out sailed a red-ribboned wreath of yellow carnations and white daisies, twisting and tumbling through the gray clouds and splashing into the white-capped sea far below.

“Unto these lost souls of the R.M.S. Titanic,” engineer Dan W. Malott began in reading a eulogy to the whipping winds.

Thus did the International Ice Patrol, one of the least known and most important U.S. Coast Guard operations, pay its annual tribute Friday to the memory and grave site of the Titanic, which sank in one of the best known and most horrific ship disasters.

The salute was only fitting. It was 74 years ago this week when the fabled British luxury liner hit an iceberg and sank about 300 miles southeast of Newfoundland, taking more than 1,500 lives. Last September, U.S. and French scientists found and photographed the ghostly wreck 2 1/2 miles below. They plan to return this summer with small manned submarines.

Shortly after the 1912 disaster, 13 anxious shipping nations met in London to create the International Ice Patrol. Its mission ever since: to search for roving icebergs and warn ships in the busy North Atlantic shipping lanes.

Today, 20 nations share the $2.5-million annual tab for the patrol to carefully chart the icebergs that break off from West Greenland’s massive glaciers and drift into Newfoundland’s Grand Banks each spring and summer. Their ice warnings are broadcast twice a day.

Save Fuel, Lives

“We help mariners avoid the ice,” said Cmdr. Norman C. Edwards, 40, who heads the 16-member ice patrol from computer-crammed, cinder-block offices in Groton, Conn. “We save fuel, time and lives.”

It is no idle boast. In 1984, the patrol’s hardy HC-130 plane tracked a record 2,202 icebergs between March and August. That year, more than 500 ships safely crossed the stormy North Atlantic, carrying 135 million tons of cargo.

Few ships since have shared the Titanic’s fate, but in January, 1959, the Danish ferry Hans Hedtoft sailed through iceberg-infested waters off Greenland and sank with all 95 aboard.

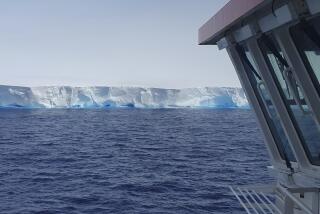

The dangers are obvious. In the parlance of the patrol, icy piano-sized “growlers” lurk in high waves. House-sized “bergy bits” are common. Hulking giants may loom as large as aircraft carriers, with sculpted blue-ice pinnacles soaring 500 feet high.

Of course, those are the just the tips of the iceberg--nearly 90% of any berg’s bulk hides below water. The weather, at least, is steady: “Fog, fog and worse fog,” said ice observer David Hutchinson, 25.

No Collisions

But the ice patrol is “batting 1.000” in another way, said Lt. Neal Thayer, 31. “As far as we know, there have been no ships colliding with icebergs outside the limits we patrol,” he said.

Drifting up to 30 miles a day, the odd berg does escape the patrol’s half-million-square-mile search area. One errant berg is now somewhere off Boston. Another was sighted last week on the same latitude as Bermuda.

“There’s still a lot about icebergs we don’t understand,” Thayer said.

But not for want of trying. Each year, research ships and radio-transmitting buoys measure currents, water and air temperature, wind and waves. Computers analyze the data daily to predict where the bergs are going and when they’ll melt.

Two years ago, the Coast Guard cutter Hornbeam even dogged a football field-sized iceberg for six days to watch it drift and melt down to the 30-yard line.

‘Boring’ Assignment

“Boring,” recalled Keith Pelletier, 28, a four-year patrol veteran. “In fact, very boring.”

It was also useful. The big berg rolled and broke, or “calved,” seven times in five days. Scientists concluded that waves buffeting the berg were more important than warm water or air in causing its eventual breakup.

That doesn’t mean the Coast Guard hasn’t tried to help. Over the years, it has fired deck guns and torpedoes, exploded depth charges and mines, and dropped hot thermite bombs to destroy icebergs. None worked.

“Most of the time, we just got crushed ice,” said Edwards. “They were successful once in splitting an iceberg. But then we just had two bergs to worry about.”

More recently, oil companies with drilling platforms in the Hibernia Field, about 200 miles offshore, have used large tugboats to nudge small bergs out of harm’s way. “If it’s too large, of course, they move the rig,” said Oceanographer Don Murphy.

Icebergs this year are relatively rare. The daily flights every other week from Gander, Newfoundland, tracked only 48 icebergs two weeks ago, compared to about 290 the same time a year ago.

Cancellations, Delays

It’s probably just as well. Wednesday’s flight quickly returned for an emergency landing after an overheated duct burned insulation in the cargo bay. It flew safely again later. But dense fog and snow grounded Thursday’s flight altogether. Friday’s patrol was delayed until a spare part could be flown up from North Carolina.

Once aloft, the patrol flew seven hours to and fro across a Pennsylvania-sized section of ocean. Powerful side-scanning radar called SLAR searched a 54-mile-wide swath 8,000 feet below.

“We got a small to medium berg about eight or nine miles off,” said SLAR operator Chris Adams, circling a tiny fuzzy dot on the radar film with a blue pen. Fishing boats and steamers appeared as more distinct dots. Heavy clouds hid the bergs from view all day, however.

Following ice patrol rules, each iceberg is assigned a number. But lonely ice patrol members sometimes use more descriptive names for their strangely shaped, elusive icy quarry.

“We had one once we called Miss August,” said Pelletier with a laugh. “And last year, we had the Playboy Bunny berg. It only took a little imagination.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.