Cells Take on New Idenity, Ward Off Antibiotics : Jumping Genes Help Bacteria Survive

- Share via

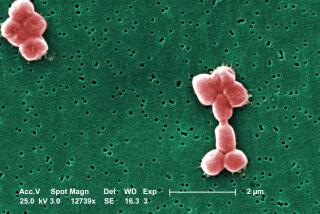

Molecular warlords waging a microscopic battle for survival may be the reason why people with gonorrhea no longer respond to penicillin.

Scientists at the University of Southern California looking into the phenomenon of jumping genes say a chemical battle is being fought by the genes of bacteria that defend themselves against antibiotics.

The problem is of particular concern to doctors treating hospitalized people who require extensive antibiotic therapy for a wide variety of diseases brought on by bacterial infections.

Apparently, some bacteria with special enzymes can resist the killing power of an antibiotic by manufacturing a gene-blueprint for a specific enzyme and dispatching those copies to fellow bacteria.

Armed for Survival

Those blueprints are then moved from cell to cell arming the bacteria for survival.

“The term jumping gene is the popular expression for something called transposable genetic elements,” molecular biologist David Galas said, describing the capability of entire segments of DNA to move from one position to another on a chromosome.

The phenomenon of gene mobility, first discovered in corn in the 1940s by New York geneticist and Nobel laureate Barbara McClintock, is the reason why cells can take on new identities.

“Among bacteria there is a microscopic war going on at all times,” Galas explained. “We see this all the time in the bacteria of soil.”

Because the bacteria are more or less fighting for survival, they continue producing enzymes that destroy their enemies.

“The biggest danger occurs in environments where people are constantly exposed to infections,” Galas said.

Hospitals Likely Sources

He cited hospitals as one of the most likely sources of infections by drug-resistant bacteria.

“The fascinating thing about jumping genes is that they move onto things called plasmids in a cell, and that’s what gives them the mobility to move from one cell to another. In that sense, they are a lot like a virus.

“Sometimes there are plasmids in wild bacteria that are packed full of genes that code for resistance to certain antibiotics, primarily the tetracyclines and penicillin,” Galas explained.

He said some airborne bacteria acquire antibiotic-resistance in mid-flight as the plasmids literally “hitchhike from cell to cell.”

Close-Contact Transmission

Other drug-resistant bacteria are transmitted by close contact between people as in the case of gonorrhea, Galas said, emphasizing that most strains of gonorrhea now carry the plasmids that ward off attack by certain antibiotic drugs.

“The Third World is a major area of concern because people in many of these countries can buy almost any antibiotic over the counter.

“Whenever people don’t feel well, they just go out and buy a strong antibiotic, which they take without regard to dosage. Drugs like that would require a prescription here in the United States.

“This sets up a situation in which stronger and stronger antibiotics are required to fight even the simplest infections,” Galas explained.

He said the most dreadful prospect of jumping genes is the possibility of rendering resistant to attack those bacteria once thought conquered by antibiotic drugs.