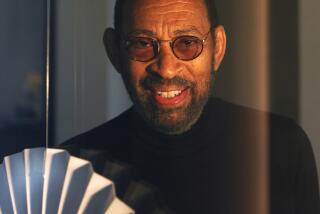

John Bubbles, Tap-Dance Great, Gershwin Performer, Dies at 84

- Share via

John W. Bubbles, the father of rhythm tap-dancing and George Gershwin’s personal choice as the original Sportin’ Life in his American operatic classic “Porgy and Bess,” died Sunday night at his Baldwin Hills home.

The star of vaudeville, the Ziegfeld Follies, stage, screen and television was 84 and had been semi-retired since a 1967 stroke left him partially paralyzed.

In 1919 the lanky black theater usher and bowling alley attendant and his teen-age pal Ford Washington became Buck and Bubbles, perhaps vaudeville’s best-known dance and patter team. They were boys working at odd jobs in Louisville, Ky., when the shuffles and piano routines they had polished in their off hours won them a spot at the Kentucky State Fair. That performance and a subsequent appearance at the Mary Anderson Theater in Louisville brought an offer from the Kiss Me Company, one of vaudeville’s touring troupes.

Within a year they were playing the Palace in New York, mecca for the odd assortment of actors, comics, acrobats, singers and dancers who comprised vaudeville and provided Americans with the thrust of their live entertainment through World War I and the Great Depression.

Bubbles, born John Sublett, made a singular and lasting contribution to dance when he took the toe-oriented routines then dominating the world of tap, and literally lowered them the length of his foot.

He had been laughed out of Harlem’s fabled Hoofer’s Club for what his contemporaries said was “hurtin’ the floor.” After that affront, he worked up a style that he came to call rhythm tap in which he minimized the body movement in tap-dancing and used both his heels and toes to produce accented syncopations. He also slowed the frenetic tempo of tap so that audiences could hear the nuances he coaxed from his feet.

“I’d just listen to the music and feel what I could do with it,” Bubbles said in a long-ago interview with The Times. “Then I’d put it together in my head. When I figure I’ve got it, I get up and do it. Then it’s all synchronized together.”

Big-Name Players

In the 1975 book “The Vaudevillians,” Bubbles recalled that his dancing and Buck’s stand-up piano antics (he was too short to play while seated) brought them billing at the Palace over George Burns and Gracie Allen and on the same stage with Al Jolson, Eddie Cantor and Kate Smith.

It was not just a professional but a personal triumph, for in that era black performers often had to put cork on their faces and cover their hands so audiences wouldn’t realize they were Negroes.

They were the first black act ever held over at the Palace and the first black act to perform at Radio City Music Hall.

Buck and Bubbles toured America and Europe and came to the attention of Florenz Ziegfeld, who put them in his 1931 Follies. They proved not only dancers who could sing but singers who could do comedy. In a typical bit of patter, Bubbles would tell Buck to pull the piano around the stage and “my end’ll follow.”

They were also earning $800 a week, an unheard of sum for even most white headliners.

Return to Vaudeville

After the Follies, Buck and Bubbles returned to vaudeville for several years until Gershwin heard Bubbles’ untrained but quality voice and asked him to become the boisterous Sportin’ Life in the historic, all-black “Porgy and Bess,” produced in 1935.

Later he made such films as the black musical “Cabin in the Sky” and the musical divertissement “Varsity Show.”

If he came in later years to be less familiar to the public, he remained a legend among his peers and in 1979 was invited to sing at the Newport Jazz Festival in New York.

Buck died in 1955 but Bubbles continued to tour, although now the accent was on his singing and teaching. He showed up regularly at the Variety Arts Center in Los Angeles for various nostalgia nights and in 1967--shortly before the stroke that severely limited his appearances--returned to the scene of Buck and Bubbles’ most significant triumph, the Palace Theater.

“Makes you feel at home to hear that kind of applause,” he said after his performance.

Bubbles is survived by his wife, Wanda, and a sister, Carrie Leacock of Jamaica, N.Y.

Funeral services are pending.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.